Regulating Campaign Finance

Campaign finance in the United States is the financing of electoral campaigns at the federal, state, and local levels.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Assess the origins, scope, and impact of money spent on election campaigns

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- At the federal level, campaign finance law is enacted by Congress and enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), an independent federal agency.

- Races for non-federal offices are governed by state and local law. Over half the states allow some level of corporate and union contributions.

- At the federal level, public funding is limited to subsidies for presidential campaigns. To receive subsidies in the primary, candidates must qualify by privately raising $5000 each in at least 20 states.

- In addition to primary matching funds, the public funding program also assists with financing the major parties’ presidential nominating conventions and funding the major party nominees’ general election campaigns.

- In 1971, Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), instituting various campaign finance disclosure requirements for federal candidates.

Key Terms

- public funding: At the federal level, public funding is limited to subsidies for presidential campaigns. This includes (1) a “matching” program for the first $250 of each individual contribution during the primary campaign, (2) financing the major parties’ national nominating conventions, and (3) funding the major party nominees’ general election campaigns.

- federal election commission: The Federal Election Commission (FEC) is an independent regulatory agency that was founded in 1975 by the United States Congress to regulate the campaign finance legislation in the United States.

Introduction

Campaign finance in the United States is the financing of electoral campaigns at the federal, state, and local levels. At the federal level, campaign finance law is enacted by Congress and enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), an independent federal agency. Although most campaign spending is privately financed, public financing is available for qualifying candidates for President of the United States during both the primaries and the general election. Eligibility requirements must be fulfilled to qualify for a government subsidy, and those that do accept government funding are usually subject to spending limits.

Federal Elections Commission: Seal of the United States Federal Election Commission.

Races for non-federal offices are governed by state and local law. Over half the states allow some level of corporate and union contributions. Some states have limits on contributions from individuals that are lower than the national limits, while four states (Missouri, Oregon, Utah and Virginia) have no limits at all.

Campaign Finance Numbers

In 2008—the last presidential election year—candidates for office, political parties, and independent groups spent a total of $5.3 billion on federal elections. The amount spent on the presidential race alone was $2.4 billion, and over $1 billion of that was spent by the campaigns of the two major candidates: Barack Obama spent $730 million in his election campaign, and John McCain spent $333 million. In the 2010 midterm election cycle, candidates for office, political parties, and independent groups spent a total of $3.6 billion on federal elections. The average winner of a seat in the House of Representatives spent $1.4 million on his or her campaign. The average winner of a Senate seat spent $9.8 million.

Public financing of campaigns

At the federal level, public funding is limited to subsidies for presidential campaigns. This includes (1) a “matching” program for the first $250 of each individual contribution during the primary campaign, (2) financing the major parties’ national nominating conventions, and (3) funding the major party nominees’ general election campaigns.

To receive subsidies in the primary, candidates must qualify by privately raising $5000 each in at least 20 states. During the primaries, in exchange for agreeing to limit his or her spending according to a statutory formula, eligible candidates receive matching payments for the first $250 of each individual contribution (up to half of the spending limit). By refusing matching funds, candidates are free to spend as much money as they can raise privately.

From the inception of this program in 1976 through 1992, almost all candidates who could qualify accepted matching funds in the primary. In 1996 Republican Steve Forbes opted out of the program. In 2000, Forbes and George W. Bush opted out. In 2004 Bush and Democrats John Kerry and Howard Dean chose not to take matching funds in the primary. In 2008, Democrats Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, and Republicans John McCain, Rudy Giuliani, Mitt Romney and Ron Paul decided not to take primary matching funds. Republican Tom Tancredo and Democrats Chris Dodd, Joe Biden and John Edwards elected to take public financing.

In addition to primary matching funds, the public funding program also assists with financing the major parties’ (and eligible minor parties’) presidential nominating conventions and funding the major party (and eligible minor party) nominees’ general election campaigns. The grants for the major parties’ conventions and general election nominees are adjusted each Presidential election year to account for increases in the cost of living. In 2012, each major party is entitled to $18.2 million in public funds for their conventions, and the parties’ general election nominees are eligible to receive $91.2 million in public funds. If candidates accept public funds, they agree not to raise or spend private funds or to spend more than $50,000 of their personal resources.

Sources of Campaign Funding

Different sources of campaign funding help party candidates to raise funds through multiple avenues.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Identify the varied sources and roles of money in campaigns and politics

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- Corporations and unions are barred from donating money directly to candidates or national party committees.

- Lobbying in the United States describes paid activity in which special interests hire well-connected professional advocates, often lawyers, to argue for specific legislation in decision-making bodies such as the United States Congress.

- Federal law allows for multiple types of Political Action Committees, including connected PACs, nonconnected PACs, leadership PACs, Super PACs.

- A 527 organization is a type of American tax-exempt organization named after “Section 527” of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code.

- Political party committees may contribute funds directly to candidates, subject to the specified contribution limits.

- Different sources of campaign funding help party candidates to raise funds through multiple avenues. Campaign finance in the United States is the financing of electoral campaigns at the federal, state, and local levels.

Key Terms

- 527 organization: A 527 organization is a type of American tax-exempt organization named after “Section 527” of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. Technically, almost all political committees, including state, local, and federal candidate committees, traditional political action committees, “Super PACs”, and political parties are “527s. “

- lobbying: Lobbying (also lobby) is the act of attempting to influence decisions made by officials in the government, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies.

- bundlers: Bundlers are people who can gather contributions from many individuals in an organization or community and present the sum to the campaign. Campaigns often recognize these bundlers with honorary titles and, in some cases, exclusive events featuring the candidate.

Sources of Campaign Funding

Different sources of campaign funding enable party candidates raise funds through multiple avenues. Campaign finance in the United States is the financing of electoral campaigns at the federal, state, and local levels. At the federal level, campaign finance law is enacted by Congress and enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), an independent federal agency. Although most campaign spending is privately financed, public financing is also available for qualifying candidates for President of the United States during both the primaries and the general election. Eligibility requirements must be met to qualify for a government subsidy, and those that accept government funding are usually subject to spending limits. Federal law restricts how much individuals and organizations may contribute to political campaigns, political parties, and other FEC-regulated organizations.

Corporations and unions are barred from donating money directly to candidates or national party committees. One consequence of the limitation upon personal contributions from any one individual is that campaigns seek out ” bundlers “—people who can gather contributions from many individuals in an organization or community and present the sum to the campaign. Campaigns often recognize these bundlers with honorary titles and, in some cases, exclusive events featuring the candidate. Although bundling had existed in various forms since the enactment of the FECA, it became more structured and organized in the 2000s, spearheaded by the “Bush Pioneers” for George W. Bush’s 2000 and 2004 presidential campaigns. During the 2008 campaign, the six leading primary candidates (three Democratic, three Republican) had listed a total of nearly two thousand bundlers.

Lobbying and Special Interests

Lobbying in the United States describes paid activity in which special interests hire well-connected professional advocates, often lawyers, to argue for specific legislation in decision-making bodies such as the United States Congress. It is a highly controversial phenomenon, often seen in a negative light by journalists and the American public, and frequently misunderstood. While lobbying is subject to extensive and often complex rules which, if not followed, can lead to penalties including jail, the activity of lobbying has been interpreted by court rulings as free speech and protected by the Constitution.

Tony Podesta, Senator Kay and Chip Hagan: Lobbying depends on cultivating personal relationships over many years. Photo: Lobbyist Tony Podesta (left) with Senator Kay Hagan (center) and her husband.

Spending by Outside Organizations

Federal law allows for multiple types of Political Action Committees, including connected PACs, nonconnected PACs, leadership PACs and Super PACs. 501(c)(4) organizations are defined by the IRS as “social welfare ” organizations. Unlike 501(c)(3) charitable organizations, they may also participate in political campaigns and elections, as long as the organization’s “primary purpose” is the promotion of social welfare and not political advocacy. A 527 organization is a type of American tax-exempt organization named after “Section 527” of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. Technically, almost all political committees, including state, local, and federal candidate committees, traditional political action committees, “Super PACs”, and political parties are “527s. ” However, in common practice the term is usually applied only to such organizations that are not regulated under state or federal campaign finance laws because they do not “expressly advocate” for the election or defeat of a candidate or party.

Political party committees may contribute funds directly to candidates, subject to the specified contribution limits. National and state party committees may make additional “coordinated expenditures,” subject to limits, to help their nominees in general elections. National party committees may also make unlimited “independent expenditures” to support or oppose federal candidates. However, since 2002, national parties have been prohibited from accepting any funds outside the limits established for elections in the FECA.

PACs and Campaigns

A political action committee is any organization that campaigns for or against political candidates, ballot initiatives or legislation.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Analyze the role of PACs in federal elections

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- At the federal level, an organization becomes a PAC when it receives or spends more than $1,000 for the purpose of influencing a federal election, according to the Federal Election Campaign Act.

- Individuals are limited to contributing $5,000 per year to Federal PACs; corporations and unions may not contribute directly to federal PACs, but can pay for the administrative costs.

- Federal law allows for two types of PACs, connected and non-connected. Most of the 4,600 active, registered PACs are “connected PACs” established by businesses, labor unions, trade groups, or health organizations. By contrast, “non-connected PACs” have an ideological mission.

- Super PACs may not make contributions to candidate campaigns or parties, but may engage in unlimited political spending independently of the campaigns. Unlike traditional PACs, they can raise funds from corporations, unions and other groups, and from individuals, without legal limits.

- In 2010, the United States Supreme Court held in “Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission” that it is legal for corporations and unions to spend from their general treasuries to finance independent expenditures.

Key Terms

- super pacs: Super PACs, officially known as “independent-expenditure only committees,” may not make contributions to candidate campaigns or parties, but may engage in unlimited political spending independently of the campaigns. Also unlike traditional PACs, they can raise funds from corporations, unions and other groups, and individuals—without legal limits.

- citizens united: In 2010, the United States Supreme Court held in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that laws prohibiting corporate and union political expenditures were unconstitutional. Citizens United made it legal for corporations and unions to finance independent expenditures with money from their general treasuries. It did not alter the prohibition on direct corporate or union contributions to federal campaigns—those are still prohibited.

- political action committee: A political action committee (PAC) is any organization in the United States that campaigns for or against political candidates, ballot initiatives, or legislation.

Introduction

A political action committee (PAC) is any organization in the United States that campaigns for or against political candidates, ballot initiatives or legislation. At the federal level, an organization becomes a PAC when it receives or spends more than $1,000 for the purpose of influencing a federal election, according to the Federal Election Campaign Act. At the state level, an organization becomes a PAC according to the state’s election laws.

In 2010, the United States Supreme Court held in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that laws prohibiting corporate and union political expenditures were unconstitutional. Citizens United made it legal for corporations and unions to spend from their general treasuries to finance independent expenditures, but did not alter the prohibition on direct corporate or union contributions to federal campaigns; those are still prohibited.

History of PACs in the United States

In 1947, as part of the Taft-Hartley Act, the U.S. Congress prohibited labor unions or corporations from spending money to influence federal elections, and prohibited labor unions from contributing to candidate campaigns. Labor unions moved to work around these limitations by establishing political action committees, to which members could contribute. In 1971, Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA). In 1974, Amendments to FECA defined how a PAC could operate and established the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to enforce the nation’s campaign finance laws. The FECA and the FEC’s rules provide for the following: Individuals are limited to contributing $5,000 per year to Federal PACs; corporations and unions may not contribute directly to federal PACs, but can pay for the administrative costs of a PAC affiliated with the specific corporation or union; Corporate-affiliated PACs may only solicit contributions from executives, shareholders, and their families.

Categorization of PACs

Federal law allows for two types of PACs, connected and non-connected. Most of the 4,600 active, registered PACs are “connected PACs” established by businesses, labor unions, trade groups, or health organizations. These PACs receive and raise money from a “restricted class,” generally consisting of managers and shareholders in the case of a corporation and members in the case of a union or other interest group. Groups with an ideological mission, single-issue groups, and members of Congress and other political leaders may form “non-connected PACs. ” These organizations may accept funds from any individual, connected PAC, or organization.

Super PACs, officially known as “independent-expenditure only committees,” may not make contributions to candidate campaigns or parties, but may engage in unlimited political spending independently of the campaigns. Also unlike traditional PACs, they can raise funds from corporations, unions and other groups, and from individuals, without legal limits. Super PACs may support particular candidacies. In the 2012 presidential election, super PACs have played a major role, spending more than the candidates’ election campaigns in the Republican primaries. As of early April 2012, Restore Our Future—a Super PAC usually described as having been created to help Mitt Romney ‘s presidential campaign—has spent $40 million. In the 2012 election campaign, most of the money given to super PACs has come not from corporations but from wealthy individuals. According to data from the Center for Responsive Politics, the top 100 individual super PAC donors in 2011–2012 made up just 3.7% of contributors, but accounted for more than 80% of the total money raised, while less than 0.5% of the money given to “the most active Super PACs” was donated by publicly traded corporations.

Mitt Romney: Governor Mitt Romney of Massachusetts was the Republican candidate for the 2012 presidential election.

PAC Backlash

It was generally agreed in the 2012 campaign that the formation of a super PAC and the acceptance of large contributions was legal. However, a lingering question was whether super PACs are legal when examined on the basis of how they act. Two agreed-upon illegal actions were that a super PAC could not accept foreign funds and could not coordinate directly with a candidate. Super PACs were seen in the press as a possible means of allowing illegal donations from foreign entities – either individuals or companies – to be disguised. The concept of actions being illegal, when coordinated with a candidate, came out, in part, after a super PAC named American Crossroads requested permission to communicate to their favored candidate on an above-board basis.

International Comparison and Response

The leading democracies have different systems of campaign finance, and several have no institutions analogous to American PACs, in that there are no private contributions of large sums of money to individual candidates. This is true, for example in Germany, in France, and in Britain. In these countries, concerns about the influence of campaign contributions on political decisions are less prominent in public discussion.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission

The Citizens United case held that it was unconstitutional to ban campaign financial contributions by corporations, associations and unions.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Analyze the significance of the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission for campaign finance reform

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission was a landmark United States Supreme Court case in 2010 in which the court held that the First Amendment prohibited the government from restricting independent political expenditures by corporations and unions.

- The nonprofit group Citizens United wanted to air a film critical of Hillary Clinton and to advertise the film during television broadcasts in apparent violation of the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. In a 5 to 4 decision, the court held that portions of BCRA violated the First Amendment.

- The Supreme Court held that it was unconstitutional to ban free speech through the limitation of independent communications by corporations, associations, and unions. This ruling was frequently interpreted as permitting corporate corporations and unions to donate to political campaigns.

- Citizens United has often been credited for the creation of “super PACs,” political action committees which make no contributions to candidates or parties and so can accept unlimited contributions from individuals, corporations, and unions.

Key Terms

- Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission: Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission was a landmark United States Supreme Court case in 2010 in which the court held that the First Amendment prohibited the government from restricting independent political expenditures by corporations and unions.

- super pacs: Political action committees, which make no contributions to candidates or parties, and so can accept unlimited contributions from individuals, corporations, and unions.

Introduction

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission was a landmark United States Supreme Court case in 2010 in which the court held that the First Amendment prohibited the government from restricting independent political expenditures by corporations and unions. The nonprofit group Citizens United wanted to air a film critical of Hillary Clinton and to advertise the film during television broadcasts in apparent violation of the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. In a 5 to 4 decision, the court held that portions of BCRA violated the First Amendment.

Background

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 prohibited corporations and unions from using their general treasury to fund “electioneering communications” within 30 days before a primary or 60 days before a general election. During the 2004 presidential campaign, a conservative nonprofit organization named Citizens United filed a complaint before the Federal Election Commission (FEC) charging that advertisements for Michael Moore’s film, Fahrenheit 9/11, a documentary critical of the Bush administration’s response to the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, constituted political advertising and thus could not be aired within the 30 days before a primary election or 60 days before a general election. The FEC dismissed the complaint after finding no evidence that broadcast advertisements for the movie and featuring a candidate within the proscribed time limits had actually been made.

In the wake of these decisions, Citizens United sought to establish itself as a bona fide commercial filmmaker, producing several documentary films between 2005 and 2007. By early 2008, it sought to run television commercials to promote its latest political documentary, Hillary: The Movie, and to air the movie on DirecTV. The movie was highly critical of then-Senator Hillary Clinton, with the District Court describing the movie as an elongated version of a negative 30-second television spot. In January 2008, the United States District Court for the District of Columbia ruled that the television advertisements for Hillary: The Movie violated the BCRA restrictions of “electioneering communications” within 30 days of a primary. Though the political action committee claimed that the film was fact-based and nonpartisan, the lower court found that the film had no purpose other than to discredit Clinton’s candidacy for president. The Supreme Court docketed the case on August 18, 2008 and heard oral argument on March 24, 2009.

Opinions of the Court

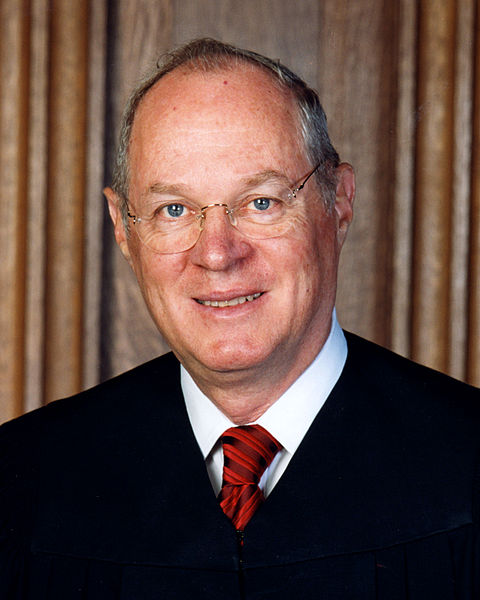

The Supreme Court held in Citizens United that it was unconstitutional to ban free speech through the limitation of independent communications by corporations, associations and unions. This ruling was frequently interpreted as permitting corporate corporations and unions to donate to political campaigns, or else removing limits on how much a donor can contribute to a campaign. Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion found that the BCRA prohibition of all independent expenditures by corporations and unions violated the First Amendment’s protection of free speech.

Justice Anthony Kennedy: Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion found that the BCRA prohibition of all independent expenditures by corporations and unions violated the First Amendment’s protection of free speech.

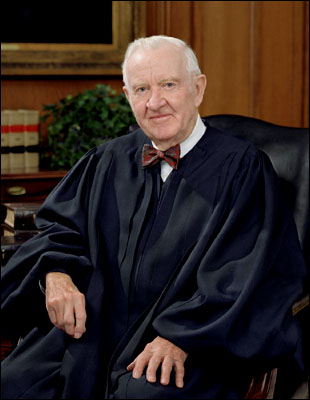

A dissenting opinion by Justice Stevens was joined by Justice Ginsburg, Justice Breyer, and Justice Sotomayor. Stevens concurred in the court’s decision to sustain BCRA’s disclosure provisions, but dissented from the principal holding of the majority opinion. The dissent argued that the court’s ruling “threatens to undermine the integrity of elected institutions across the Nation. The path it has taken to reach its outcome will, I fear, do damage to this institution. ” He wrote: “A democracy cannot function effectively when its constituent members believe laws are being bought and sold. ”

Justice John Paul Stevens: John Paul Stevens wrote a dissenting opinion, arguing that the Court’s ruling “threatens to undermine the integrity of elected institutions across the Nation. “

Impact

On January 27, 2010, President Barack Obama condemned the decision during the 2010 State of the Union Address, stating that, “Last week, the Supreme Court reversed a century of law to open the floodgates for special interests — including foreign corporations — to spend without limit in our elections. ” Moreover, The New York Times stated in an editorial, “The Supreme Court has handed lobbyists a new weapon. A lobbyist can now tell any elected official: if you vote wrong, my company, labor union or interest group will spend unlimited sums explicitly advertising against your re-election. ” The New York Times reported that 24 states with laws prohibiting or limiting independent expenditures by unions and corporations would have to change their campaign finance laws because of the ruling.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission has often been credited for the creation of “super PACs”, political action committees which make no contributions to candidates or parties and so can accept unlimited contributions from individuals, corporations, and unions. In the 2012 presidential election, super PACs have played a major role, spending more than the candidates’ election campaigns in the Republican primaries. As of early April 2012, Restore Our Future—a Super PAC usually described as having been created to help Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign—has spent $40 million.

Campaign Finance Reform

In the U.S., campaign finance reform is the common term for the political effort to change the involvement of money in political campaigns.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Identify major legislative and judicial milestones in campaign finance reform in the United States

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- The Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) of 1972 required candidates to disclose sources of campaign contributions and campaign expenditures. It was amended in 1974 with the introduction of statutory limits on contributions, and creation of the Federal Election Commission (FEC).

- The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002, is the most recent major federal law on campaign finance, which revised some of the legal limits on expenditures set in 1974, and prohibited unregulated contributions to national political parties.

- The voting with dollars plan would establish a system of modified public financing coupled with an anonymous campaign contribution process. It has two parts: patriot dollars and the secret donation booth.

- Another method allows the candidates to raise funds from private donors, but provides matching funds for the first chunk of donations. This would effectively make small donations more valuable to a campaign, potentially leading them to put more effort into pursuing such donations.

- Another method, which supporters call clean money, clean elections, gives each candidate who chooses to participate a certain, set amount of money. In order to qualify for this money, the candidates must collect a specified number of signatures and small (usually $5) contributions.

Key Terms

- federal election campaign act: The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 is a United States federal law which increased disclosure of contributions for federal campaigns. It was amended in 1974 to place legal limits on the campaign contributions.

Introduction

Campaign finance reform is the common term for the political effort in the United States to change the involvement of money in politics, primarily in political campaigns. Although attempts to regulate campaign finance by legislation date back to 1867, the first successful attempts nationally to regulate and enforce campaign finance originated in the 1970s. The Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) of 1972 required candidates to disclose sources of campaign contributions and campaign expenditures. It was amended in 1974 with the introduction of statutory limits on contributions, and creation of the Federal Election Commission (FEC). It attempted to restrict the influence of wealthy individuals by limiting individual donations to $1,000 and donations by political action committees (PACs) to $5,000. These specific election donations are known as ‘hard money. ‘ The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002, is the most recent major federal law on campaign finance, which revised some of the legal limits on expenditures set in 1974, and prohibited unregulated contributions to national political parties.

Federal Election Campaign Act

In 1971, Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act, requiring broad disclosure of campaign finance. In 1974, fueled by public reaction to the Watergate Scandal, Congress passed amendments to the Act establishing a comprehensive system of regulation and enforcement, including public financing of presidential campaigns and creation of a central enforcement agency, the Federal Election Commission. Other provisions included limits on contributions to campaigns and expenditures by campaigns, individuals, corporations and other political groups. However, in 1976 Buckley v. Valeo challenged restrictions in FECA as unconstitutional violations of free speech. The court struck down, as infringement on free speech, limits on candidate expenditures and certain other limits on spending.

Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002

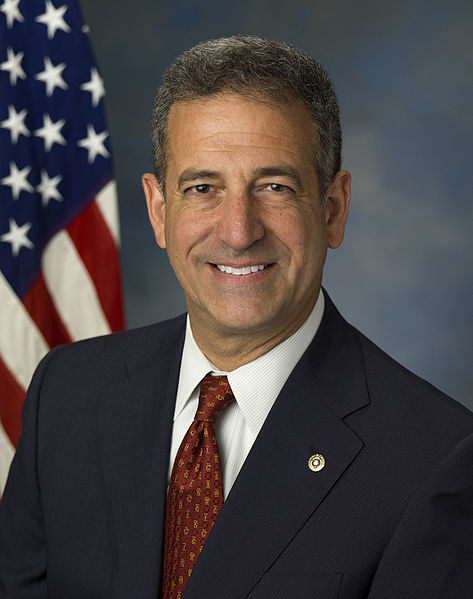

Russ Feingold: Senator Russ Feingold from Wisconsin.

The Congress passed the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), also called the McCain-Feingold bill after its chief sponsors, John McCain and Russ Feingold. The BCRA was a mixed bag for those who wanted to remove big money from politics. It eliminated all soft money donations to the national party committees, but it also doubled the contribution limit of hard money, from $1,000 to $2,000 per election cycle, with a built-in increase for inflation. In addition, the bill aimed to curtail ads by non-party organizations by banning the use of corporate or union money to pay for “electioneering communications,” a term defined as broadcast advertising that identifies a federal candidate within 30 days of a primary or nominating convention, or 60 days of a general election.

Current proposals for reform

The voting with dollars plan would establish a system of modified public financing coupled with an anonymous campaign contribution process. It has two parts: patriot dollars and the secret donation booth. It was originally described in detail by Yale Law School professors Bruce Ackerman and Ian Ayres in their 2004 book Voting with Dollars: A new paradigm for campaign finance. All voters would be given a $50 publicly funded voucher (Patriot dollars) to donate to federal political campaigns. All donations including both the $50 voucher and additional private contributions must be made anonymously through the FEC. Ackerman and Ayres include model legislation in their book in addition to detailed discussion as to how such a system could be achieved and its legal basis.

Another method allows the candidates to raise funds from private donors, but provides matching funds for the first chunk of donations. For instance, the government might “match” the first $250 of every donation. This would effectively make small donations more valuable to a campaign, potentially leading them to put more effort into pursuing such donations, which are believed to have less of a corrupting effect than larger gifts and enhance the power of less-wealthy individuals. Such a system is currently in place in the U.S. presidential primaries.

Another method, which supporters call clean money, clean elections, gives each candidate who chooses to participate a certain, set amount of money. In order to qualify for this money, the candidates must collect a specified number of signatures and small (usually $5) contributions. The candidates are not allowed to accept outside donations or to use their own personal money if they receive this public funding. Candidates receive matching funds, up to a limit, when they are outspent by privately-funded candidates, attacked by independent expenditures, or their opponent benefits from independent expenditures. This is the primary difference between clean money public financing systems and the presidential campaign system, which many have called “broken” because it provides no extra funds when candidates are attacked by 527s or other independent expenditure groups.

The Federal Election Campaign Act

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 is a United States federal law which increased disclosure of contributions for federal campaigns.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Describe the history of campaign finance regulation in the twentieth century

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- The Federal Election Commission (FEC) is an independent regulatory agency that was founded in 1975 by the United States Congress to regulate the campaign finance legislation.

- Early legislation by Congress sought to limit the influence of wealthy individuals and special interest groups on the outcome of federal elections, regulate spending in campaigns for federal office, and deter abuses by mandating public disclosure of campaign finances.

- A political action committee ( PAC ) is any organization in the United States that campaigns for or against political candidates, ballot initiatives, or legislation.

- In Buckley v. Valeo (1976), the Supreme Court upheld a federal law which set limits on campaign contributions, but it also ruled that spending money to influence elections is a form of constitutionally protected free speech, striking down portions of FECA.

- With the Buckley v. Valeo decision, the Supreme Court also ruled that candidates can give unlimited amounts of money to their own campaigns.

- Following Buckley v. Valeo, the Federal Elections Campaign Act was amended in 1976 and 1979 with the goal to allow parties to spend unlimited amounts of soft money on activities like increasing voter turnout and registration. This led to passage of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act in 2002.

Key Terms

- federal election campaign act: The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 is a United States federal law which increased disclosure of contributions for federal campaigns. It was amended in 1974 to place legal limits on the campaign contributions.

- federal election commission: The Federal Election Commission (FEC) is an independent regulatory agency that was founded in 1975 by the United States Congress to regulate the campaign finance legislation in the United States.

- political action committee: A political action committee (PAC) is any organization in the United States that campaigns for or against political candidates, ballot initiatives, or legislation.

Introduction

Federal Elections Commission: Seal of the United States Federal Election Commission.

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 is a United States federal law which increased disclosure of contributions for federal campaigns. It was amended in 1974 to place legal limits on the campaign contributions. The amendment also created the Federal Election Commission (FEC), an independent agency responsible for regulating campaign finance legislation. The FEC describes its duties as “to disclose campaign finance information, to enforce the provisions of the law such as the limits and prohibitions on contributions, and to oversee the public funding of Presidential elections.”

History

As early as 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt asserted the need for campaign finance reform and called for legislation to ban corporate contributions for political purposes. In response, the United States Congress enacted the Tillman Act of 1907, named for its sponsor Senator Benjamin Tillman. This act banned corporate contributions. Further regulation followed with the Federal Corrupt Practices Act enacted in 1910 with subsequent amendments in 1910 and 1925, the Hatch Act, the Smith-Connally Act of 1943, and the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947. These acts sought to:

- Limit the influence of wealthy individuals and special interest groups on the outcome of federal elections.

- Regulate spending in campaigns for federal office.

- Deter abuses by mandating public disclosure of campaign finances.

In 1971, Congress consolidated earlier reform efforts in the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), instituting more stringent disclosure requirements for federal candidates, political parties and political action committees. A political action committee(PAC) is any organization in the United States that campaigns for or against political candidates, ballot initiatives, or legislation. According to the FECA, an organization becomes a PAC when it receives or spends more than $1,000 for the purpose of influencing a federal election. Without a central administrative authority, campaign finance laws were difficult to enforce.

Public subsidies for federal elections, originally proposed by President Roosevelt in 1907, began to take shape as part of FECA. Congress established the income tax checkoff to provide financing for Presidential general election campaigns and national party conventions. Amendments to the Internal Revenue Code in 1974 established the matching fund program for Presidential primary campaigns. Following reports of serious financial abuses in the 1972 Presidential campaign, Congress amended the FECA in 1974 to set limits on contributions by individuals, political parties, and PACs. The 1974 amendments also established the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to enforce the law, facilitate disclosure, and administer the public funding program. The FEC opened its doors in 1975 and administered the first publicly funded Presidential election in 1976.

Buckley v. Valeo

In Buckley v. Valeo (1976), the Supreme Court struck down or narrowed several provisions of the 1974 amendments to FECA, including limits on spending and limits on the amount of money a candidate could donate to his or her own campaign. The court upheld a federal law which set limits on campaign contributions, but it also ruled that spending money to influence elections is a form of constitutionally protected free speech, striking down portions of the law. The court also ruled candidates can give unlimited amounts of money to their own campaigns.

Further Legislation

Following Buckley v. Valeo, FECA was amended again in 1976 and 1979. The aim of these amendments was to allow parties to spend unlimited amounts of hard money on activities like increasing voter turnout and registration. In 1979, the Commission ruled that political parties could spend unregulated or “soft” money for non-federal administrative and party building activities. Later, this money was used for candidate related issue ads, leading to a substantial increase in soft money contributions and expenditures in elections. The increase of soft money created political pressures that led to passage of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA). The BCRA banned soft money expenditure by parties. Some of the legal limits on giving of “hard money” were also changed in by BCRA.

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 is a United States federal law that regulates the financing of political campaigns.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Analyze the history of legal challenges to campaign finance reform legislation

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- The Act was designed to address two issues: the increased role of soft money in campaign financing, and the proliferation of issue advocacy ads.

- Soft money refers to “non-federal money” that corporations, unions and individuals contribute to political parties to influence state or local elections.

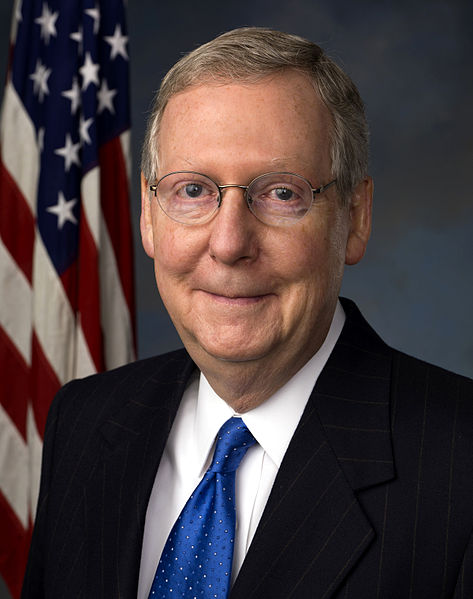

- Provisions of the legislation were challenged as unconstitutional by a group of plaintiffs led by then– Senate Majority Whip Mitch McConnell, a long-time opponent of the bill.

- “McConnell v. Federal Election Commission” is a case in which the United States Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of most of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA).

- The impact of BCRA was felt nationally during the 2004 elections. One impact was that all campaign advertisements included a verbal statement to the effect of “I’m ( candidate ‘s name) and I approve this message.

Key Terms

- bipartisan campaign reform act: The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 is a United States federal law amending the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 regulating the financing of political campaigns.

- soft money: Soft money refers to “non-federal money” that corporations, unions and individuals contribute to political parties to influence state or local elections.

- mcconnell v. federal election commission: In McConnell v. Federal Election Commission, the United States Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of most of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA).

Introduction

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 is a United States federal law amending the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 regulating the financing of political campaigns. Its chief sponsors were Senators Russ Feingold (, D-WI) and John McCain (, R-AZ). The law became effective on November 6, 2002, with the new legal limits going into effect on January 1, 2003. Although the legislation is known as “McCain–Feingold,” the Senate version is not the bill that became law. Instead, the companion legislation introduced by Rep. Chris Shays (R-CT),H.R. 2356, is the version that became law. Shays–Meehan was originally introduced as H.R. 380.

2008 Republican Party Presidential Candidate John McCain: Senator John McCain from Arizona.

Russ Feingold: Senator Russ Feingold from Wisconsin.

The Act addresses the increased role of soft money in campaign financing by prohibiting national political party committees from raising or spending funds not subject to federal limits. Soft money refers to “non-federal money” that corporations, unions and individuals contribute to political parties to influence state or local elections. The Act also addresses proliferation of issue advocacy ads, defining as “electioneering communications” broadcast ads that name a federal candidate within 30 days of a primary or caucus or 60 days of a general election. Any such ad paid for by a corporation or a non-profit organizations is also prohibited.

In June 2003, the D.C. Circuit issued a ruling on the constitutionality of the law, but the ruling never took effect as the case was immediately appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Mitch McConnell: Official portrait of United States Senator Mitch McConnell (R-KY)

Legal Disputes

Provisions of the legislation were challenged as unconstitutional by a group of plaintiffs led by then–Senate Majority WhipMitch McConnell. President Bush signed the law despite “reservations about the constitutionality of the broad ban on issue advertising. ” Bush appeared to expect that the Supreme Court would overturn some of its key provisions. However, in December 2003, the Supreme Court upheld most of the legislation in McConnell v. Federal Election Commission.

In McConnell v. Federal Election Commission, the United States Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of most of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA). The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a special session on September 8, 2003. On December 10, 2003, it issued a complicated decision that upheld the key provisions of McCain-Feingold. These included “electioneering communication” provisions placing restrictions on using corporate and union treasury funds to disseminate broadcast ads identifying a federal candidate within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election) The court also upheld the “soft money” ban prohibiting the raising or use of these funds in federal elections.

Impact and Overturn

The impact of BCRA was felt nationally during the 2004 elections. One immediately recognizable impact was the so-called “Stand By Your Ad” provision. The provision requires all U.S. political candidates and parties to identify themselves and state that they have approved a particular communication, i.e. “I’m (a candidate) and I approve this message. ”

In Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc., the Supreme Court ruled that the organizations engaged in genuine discussion of issues were entitled to a broad, “as applied” exemption from the electioneering communications provisions of BCRA applying to naming a candidate before an election or primary. Observers argue that the Court’s exemption effectively nullifies those provisions of the Act, but the full impact of Wisconsin Right to Life remains to be seen.

Campaign Financing

Campaign finance in the United States refers to the process of financing electoral campaigns at the federal, state, and local levels.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Describe the nature of and uses for campaign finance in the United States

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- At the federal level, campaign finance law is enacted by Congress and enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), an independent federal agency.

- Political finance refers to all funds that are raised and spent for political purposes. This includes all political contests for voting by citizens, especially the election campaigns for various public offices.

- Political expenses can be caused by election campaigns or contests for nomination or re-selection of parliamentary candidates.

Key Terms

- political finance: Political finance covers all funds that are raised and spent for political purposes. Such purposes include all political contests for voting by citizens, especially the election campaigns for various public offices that are run by parties and candidates.

- grassroots fundraising: Grassroots fundraising is a method of fundraising used by or for political candidates, which has grown in popularity with the emergence of the Internet and its use by US presidential candidates like Howard Dean and Ron Paul.

Introduction

Campaign finance in the United States refers to the process of financing electoral campaigns at the federal, state, and local levels. At the federal level, campaign finance law is enacted by Congress and enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), an independent federal agency. Although most campaign spending is privately financed, public financing is available for qualifying US presidential candidates during both the primaries and the general election. Eligibility requirements must be fulfilled to qualify for a government funding, and candidates who accept this funding are usually subject to spending limits.

Political Finance

Political finance refers to all funds that are raised and spent for political purposes. This includes all political contests for voting by citizens, especially the election campaigns for various public offices. Modern democracies operate a variety of permanent party organizations. For example, in the United States this includes the Democratic National Committee and the Republican National Committee. Political expenses can include:

- Election campaigns run by candidates, candidate committees, interest groups or political parties

- Contests for nomination or re-selection of parliamentary candidates

- Training activities for party activists, officeholders or candidates

- Efforts to educate citizens with regard to popular initiatives, ballot issues or referendums.

Grassroots fundraising is a method of fundraising used by or for political candidates. This method has grown in popularity with the emergence of the Internet and its use by US presidential candidates like Howard Dean and Ron Paul. Grassroots fundraising is a way of financing campaigns for candidates who don’t have significant media exposure or candidates who are in opposition to the powerful lobby groups. It often involves mobilizing grassroots support to meet a specific fundraising goal, or it sets a specific day for grassroots supporters to donate to the campaign.

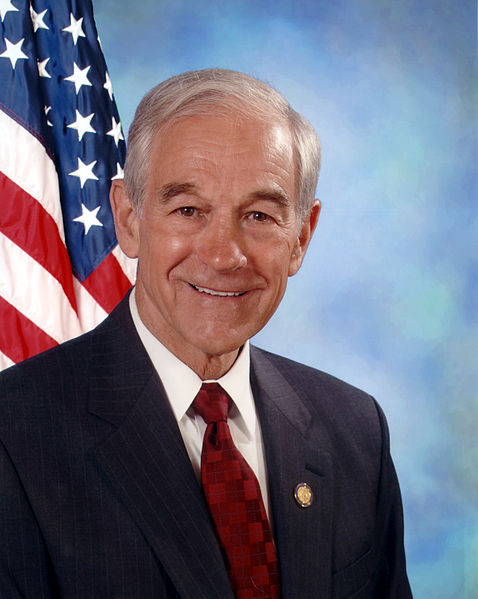

Ron Paul: Ron Paul is a congressman from Texas who employs the method of grassroots fundraising.

0 Comments