Handout: Introduction to Moral Relativism

October 2, 2008

The Nature of Moral Theory

The Nature of Moral Theory

Moral theory asks the questions: what is meant by “good”, what makes a “good action” or a “good character”?

Consider the following statements which all have the word “ought” in them, implying that I am strongly for or against some action.

“You ought not to steal, because it will upset the person you steal from”.

“You ought to steal if you are starving and have no choice”.

Both are moral statements with the word “ought”. Both are about stealing. But they take two different views. Why is this?

Both are reasonable statements because they give grounds for a decision. Both refer to an end in sight: the first example considers the end to be the welfare of the person you are stealing from, and the second, your own welfare, because if you don’t steal, you will die!

We call theories that refer to ends teleological theories, from the Greek telos = end or purpose.

We call theories that refer to duties or rules deontological theories (deon = duty). An example might be the statement: “stealing is always wrong”.

Relative and absolute theories of morality

Below is a diagram showing the essential distinction we make when considering ethical theories, between relative and absolute theories.

We make a distinction between twp types of relativism, and the idea of absolute morality or absolutism.

The basic issue in question is whether there is such a thing as objective values, which hold for everyone, everywhere, irrespective of time or culture, such as the value in the statement genocide is wrong.

(Fig 1)

A relative theory can be of two types.

Cultural relativism is simply the observation when we look at different cultures that they have different views of right and wrong. We are not giving reasons for this difference, nor are we judging the cultures. We are just observing them. As one writer observed in 1934:

“Morality …is a convenient term for socially-approved habits” (Benedict: 1934).

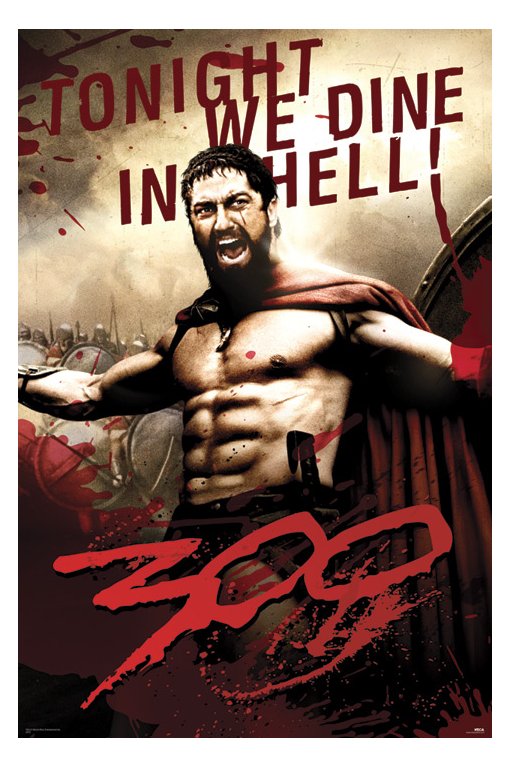

For example, consider Spartan culture. Sparta was a warrior state which thrived in the second and third centuries BC, and was well illustrated by the film the 300 which told the story of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC when 300 Spartans held a pass against the huge Persian army until betrayed by a shepherd who showed the Persians a secret way through the mountains.

For example, consider Spartan culture. Sparta was a warrior state which thrived in the second and third centuries BC, and was well illustrated by the film the 300 which told the story of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC when 300 Spartans held a pass against the huge Persian army until betrayed by a shepherd who showed the Persians a secret way through the mountains.

The end or telos of Spartan culture was to produce a strong warrior race in order to survive in the cut-throat world of Greek city states.

Here are some of the ways they produced this virtue of heroism.

• Infanticide weak male babies were left to die on the hillside and weak female babies were thrown off a cliff.

• Childen’s education was taken over by the state at the age of 7, when boys were forced into the wilderness to fend for themselves.

• Slavery the Spartans enslaved the Macedonian people, who had no rights. Indeed, to prove yourself a warrior it was enough to kill a Macedonian in cold blood.

Film Extract Exercise:

Summarise the way of life of the Spartans from this extract from the film, the 300.

James Rachels’ argument

James Rachels argues that we make a false inference when we say:

James Rachels argues that we make a false inference when we say:

1. Different cultures have different moral codes.

2. Therefore there is no objective truth.

The false inference lies in the “therefore”. Both appear to be statements of fact.

But statement (2) is actually a belief. We cannot prove the case that there is no objective morality, and it doesn’t follow from the observation that there are different moral systems in the world.

After all, we can have different belief systems (as a matter of fact) about whether the world is round or flat, but it doesn’t change the truth or falsity of the objective claims of science.

Rachels goes on to consider some consequences of relativism:

• We can’t judge other societies (such as Hitler’s Germany)

• We could in principle take a vote on slavery and judge its rightness by a simple majority decision.

• We can’t judge our own society and find, for example, fast driving “wrong”.

• Moral progress is called into doubt, where we seem to have new laws protecting human rights, for example.

Rachels concludes that:

“It makes sense to think that our own society has made some moral progress, while admitting that it is still imperfect and in need of reform” (Rachels page 23).

Rachels goes on to argue that differences in moral codes stem from differences in beliefs.

If we go to India we may be surprised to find it’s wrong to eat a cow, but this is because cows have divine status in India, so relativism is correct in so far as it reminds us that morality is relative to belief systems. Yet relativism is wrong if it claims to establish that we cannot judge some practices as universally desirable and others undesirable.

For example, all cultures protect their young, otherwise we would not survive. Similarly, truth-telling is universally accepted, because trust is necessary for survival.

What relativism helps us to see, however, is that all values have some reasonable basis, and it is our task to find the reasonable basis for moral statements and establish the reasonable grounds for saying, for example, that killing is wrong.

And we must be humble about our own culture which may contain practices which we should seek to reform, where progress is still required.

The nature of normative relativism

J.L.Mackie argues in his book Inventing Right and Wrong that there are no objective moral values, even though, as William James observed, many of us are “absolutists by instinct”.

J.L.Mackie argues in his book Inventing Right and Wrong that there are no objective moral values, even though, as William James observed, many of us are “absolutists by instinct”.

Mackie argues that the claim to objectivity is stronger than just a claim to adopt the same “methods of ethics”, as Henry Sidgwick called the shared approach to ethical reasoning. It is a commitment to ideals.

These ideals are deeply held beliefs about the nature of the world, ourselves, and the right or wrong course of action. R.M. Hare called this “fanaticism” because very little can shake us from these deeply held beliefs, except perhaps some trauma, such as the slaughter of the First World War or the horror of the Holocaust.

Mackie concludes that:

“A belief in objective moral values is built into ordinary moral thought and language, but holding this ingrained belief is false” (Mackie, 1977:49).

Mackie claims it is possible to show how people persist in these false claims. This is because morality depends on what Mackie calls “forms of life”. The way we live, the patterns of behaviour adopted by our culture determine our views of right and wrong. It is not our views of right and wrong which determine our culture.

For example, even though there are plenty of verses in the Bible which, in principle, could be used to establish the equality of men and women (Galatians 3:28 “there is neither Jew nor Greek, male nor female, slave nor free, but all are one in Christ Jesus”), nonetheless, it took the two world wars, the rise in women’s employment in times of crisis, to show that women really could do the jobs men do.

So a change in form of life, the employment of women in factories to aid the war effort, came before a change in moral thinking, that the inequality in job opportunities between men and women was morally wrong.

Exercise: think of one other example of a change in “form of life” leading to a change in moral thinking. Think, for example of changes in sexual ethics in the last hundred years.

Normative ethics

Normative ethics is the study of the values which underpin views of right and wrong. Normative ethics looks at criteria of reasonableness. What different reasons can people give for saying something is wrong, and are those reasons coherent and logical.

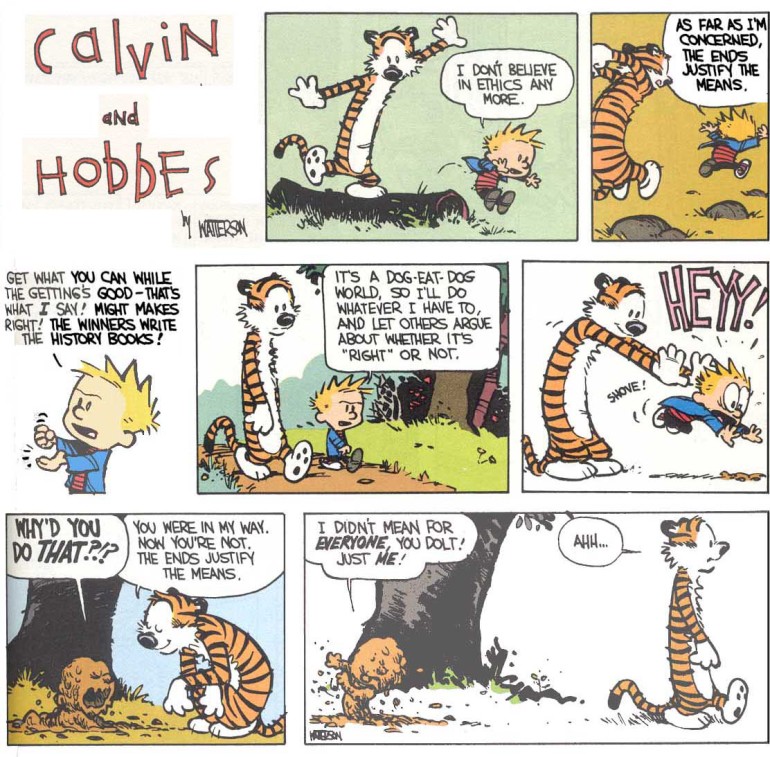

So normative relativism, for example, is the study of why values differ according to different ends or purposes which people may define as “good” or desirable. The idea of goodness is relative to the end or goal we select as desirable.

For example, consider two relativistic theories of morality: situation ethics and utilitarianism. Neither are pure relativism as they have one absolute each, that of love and happiness, which is non-negotiable. However, Joseph Fletcher himself (author of Situation Ethics) describes his theory as “relativistic” so perhaps we need a new description of “weak relativism” for these theories, where the realtivism is a. relative to the end in view and b. because the idea of happiness or love is somewhat vague, this end itself will be highly culturally determined.

In situation ethics the end (Greek: telos) is love, a special form of love (agape or commitment love).

In situation ethics the end (Greek: telos) is love, a special form of love (agape or commitment love).

In utilitarianism the end or purpose is the maximising of happiness or pleasure (depending on the type of utilitarianism).

So if a family is considering the ethical question, should a 16 year old girl have an abortion, the situation ethicist will ask the question, what course of action will produce the most loving outcome? They would tend to look at the individual first, so the daughter’s interests would be paramount here. If the decision was to keep the child, then the family might find ways of giving the girl maximum support and love.

A utilitarian would look at the overall happiness of the daughter and her wider family.

If the society around them found illegitimacy unacceptable, then the family might argue that the daughter, the community and her family’s happiness would be maximised by having an abortion. The place of the unborn child would depend on another argument: whether a foetus should be given the status of a person. If the answer was “yes, it should” then we should consider the future happiness of the unborn child as well in our moral calculation.

Both situation ethics and utilitarianism are relativistic, “weak relativism”, as discussed above. But the values they make goodness relative to, agape love and happiness respectively are different. So moral relativism can produce very different outcomes depending on the different goals or ends in view which are felt to be desirable.

Exercise: sum up the way in which situation ethics and utilitarianism are relative theories.

In situation ethics, goodness is made relative to………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

In utilitarianism, goodness is made relative to …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Do these two values necessarily produce the same outcome for identical facts of the case?

In your own words, sum up what is meant by ethical relativism.

In your own words, sum up what is meant by normative relativism

Absolute theories of ethics

Absolute theories of ethics establish rules or duties which must always be followed, irrespective of the circumstances.

For example, some people have argued that the ten commandments in Exodus 20 are absolute rules which must always be obeyed, because they come from God.

There is a problem with this argument, however. Even in the Old Testament it seems God himself commands people to kill. For example, Joshua is commanded to destroy Jericho and its inhabitants and also annihilates the people of the city of Ai (Joshua 8), not even sparing the children.

There is a problem with this argument, however. Even in the Old Testament it seems God himself commands people to kill. For example, Joshua is commanded to destroy Jericho and its inhabitants and also annihilates the people of the city of Ai (Joshua 8), not even sparing the children.

“Then they killed all in the city, both men and women, young and old, oxen, sheep and donkeys” (Joshua 6:21)

If we argue that killing is absolutely wrong, how to we explain these apparent acts of murder (killing of the innocent children) as supposedly commanded by God himself? When does killing in war become justified?

There is a further difficulty. In court we distinguish between different degrees of murder. First degree murder is when someone kills in cold blood, for example, shooting a policeman to make good an escape.

Second and third degrees of murder have extenuating circumstances. For example, killing someone in a fit of anger because you discover they have lied or cheated on you. Then there is killing is self-defence, or shooting a burglar who you find in your house. We tend to treat the latter as manslaughter, and in law it takes a lesser penalty and sometimes, no penalty at all.

So to say “thou shalt not kill” is an absolute, even if we translate “kill” as “murder” doesn’t escape the problem, “what sort of killing is acceptable”?

As soon as we admit exceptions, or particular circumstances when we would kill, we become a relativist, because we make goodness relative to some other end, such as saving a life or preventing a bigger evil.

Deontological theories

The word deontos comes from the Greek word meaning “duty”. Duties and rules tend to be non-negotiable. For example, Kant establishes his theory of ethics on something he calls the categorical imperative.

With a relativistic statement, we present a conditional, if…then clause. The purpose of this clause is to try and establish the circumstances under which we might do or not do something.

“If you are hungry, then it’s acceptable to steal”.

“If you are defending yourself, it’s ok to kill”.

However, a duty tends to be expressed categorically with no “ifs”.

“You ought to defend the young”.

“Society should make provision for the elderly”.

Neither of these two statement say anything about the circumstances under which these things, the defending of the young, and providing for the elderly, should take place. The two statements are statements establishing duties.

Later we will consider how Kant derives his theory of duty and obedience to what he calls “the moral law”.

Natural Law is another form of theory which establishes rules for conduct based on what is observable as the natural function of something. For example the Roman Catholic Church has argued in documents like Humanae Vitae (available on the website philosophicalinvestigations.co.uk) that the natural function of sex is reproduction, and that anything that interferes with this natural function is wrong.

For example, contraception interferes with this natural function of sex, according to the catholic view, and so is a serious sin. The Catholic view as expressed by Humanae Vitae is that the use of contraception (and abortion) is an offence against God because it removes the potential for life and interferes with this natural process of conception.

So we have a law or rule, “the use of contraception is wrong” and there are no circumstances considered in which this rule can be broken.

Exercise: Do you agree with the Natural Law view of contraception? If you disagree, what argument can you think of that might oppose this view?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

………………………………………………………………………………………………

Now try this self-marking multiple choice by pressing this link:

Lawrence Hinman of San Diego University has produced an excellent, thought-provoking powerpoint arguing for a middle way between relativism and absolutism, which he calls “pluralism” – a way of doing ethics in a multicultural world.

http://ethics.sandiego.edu/presentations/Theory/Relativism/index.asp

Reading

Level 1 readings (from my bibliography)

Bowie (2004) chapter 1

Mackie (1977) chapter 3

Rachels (1998) chapter 5

David Wong in Singer ed (1994) chapter 39

Humanae Vitae (1967)

Level 2 readings (from Bristol University degree course)

Moral relativism is a form of moral scepticism (see Moral Scepticism) as relativists deny that there are universal moral truths. They do not deny that there are moral truths, they merely insist that moral truths are relative to particular perspectives (e.g., a culture). The most common argument advanced for moral relativism appeals to the variability of moral codes and practices. The difficulty, however, is explaining how these descriptive facts support relativism as variability of belief holds in other domains (e.g., science) where relativism seems less plausible. Nor is it as easy as the relativist may think to support the descriptive claims. Many make mistaken normative inferences from the purported truth of moral relativism-such as that the truth of moral relativism supports toleration of other cultures and ways of life (if the relativist is right, then toleration is just another value which is relative like any other).

Plato, Protagoras

R. Benedict, Patterns of Culture

J. Ladd (ed.), Ethical Relativism

D. Wong, Moral Relativity

G. Harman, ‘Moral Relativism Defended’, Philosophical Review (1975)

G. Harman, ‘Is There a Single True Morality’ in D. Copp. and M. Zimmerman (eds.), Morality, Reason, and Truth

G. Harman and J.J. Thomson, Moral Relativism and Moral Objectivity

B. Williams, Morality

B. Williams, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy, chapter 10

H. Putnam, ‘Bernard Williams and the Absolute Conception of the World’ in Renewing Philosophy

Exercises

1. Evaluate these extracts from a number of sources.

“The general retort to relativism is simple, because most relativists contradict their thesis in the very act of stating it. Take the case of relativism with respect to morality: moral relativists generally believe that all cultural practices should be respected on their own terms, that the practitioners of the various barbarisms that persist around the globe cannot be judged by the standards of the West, nor can the people of the past be judged by the standards of the present. And yet, implicit in this approach to morality lurks a claim that is not relative but absolute. Most moral relativists believe that tolerance of cultural diversity is better, in some important sense, than outright bigotry. This may be perfectly reasonable, of course, but it amounts to an overarching claim about how all human beings should live. Moral relativism, when used as a rationale for tolerance of diversity, is self-contradictory.”

Sam Harris, The End of Faith (Page 179, The Demon of Relativism)

“It is the source of squirming internal conflict in the minds of nice liberal people who, on the one hand, cannot bear suffering and cruelty, but on the other hand have been trained by postmodernists and relativists to respect other cultures no less than their own. Female circumcision is undoubtedly hideously painful, it sabotages sexual pleasure in women (indeed, this is probably its underlying purpose), and one half of the decent liberal mind wants to abolish the practice. The other half, however, ‘respects’ ethnic cultures and feels that we should not interfere if ‘they’ want to mutilate ‘their’ girls.”

Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (Pages 328-9, Childhood Abuse and Religion)

“The more one learns of the different passionately held convictions of peoples around the world, the more tempting it becomes to decide that there really couldn’t be a standpoint from which truly universal moral judgments could be constructed and defended. So it is not surprising that cultural anthropologists tend to take one variety of moral relativism or another as one of their enabling assumptions. Moral relativism is also rampant in other groves of academia, but not all. It is decidedly a minority position among ethicists and other philosophers, for example, and it is by no means a necessary presupposition of scientific open-mindedness. We don’t have to assume that there are no moral truths in order to study other cultures fairly and objectively; we just have to set aside, for the time being, the assumption that we already know what they are.”

Daniel C. Dennett, Breaking The Spell (Pages 375-6, Some More Questions About Science)

0 Comments