Article: Trust, politics and institutions

4th September 2015

Trust, politics and institutions

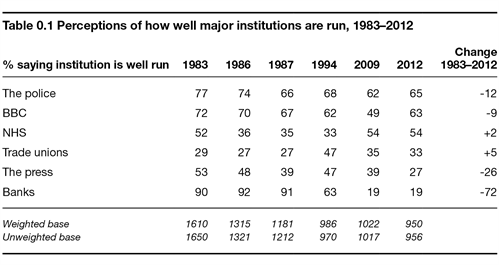

Source: Social Attitudes Survey (30)

What might we expect to happen to people’s sense of trust and obligation in a supposedly more individualised society? If people are choosing their own lifestyles (rather than being socialised into traditional patterns of thought and behaviour), traditional common bonds of obligation – for instance, the notion that citizens have a “duty to vote” – might no longer have the force they once did. We have already seen that fewer people now identify with a particular political party; if people’s sense of involvement and participation in the political process is promoted by attachment to a political party, we would also expect this decline to have an impact on participation and on people’s views about government more generally. Perhaps we will also find an erosion of confidence in institutions outside the political arena.

Declining trust and political engagement?

There is no doubt that politicians have become increasingly exercised by the public’s apparent lack of trust in the political process and a greater reluctance to go to the polls. In truth, Britain has never had that much trust in politicians and the political process, but trust has fallen further over the last 30 years. Back in 1986, only 38 per cent said that they trusted governments “to place the needs of the nation above the interests of their own political party”. By 2000, this had more than halved to just 16 per cent. After rising somewhat, it returned to a similar low in the immediate wake of the MPs’ expenses scandal of 2009 and, at 18 per cent, the latest figure is only a little better. While a degree of scepticism towards politicians might be thought healthy, those who govern Britain today have an uphill struggle to persuade the public that their hearts are in the right place. So it is perhaps little wonder that there are ever-growing demands for greater transparency in the political process, ranging from how much MPs are paid to the sources of party political funding.

People have also become less likely to accept that they have a duty to vote. Back in 1987, that year’s British Election Study found that 76 per cent believed that “it’s everyone’s duty to vote”. When we revisited the issue in 1991 only 68 per cent were of that view, falling to just 56 per cent by 2008. The figure has recovered somewhat in recent years and when we last asked the question in 2011, 62 per cent thought everyone had a duty to vote. But as our Politics chapter shows, each generation of new voters seems to be somewhat less likely than the previous generation to accept that it has a duty to vote, suggesting that over the longer term the proportion could well fall yet further still.

However, not all our trends point clearly towards declining political engagement. Although politics has always been something that only appealed to a minority, political interest is actually slightly higher now than it was in the mid-1980s. In 1986, 29 per cent said that they had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of interest in politics and the figure has remained at or around 30 per cent most years since then, and now stands at 36 per cent.[5] People are more likely now than in the 1980s to have signed a petition or contacted their MP, no doubt at least partly reflecting the increasing ease with which it is possible to do these things via social media. And, although a majority doubt their ability to influence what politicians do, they are no more likely to feel this now than they were in the 1980s – indeed, if anything, the opposite is the case. In 1986, for instance, 71 per cent agreed that “people like me have no say in what the government does”; now that figure is down to 59 per cent.

Political institutions

Despite this, there are signs of growing discontent with the way in which we are governed. Back in 1983 only 34 per cent per cent believed that “some change” was needed to the House of Lords. But by 1994 that proportion had already grown to 58 per cent, and it now stands at 63 per cent, even though in the interim most hereditary peers were removed from the chamber. In truth, as our 2011 survey showed, only 18 per cent favour having a House of Lords that is wholly or primarily appointed, as the chamber is now. Most think at least half the membership should be elected.

Equally, living in a more globalised and diverse world has done nothing over the long term to persuade us of the merits of our membership of the European Union (EU). True, Britain’s membership became increasingly popular during the 1980s, with the proportion who wanted Britain to stay in the EU rising from 53 per cent in 1983 to 77 per cent by 1991 (a point at which only 17 per cent wanted Britain to leave). However, that proved to be the high watermark of the European Union’s popularity in Britain. In 1993 we asked respondents a new question about Britain’s membership and, even then, more people (38 per cent) either wanted to leave the EU or to remain a member while reducing its powers than were keen to see European integration proceed even further (31 per cent). Now, however, Euroscepticism is firmly in the ascendancy, with a record 67 per cent wanting either to leave or for Britain to remain but the EU to become less powerful.

Meanwhile, as our Devolution chapter shows, although it is far from clear that Scottish support for independence has grown (despite the electoral success of the pro-independence Scottish National Party), there are signs of greater discontent south of the border about some of the apparent anomalies thrown up by the introduction of devolution in the late 1990s in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. For example, the proportion of people in England who think that Scotland gets “more than its fair share” of public spending has more than doubled from just 21 per cent in 2000 to 44 per cent now. Support for only allowing English MPs to vote on English laws, while always relatively high, has become even firmer. In short, the advent of devolution elsewhere in the UK seems to have raised questions about how England too should be governed, even though over half (56 per cent) of people in England think that England’s laws should continue to be made by the UK parliament.

The varying fortunes of other key British institutions

Politics and politicians are not alone in having seen their reputations harmed. Banks and bankers have suffered even more. Back in 1983, no less than 90 per cent thought that banks were “well run”; but in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, now just 19 per cent do so, probably the most dramatic change of attitude registered in 30 years of British Social Attitudes (see Table 0.1). The press too have been big losers. Now only 27 per cent think newspapers are well run compared with 53 per cent 30 years ago, a trend that might have been exacerbated by the phone hacking scandal that forced the closure of the News of the World in 2011, but which clearly began before then. Meanwhile, there have been more modest declines in the proportion who take a favourable view of both the police and the BBC (although our 2012 reading pre-dates the Jimmy Savile scandal that may well have done further harm to the BBC’s reputation).

Yet it would be a mistake to presume that we have witnessed a generalised loss of confidence in institutions. As we might have anticipated, this is not true of the NHS. More surprisingly perhaps, it is also not true of trade unions, perhaps because they are now less likely to be regarded as powerful institutions that are too ready to strike. Meanwhile, there is one other national institution whose reputation did appear to be on the slide for a while, but which now has made a substantial recovery. In 1983, as many as 65 per cent said it was “very important” for Britain to continue to have a monarchy. Little more than 10 years later that figure had slumped to 32 per cent and by 2006 was just 27 per cent. Numerous items of bad news for the royal family, including the break-up of the first marriage of the Prince of Wales and the subsequent death of his first wife, Diana, seemed to take their toll. Now, however, the figure has risen back up to 45 per cent, while only four per cent think keeping the monarch is “not important at all” and five per cent say “the monarchy should be abolished”. One of the country’s most traditional institutions seems to have recovered much of its lost public affection, demonstrating that the reputational decline of large public institutions is not an inevitable feature of modern Britain; indeed we might expect to see a further increase in support for the monarchy following the birth of baby Prince George Alexander in July 2013.

Reflections

As with public spending, we should be careful about presuming that any of the developments described in this section are simply the result of some inevitable process of individualisation. In fact, many are more likely to reflect the ways in which changing debates, controversies and events can influence the public mood. So, on Europe, for example, we have seen attitudes become more favourable and then less so again – perhaps in part reflecting Labour’s switch from being Eurosceptic to Europhile in the 1980s and then the Conservatives’ move in the opposite direction. Here, as with attitudes to welfare, political and policy debate appears to be entwined with public opinion. Equally, the decline in trust in politicians is likely at least partly to reflect particular events including the actions of politicians themselves – ranging from the allegations of sleaze in the 1990s to the MPs’ expenses scandal of 2009 – rather than from any more questioning outlook amongst the public or any more general loss of trust. There is certainly little evidence, despite much commentary to the contrary (for example, Puttnam, 2000) that people are markedly less willing to trust their fellow citizens. At 39 per cent, the proportion of people who say that “most people can be trusted” is little different now from the 43 per cent recorded when asked on a survey as long ago as 1981.

0 Comments