Handout: Kantian Ethics – PMB introduction

August 27, 2008

Introduction

Introduction

This handout is a summary of a more detailed treatment in my book Kant and Natural Law, which contains longer extracts from key authors. I recommend that you purchase the book if you are aiming for A grade. PB

Roger Scruton calls Kantian Ethics “one of the most beautiful creations that the human mind has ever devised” (1996:284). Kant believed that when I say “killing is wrong”, I imply “everyone ought not to kill”, and this is a universal good which applies to all rational beings.

However Kant also believed that a moral principle could be generated a priori, which means “before experience”. This means the idea of “goodness” is independent of someone’s needs or desires, which can only be known a posteriori , “after experience”.

Kant’s great project was to prove that reason alone can generate a moral principle such as “thou shalt not kill”, whose validity is not subjective, but objective (valid for all people everywhere and at any time).

For this morality is built on practical reason alone, and nothing else: a type of reasoning which is very different from scientific reasoning, for example, which he calls “pure reason”, because practical reason belongs purely to the realm of ideas.

The Logic of Kantian Ethics

Kant’s argument has a faultless logic that starts with the idea of human autonomy (freedom or self-rule). There are a number of steps he takes to establish the idea of what is good and bad.

- We are free (autonomous or self-ruled).

- This freedom means we can choose to act from reason alone, overuling desires and emotions.

- The form of reason used is a priori reasoning, that doesn’t depend on desires or feelings, but only on abstract reasoning, like mathematics. This is then applied to the real world of experience (the truth is syn thetic, meaning true by expereince, not analytic, meaning true by definition).

- The only thing good in itself is the good will, because any other motive for acting, such as happiness or pleasure is corrupted by desire and emotion, which are fickle things, subject to change and circumstance.

- So the only moral act is one from duty alone, using reason to work out what is right and wrong.

- The a priori principle all rational people will come up with is called the Categorical Imperative which means “an unconditional command”.

- This imperative has three forms, the principle of law, the principle of ends, and the principle of autonomy.

- The principle of law says we should universalise our actions and turn them into a universal law, so that what I believe is wrong is also wrong for everyone else.

- The principle of ends universalises our humanity and says: treat everyone as if they had the same dignity and freedom as you do.

- The principle of autonomy asks us to imagine we are the sole ruler. What laws would we come up with that could be applied to everyone, irrespective of gender, colour, financial situation etc.?

- So we have our absolute principle (the categorical imperative) which we can apply to the real (synthetic) world to generate rules of conduct and ideas of moral goodness.

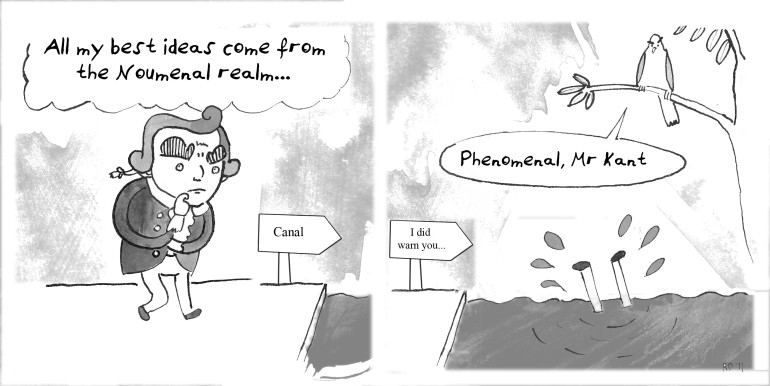

- These form part of the objective moral law, although they don’t belong to the world of things (the phenomenal world), but the world of ideas (the noumenal world), where categories like cause and effect, space and time exist.

Two inspirations: Newton and Rousseau

Two inspirations: Newton and Rousseau

Kant was inspired by Isaac Newton to look for a rational revolution in ethics, and by Rousseau to put equality, dignity and absolute respect for human beings at the heart of his theory.

The eighteenth century was a period of philosophy when Natural Law was dominant. Natural Law held that morality derived from the nature of the world and of human beings. Human beings had a function, to exercise reason, but they exercised this reason very much in line with the principles of science: they made deductions from observation and proceeded a posteriori (from experience).

How might this work?

I observe that human beings are social animals who also seem to abide by certain rules in ordering the conduct of the group. It seems important to them to maximize the happiness and welfare of the group, and protect itself from harm, danger and pain, or anything that upsets group harmony and coexistence.

From this we can observe certain naturalistic features of morality, features of the natural world. For example, we observe features of human beings and their minds, such as the presence of guilt and shame which deters some behaviours, and the response to praise which reinforces others.

So we can produce a list of things which are good, generated by the role of human beings exercising their choices in order to realise the value of the happiness and welfare of the group ( and so in sense defining these things as “good” or “desirable”).

Natural Law theorists might differ as to what is on the list. For example, Aristotle’s list might be different from Aquinas’ list, partly because Aquinas was a Christian who believed that the reasonable person would always end up agreeing with the view of God found in the Bible, who is the source of reason and sets the standard for reasonableness.

But it is the method which is important here: proceeding from observation to inferences about what constitutes the good: an a posteriori way of reasoning dependent on the real world of our senses.

Kant’s answer to Natural Law

Kant’s answer to Natural Law

So when Kant writes:“Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration….the starry heavens above me and the moral law within” he is paying tribute to two approaches to reasoning, the pure scientific reason and the a priori practical reason.

The starry heavens are a tribute to Newton and the advances in scientific discovery using the scientific method of observing things and then working out laws from this process. If Newton can do this using pure reason operatinga posteriori, from experience, couldn’t Kant fulfil a similar purpose using practical reason operating a priori? Couldn’t he provide a groundwork to the metaphysics of morals, where metaphysics means beyond physics, just as Newton had produced a groundwork to the physics of science? As we have noted, the approaches are essentially different, and reason uses a different method with each (or so Kant set out to prove).

The Church with its use of threats of damnation, inquisitions, and influence on law had restricted the free exercise of reason. So although Kant may have believed that some afterlife exists which ultimately rewarded duty, his philosophy was against the oppressive nature of the Church and very much for the free exercise of reason. We are all moral legislators for our own lives, argued Kant, and in so arguing he is the precursor of the great libertarians of the eighteenth century, like J.S.Mill.

Kant’s first inspiration was Newton, because Newton showed how reason unleashed could transform our understanding. Kant’s second great inspiration was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who had famously declared “all men are born free, but are everywhere in chains”. What Rousseau applied to the political sphere (equality and freedom around a common interest) Kant applied to the moral sphere.

Kant’s starting point is freedom

Here we encounter Kant’s starting point, that we are autonomous moral beings. Autonomous means “self-ruled” and its opposite is heteronomous or “other-ruled”. Kant argued that we needed a way of producing moral principles (he called them “maxims”) which did not imply we were ruled by another, but were self-ruled (autonomous). The two heteronomous forces on us, Kant argued, were God and our human emotions (what Hume called “the passions”). Kant believed that our emotions pulled us in different ways, and so opposed Hume’s view that “reason is the slave of the passions”.

To Kant it was impossible to be rational and follow our passions. Kant often called these passions “pathological” which implies, as Paul said in Romans 7 “the very thing I do not want, this is what I do”. There is a kind of war on between the irrational passions and the rational will. To Kant there is a “causality of freedom” implied by the idea of rational choice; as Scruton puts it :

“Morality, by presupposing freedom, shows that our freedom is real; all other motives enslave us” (1996:286).

Why Kant opposes emotion

In this way Kant’s imperatives stood against the natural order of emotions. Instead of the argument running like this:

observation —-> natural human nature ——-> idea of goodness

Kant’s argument runs like this: reason ———> universal principle ———–> idea of goodness

So a Kantian imperative does not say “I ought because I want” but rather “one ought because it’s universally right” (the impersonal “one” or “du” in German), and remember “ought implies can” because it is possible in the real world. We do have freedom to choose and power to act.

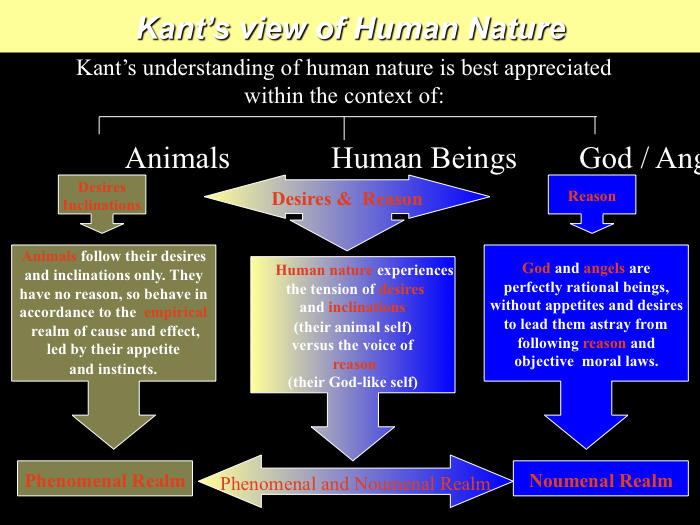

Phenomenal or Noumenal

Kant believed human experience could be divided between two realms, the realm of ideas and the realm of experience, and that morality came from the realm of ideas.

Kant thought that God, angels and human beings shared in the realm of ideas or the noumenal world which was there to be discovered by our reason. The way we look at morality is structured by the human mind, which is able to understand some things a priori, before any use of our five senses, using practical reason. Much of Mathematics, for example, is understood this way, and when Einstein came up with his theory of relativity this too was an a priori concept. He never did the experiments to prove it was true: he left that to the Cambridge scientists.

The second realm is the realm of the observable and of experience, which Kant calls the phenomenal realm. This part of human experience can be felt, touched, seen, smelt, heard. It includes our emotions, too, which Kant continually contrasts with our reason.

Humans access both realms: the noumenal and the phenomenal. But morality takes its absolute authority from the noumenal world, and is derived a priori. It is then proved to be true or false by being applied to the world of experience the synthetic. For example, it only makes sense to say “lying is wrong” when confronted with a situation where I am tempted to lie. I must always follow this rule, however, and so, in a sense, conquer my feelings with the supreme good of duty to follow the moral from the pure motive of the good will. This is what is meant by the synthetic a priori.

To sum up:

The phenomenal world is subject to pure reason imposing order and patterns on what we observea posteriori.

The noumenal world is subject to practical reason imposing order and patterns on what we deduce by a priori abstraction (removing our emotions or desires from the process).

For a level 3 discussion of Kant by two leading philosophers, Geoffrey Warnock and Brian McGee, which explains how “the essential concepts of morality are built into rationality itself” (Geoffrey Warnock) but are in the end noumenal “things-in-themselves”, go to:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VOnQ1fSQ1MQ?rel=0]

The good will and the good agent

Things can have intrinsic good, because they are good in themselves, or instrumental good, becuase they are a means to something else. Kant argued that the only thing intrinsically good was the good will.

Kant argued that the only thing that is good without qualification is the good will. The good will is never instrumental, it doesn’t require a goal or end (such as happiness or love or flourishing). It isn’t a means to something else.

“The good will shines like a jewel for its own sake as something which has full value in itself”. Immanuel Kant

Here Kant may be seeming to push his own moral thinking into a corner. Is he really saying an action is only good if done out of a sense of duty to the moral law? Is the only allowable motive the motive of duty? What if I enjoy helping old ladies across the street, or pay my taxes because of self-interest (I don’t want to incur the £100 fine for not filling in my tax form)? Does that somehow empty my action of any moral worth?

Can my good will somehow be corrupted by desire or emotion, those two outside influences Kant is trying to set us free from (together of course with freedom from the external “God”)?

Here Kant, if we are right in interpreting him this way, is against not just Hume but also Aristotle and the virtue ethicists. For Aristotle a virtuous person needed to really enjoy the pursuit of friendship, honesty, temperance or courage. If he or she didn’t enjoy it, they were not really flourishing, nor were they acting out of their character or ethos.

But are we right to criticize Kant for seeming in places to argue that only an action done out of the motive of duty is morally good? Kenny would argue we are.

“We must distinguish between acting in accordance with duty , and acting from the motive of duty. A grocer who is honest from self-interest…may do actions in accordance with duty. But actions of this kind, however right and amiable, have, according to Kant, no moral worth. Worth of character is shown only when one does good not from inclination, but from duty”. (Kenny, 1998:137)

In a brilliant essay Schneewind (ed. Guyer, 1992:326) argues that this may be a misunderstanding of Kant’s position. What Kant is arguing is that emotion or desire is a wobbly compass by which to steer our choices because love, pity, generosity arethings which depend on the circumstance (or whether I’ve just had a row with the mother-in-law or eaten something dubious for breakfast). Moreover, I can act for example out of pity and do something quite immoral, like let off a hardened criminal who tells me a sob story about how his little dog has just died. The US public rallied behind President Nixon when he was accused of accepting bribes: he went on TV and talked about the gift of a little dog “and you know something? Pat (his wife) really loved that dog”.

In order to guard against this possibility, Kant argues that the only pure good is to act out of respect for the moral law, to act out of duty. Schneewind comments:

“If merit accrues only when we act from a sense of duty, it seems that human relations must either be unduly chilly or else without moral worth. Did Kant really hold this view? There are passages which suggest he did. He rejects the feeling of love as a proper moral motive (Groundwork 4:399 / 67); he usually treats passions and desires as if their aim is always the agent’s own pleasure (Groundwork 4:407/ 75); and at one point he says that the aim of every rational person is to be free from desire (Groundwork 4:428 / 955). In other passages he shows a more humane view (Religion 6:28 / 23; 6:58 / 51). The most plausible alternative to the extreme position is one that allows conditional mixed motives: I may have merit when moved by the motive of pity, say, if I allow pity to operate only on condition that in moving me it leads me to nothing the categorical imperative forbids, and if respect were strong enough to move me were pity to fail” (ed Guyer 1992:328).

Seeking the maxim: the categorical imperative as the groundwork for morality

A categorical imperative is an unconditional command. It is always true, everywhere and for all time. The categorical imperative is the central idea in Kant’s absolute ethics.

Pure reason wills some end (such as happiness) and also some means to achieve that end (such as a being honest, loyal, or fair); it operates using a method much like Newtonian physics (from a fact such as my feelings or desires to a value such as happiness via a means such as being honest).

Practical reason argues Kant “was given to us in order to produce a will which was good not as a means to an end, but good in itself” (Groundwork). So we must test our actions according to a rational process against the standard of the categorical imperative, which is a fixed compass point, like the north pole, which doesn’t change and is derivable a priori. This principle, derived a priori, is then applied synthetically to a real world situation in order to determine what to do.

How can we derive such a principle as the categorical imperative a priori without recourse to arguments from experience, ends (as in Utilitarianism) or emotions (as with Hume’s appeal to our natural sympathy or feeling for one another)?

Kant’s argument proceeds from certain axioms or starting-points, to a conclusion or maxim. The maxim is known as the categorical imperative whose essential feature is universalisability. Below we discuss this maxim in greater detail: here I wish to derive it simply from certain assumptions, grasped intuitively.

Assumption 1: We are perfectly rational agents. The structure of our minds is set up as it were in a certain way. We process our perception of the world by principles of rationality: we see cause and effect and time and purpose in things. We are capable of abstracting from our feelings or even the fear of God. This rationality therefore entails freedom.

Assumption 2: We have freedom of will. We are aware of our freedom intuitively. The desire to follow the moral law within is something we have out of respect for the moral law. We recognize its beauty and validity by intuition (Kant never really proved successfully why we should respect his categorical imperative rather than some other maxim. However, if we accept his two axioms or assumptions, then the the conclusion does seem to follow).

Conclusion: We will reasonably choose to act only through universal maxims, known as the categorical imperative. Kant believed that the summum bonum, a state of affairs where goodness and happiness are achieved, can only follow from people consistently and universally (always and everywhere) acting out of duty (rather than feelings or self-interest or some end such as maximizing happiness). It’s interesting that it is here that God creeps back in, as it were, by the back door, because Kant believed that only in the after-life would a fair distribution of happiness for the virtuous and misery for the selfish be fully achieved.

The categorical imperative (three formulations)

Each way of describing Kant’s categorical imperative has another way of describing it, a test we can apply, and implications to understand. Here we try to examine these.

Kant argues that to be moral we need to act on the categorical imperative which we can work out by practical reason alone. A categorical imperative has no exceptions: it is absolute, meaning it is true for everyone, everywhere, whereas a hypothetical imperative usually contains the word IF, which implies a reason or a feeling or a situation where the hypothetical might apply (If you’re stopped by the Police, don’t swear!). “You shall not lie”, in contrast is an example of a categorical imperative (no reasons given, no circumstances referred to).

A hypothetical imperative usually contains the word IF. This gives a reason, and that reason may be some goal we have (like happiness), some feeling we experience (like compassion or sadness), or a situation we are in (“if you are stopped by the Police, don’t swear!”).

“If you want to be happy, you must be honest” (The hypothetical end here is happiness, the means is honesty) contrasts with the categorical “never lie!”.

“If you want a quiet life, don’t retaliate when someone hits you” (The hypothetical end is a quiet life, the means is to walk away from an attacker) contrasts with the categorical “love your enemies!”.

Kant argues that honesty and non-retaliation, if they are seen to be good, are good absolutely irrespective of my desire or my goal. It is an absolute good but (and this is his key contribution to philosophy, perhaps), it is not unreasonable, unlike the dictates of divine command theory which seem to imply I should obey something because God says so, the only “reasonableness” being that I am afraid I might go to hell or displease God, rather than own the action for myself.

Kant is saying effectively that one ought not to lie, regardless of how you feel about it or how you may be tempted to lie. This is entirely reasonable given the assumptions that lie behind his a priori argument, assumptions of rationality and autonomy (freedom of will). This absolute, unyielding, categorical imperative has three formulations worked out deductively and applied synthetically (to the real world).

1. The Principle of Law: universalise your actions, implying consistency.

“Act only on that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it becomes a universal law”. (1785:80-86)

Practically, we can test our action with a question: “Am I willing that Y should always be followed by everyone in every situation?” The rules which we then generate, such as “no lying” reflect the sacred moral law which can and must have no exceptions. It is absolute and unchanging (like cause and effect or the idea of time). If we apply the principle of law in a particular situation without exception, we have done our duty. We have acted according to duty alone, from the motive of the “good will”.

2. The Principle of Ends: universalise your common humanity, implying equality, that every human agent has absolute worth.

“Act so that you treat humanity, both in your own person and in the person of every other human being, never merely as a means, but always at the same time as an end” (1797:428)

Practically, we can test our action with this question: “Am I treating my neighbour as if I was standing in his or her shoes?”

As Raphael (1981:57) puts it: “to treat a man as an end…is to make his ends your own”.

I take into account before I do something:

- The desires b. The feelings c. The interests of the person or people which are directly affected by my action. I do this whilst ignoring my own desires, feelings and interests.

3. The principle of autonomy: universalise your idea of shared interests, implying that morality is a shared obligation with some idea of a common good.

“Act as if you were, through your maxim a law-making member of a kingdom of ends”. (1797:74)

Practically, we can test our action with this question: “If I was a member of a moral parliament voting according to the national interest, how would I vote?” In other words, I don’t need Parliament, the King, my peer group or God to tell me this. As an autonomous, free individual, I can using my own reason work this out for myself.

And here we are back with Rousseau and his Social Contract, which has recently been developed further by John Rawls in his Theory of Justice. Rawls asks us to imagine we are members of a hypothetical Parliament voting according to two principles of justice:

In this way we can truly argue that Kantian morality has political implications, and we can see how Kant and Rousseau (with his social contract and general will) walk hand in hand. As Raphael (1994:57) puts it:

“It will be seen that the Kantian theory of ethics, like the utilitarian, has political implications. Kantian ethics is in fact the ethics of democracy. It requires liberty (allow everyone to decide for himself), equality (because it requires us to recognize that every human being equally has the power to make moral decisions) and fraternity (think of yourself as a member of a moral community)”. DD Raphael puts it this way in his excellent Introduction to Ethics:

“Kantian ethics is in fact the ethics of democracy” D.D. Raphael

This, then, is a priori reasoning by the free moral agent, which entails a kind of freedom and dignity for all irrespective of education, class or colour. No wonder Kant is described as producing a kind of Copernican revolution, and Alasdair MacIntyre writes: “For many of us who have never heard of philosophy, let alone Kant, morality is roughly what Kant said it was”. (Raphael, 1987:90)

Activity: To what extent is Kantian ethics compatible with Christianity?

What makes a bad act bad?

This section is based on a short article by Sandra Lafavehttp://instruct.westvalley.edu/lafave/Kant_eth.htm

Pure reason finds two ways of determining whether an action is bad: a contradiction in will and a contradiction in nature.

Kant analyzes evil as a kind of logical error, or mistake in reasoning. A contradiction is the worst logical error. It would obviously be a contradiction for a rational being to say “Every rational being should do X, except me.” Contradiction of this form is called special pleading. When rational beings will to do bad things, they want a contradiction: they want everybody else to do the right thing, because that’s exactly what makes their wrongdoing possible. For example, the liar wants everyone else to tell the truth; if everyone lied, no one would believe the liar’s lie. So the liar in effect is willing a contradiction: “Every rational being should tell the truth, except me.” This is special pleading: wanting the rule to apply to everyone but not to me. Such a contradiction is a failure of universalizability, the first formulation of the Categorical Imperative.

How does the reasoning work in practice?

Using practical reason, there are two steps to establish a bad act. First, we consider what we are proposing to do and for what reasons (i.e., on which maxim). Second, we consider whether we can will that everyone act on that maxim. If we cannot do so, we ought not to act on it ourselves. We must find some other maxim, one that passes the test.

Kant thinks there are two kinds of case where one could not will that everyone act on one’s maxim.

- Cases in which there simply could not be a world in which everyone acts on the maxim because everyone’s trying would be destructive of everyone’s continuing ability to do so, (he calls this a contradiction in nature):

“Some actions are so constituted that their maxim cannot even be conceived as a universal law of nature without contradiction.” (Kant, Groundwork 424)

- Cases where one can conceive of a world in which everyone acts on the maxim, but where one cannot consistently or rationally will such a world. (He calls this a contradiction in will)In either kind of case, the maxim will fail the CI test. According to Kant, it would be wrong to act on a maxim of either kind.

Kant’s examples of both kinds:

A contradiction in nature

The maxim: “When I believe myself to be in need to money I shall borrow money and promise to repay it, even though I know that this will never happen.”

A person proposes to make a promise he doesn’t intend to keep to pay back money in order to meet a need of his own. He must consider whether he could will a world in which everyone is motivated in precisely the same way. Kant claims that he cannot since it is only possible for people to promise in the first place if there is sufficient trust for others to believe that the person promising intends to keep his promise. But a world (otherwise like our own) in which everyone acted on this maxim would be a world in which such trust will not exist. Therefore it is impossible even to conceive of a world in which everyone acts on this maxim as though by a law of nature; therefore it is wrong to act on this maxim oneself.

- How far can this argument be taken? Would no maxim licensing a false promise, in circumstances of extreme need, say, be such that it could be willed to be a universal law?

b. How much of this example depends on the special “institutional” or “practical” features of promising. What if there were an evil practice that would similarly be destroyed by intentional departures from it? Would Kant’s theory argue against that?

A contradiction in will

The maxim: “let each be as happy as heaven wills or as he can make himself; I shall take nothing from him nor even envy him; only I do not care to contribute anything to his welfare or to his assistance in need!”

A person proposes not to help others because it is not in his own interest to do so. He then asks whether he could will a world in which everyone is similarly motivated.

Clearly he can imagine such a world, so this kind of case is different from the first. But can he rationally will that everyone act on this maxim as though by a law of nature? It seems he cannot, because in willing that he act on the maxim, he is willing that his own interest be promoted, but in willing that everyone act on the maxim, he is willing that his own interest not be promoted. Thus his will is in conflict with itself.

“Since many a situation might arise in which the man needed love and sympathy from others, and in which, by such a law of nature sprung from his own will, he would rob himself of all hope of the help he wants for himself.” (Groundwork,423)

For discussion: must we assume here that his interests are likelier to be promoted in a world in which people are motivated to help others in distress than in a world where they are not? Will this always be true? What if, given knowledge of his own relatively secure position, a person could rationally will the latter rather than the former world, but if he were ignorant of his privileged position would rationally prefer the former to the latter? What should we say then?

Note that Kant’s first example above also illustrates the idea of a contradiction in will. The person (in the example) who makes a lying promise uses the trust of others and the practice of promising for his own ends. But would these ends by promoted or harmed by everyone’s making such promises? If the latter, then he cannot rationally will that world and also will that his own ends be promoted by his making the lying promise. Therefore, it is wrong for him to make a lying promise to advantage himself.

Conclusion: a bad act is one that creates a contradiction in nature or will.

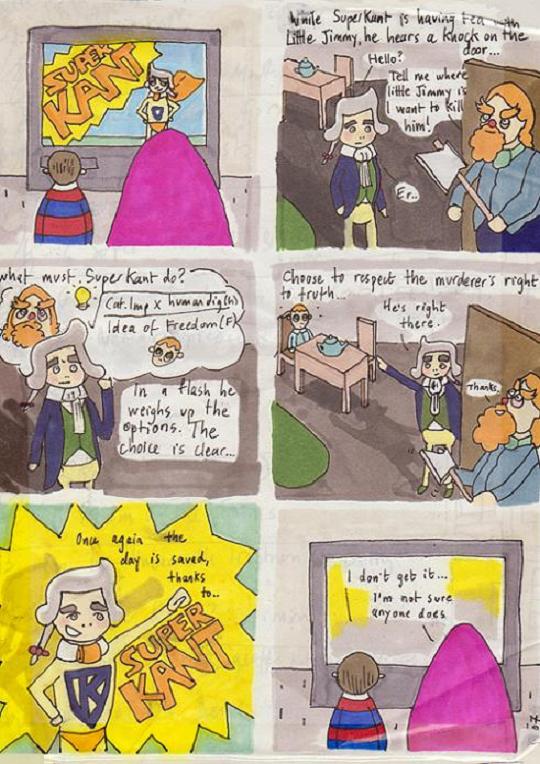

The strange case of the inquiring murderer

The strange case of the inquiring murderer is contained in an essay Kant wrote as a much older man, called “On a Supposed Right to lie from Altruistic Motives”. In it he asks us to consider the situation of a murderer just outside our friend’s house. The murderer asks us “is your friend inside?” How do we answer?

A cartoon of the Kantian dilemma by Rebecca Dyer: http://www.beingandtim.com/2010_05_01_archive.html

If I say “yes” there is a danger the murderer will go straight in and kill my friend. The speech bubble might read “Yes, one ought never to lie!”

If I say “no”, Kant argues that it is possible that my friend has slipped out, and the murderer will find him in the park and kill him, and if that’s the case, “you might justly be accused of causing his death”, and Kant concludes:

“Therefore, whoever tells a lie, however well intentioned he might be, must answer for the consequences, however unforeseeable they were, and pay the penalty for them….to be truthful (honest) in all deliberations, therefore, is a sacred and absolutely commanding decree of reason, limited to no expediency”. Immanuel Kant

How might Kant have reached this (to say the least) counter-intuitive answer?

Well, perhaps he saw that if all of us absolutely and always followed the categorical imperative, exercising the “good will” and universalizing our actions, then the summum bonum of a society which respected the moral “ought” and put it above feelings might just be realizable on this earth, and so we wouldn’t need the back door argument that we need God to put things straight and reward the virtuous in the next life.

If so, our poor friend has been sacrificed, as in the utilitarian position, for the greater good, and a teleological end. But do we really have to present the situation in such a stark way?

It seems to me that we can put some other things in speech bubbles which temper this truth-telling with wisdom. Rather than just say “yes” or “no”, it is no lie to ask a question for example.“Why do you want to know?” is not a lie, nor is a question necessarily implying we know the answer. “What makes you think I’ve got the faintest idea?

We might also deter the murderer by saying something like: “You lay a finger on my friend and I’ll kill you!” or even “Calm down, killing never solved anything!”

None of these answers breaks the categorical imperative (which doesn’t forbid us being evasive, aggressive or even vague!). Moreover, there is a basic logical flaw in this argument of Kant. If I am responsible for the unintended consequences of telling a lie, I must also be responsible for the unintended consequences of telling the truth.

Rachels (1994) goes further. He argues that consistency does not necessarily imply that we must accept rules without exceptions. In other words, the rules do not have to be absolute. We could have a rule “lying is wrong, unless we meet a situation where anyone who is rational would have to lie, such as saving a life”. In other words, if we can conceive of a rational person, acting out of duty, admitting the same exception to the rule, then we can universalise a rule-with-exceptions built in.

“All that is required by Kant’s basic idea is that when we violate a rule, we do so for a reason that we would be willing for anyone to accept, were they in our position” (1994:126)

Activity: In pairs spend a few minutes considering whether Rachels’ argument really works. Does it destroy the foundation of the “good will”, being that once we universalize a rule we must hold to it despite what feelings and circumstances incline us to do?

Want more? Click here for a full bibliography with summaries of all the issues in Kantian philosophy and ethics.

Strengths and weaknesses of Kantian ethics see TOPICS/Kant/strengths and weaknesses

Kant – four key quotes

“Two things fill me with wonder: the starry skies above and the moral law within”.

“So act that the maxim of your action can be willed as a universal law for all humanity”.

“Treat people not just as a means to an end, but also as an end in themselves”.

“Morality, by presupposing freedom, shows that our freedom is real; all other motives enslave us”.

Kant’s reason for developing the formula of ends (or humanity)

“I am an inquirer by inclination. I feel a consuming thirst for knowledge, the unrest which goes with the desire to progress in it, and satisfaction at every advance in it. There was a time when I believed this constituted the honour of humanity, and I despised the people, who know nothing. Rousseau set me right about this. This binding prejudice disappeared. I learned to honour humanity, and I would find myself more useless than the common labourer if I did not believe that this attitude of mine can give worth to all others in establishing the rights of humanity.”

What others say about Kant

- Alasdair MacIntyre

“The typical examples of Categorical Imperatives given by Kant tell us what not to do; not to break promises, tell lies, commit suicide, and so on. But as to what activities we ought to engage in, what ends we should pursue, the Categorical Imperative seems strangely silent”. (1967) - Mary Warnock

” The Categorical Imperative will really not do as an explanation of where ethics comes from. Its weakness lies in this separation of reason from emotion.” (1998) - J.B. Schneewind

” Given Kant’s Newtonian model of the physical world, a strong claim about the freedom of the will raises problems. Our bodies as physical objects are subject to Newton’s laws of motion. If they are moved by our natural desires, this is unproblematic, because desires themselves arise in accordance with deterministic laws (as yet undiscovered). Morality, however, requires the possibility of action from a non-empirical motive. We never know if real moral merit is attained, but if it is, the motive of respect for the moral law must move us to bodily action, regardless of the strength of our desires. Is this possible?” (ed Guyer 1992) - Peter Singer

“The difference between a value and a rule is that it makes sense to maximize a value – to increase it as much as possible – whereas we can only comply with a rule. So if I value happiness, I can choose between acts that will lead to there being more or less happiness in the world, but if I accept the rule that I should never kill an innocent human being, I can only comply with the rule, or break it….Consider this question: should I be ready to kill an innocent human being if, by doing so, I can somehow prevent the killing of several other innocent human beings? An affirmative answer suggests that you regard the reduction of killing of innocent human beings as a value; only a negative answer is consistent with treating the non-killing of innocent human beings as a rule”. (1994:11)

Activity: Fill in your own ideas in the blank spaces – with three strengths and three weaknesses

| Rigidity Kant gave the example of the murderer who asks: “is your friend hiding in the house?” and argued “to be honest in all deliberations is a sacred and absolutely commanding decree of reason…whoever tells a lie must answer for the consequences”. But aren’t we responsible too when we tell the truth and our friend is killed?

Kant believed that lying could not be adopted universally as a good thing because it would be self-defeating: trust would go and we would hurt each other. |

|

| Consistency We are consistent in how we apply rules (we don’t exempt ourselves or others), and how we treat people (as “ends” with dignity and rights).

“Moral reasons, if they are valid at all, are binding on all people at all times..it implies that a person cannot regard himself as special, from a moral point of view…that his interests are more important than others” Rachels (2007:126) |

Harshness – retribution Kant believed in an eye for an eye and hanging murderers: “an evil deed draws punishment on itself”. Respecting people’s rationality means holding them accountable for their actions. If someone is kind to you be kind back..and vice versa. Retribution (correct payment for wrongdoing) is good as it respects dignity and consistency.

“Reward and punishment are the natural expression of gratitude and resentment”. Rachels (2007:137) |

Exercise: Here are some quotes from philosophers responding to Kant. Try and put these criticisms in your own words and then consider the validity of these views.

- Alasdair MacIntyre

“The typical examples of alleged Categorical Imperatives given by Kant tell us what not to do; not to break promises, tell lies, commit suicide, and so on. But as to what activities we ought to engage in, what ends we should pursue, the Categorical Imperative seems strangely silent”. (1967) - Elisabeth Anscombe

“His own rigoristic convictions on the subject of lying were so intense that it never occurred to him that a lie could be relevantly described as anything but just a lie (eg “a lie in such-and-such circumstances”). His rule about universalizable maxims is useless withpout stipulations as to what shall count as a relevant description of an action with a view to constructing a maxim about it”. Philosophy 1958:2

- Mary Warnock

“The Categorical Imperative will really not do as an explanation of where ethics comes from. Its weakness lies in this separation of reason from all other human propensities.” (1998 - J.B. Schneewind

“ Given Kant’s Newtonian model of the physical world, a strong claim about the freedom of the will raises problems. Our bodies as physical objects are subject to Newton’s laws of motion. If they are moved by our natural desires, this is unproblematic, because desires themselves arise in accordance with deterministic laws (as yet undiscovered). Morality, however, requires the possibility of action from a non-empirical motive. We never know if real moral merit is attained, but if it is, the motive of respect for the moral law must move us to bodily action, regardless of the strength of our desires. Is this possible?” (ed Guyer 1992) - Peter Singer

“The difference between a value and a rule is that it makes sense to maximize a value – to increase it as much as possible – whereas we can only comply with a rule. So if I value happiness, I can choose between acts that will lead to there being more or less happiness in the world, but if I accept the rule that I should never kill an innocent human being, I can only comply with the rule, or break it….Consider this question: should I be ready to kill an innocent human being if, by doing so, I can somehow prevent the killing of several other innocent human beings? An affirmative answer suggests that you regard the reduction of killing of innocent human beings as a value; only a negative answer is consistent with treating the non-killing of innocent human beings as a rule”. (1994:11) - Anthony Quinton

The trouble with Kant, according to Anthony Quinton (Philosophy 72 [1997], 5–18), is that he does not take empirical experience to have any significant role to play in our knowledge of the world. The world we know is constituted through the imposition of a priori forms — space, time, substance and cause — on a ‘wholly passive sensory raw material’. This sensory material does not guide the manner in which the a priori forms are imposed in any way, so that the imposition is ‘entirely arbitrary’. Thus, Kant’s ‘account of the matter allows for an indefinitely large number of orders in which our successive manifolds of sensation could be arranged. None of these ways of distinguishing what there is and occurs from what I merely think is and occurs has any priority or superiority to any of the others’ (Quinton, 17–8).

Bibliography

O’Neill O. in Singer ed A companion to Ethics Blackwell (1993) Ch 14

Pojman, Louis Ethics, Discovering Right and Wrong (2006) Thomas Wadsworth Ch 7

Rachels J. The Elements of Moral Philosophy McGraw-Hill (1993) Ch 9&10

Raphael D.D. Moral Philosophy (second edition) Opus (1994) Ch 6

Schneewind J.B. in Guyer ed The Cambridge Companion to Kant CUP (1992) Ch 10

Scruton R. Kant (2001) OUP Ch 5

Quinton Anthony The Trouble with Kant Philosophy 72 (1997) 5-18

0 Comments