Handout: Utilitarianism and Business: Ford Pinto case

December 22, 2010

Utilitarianism and Business Ethics

Introduction

Welcome to philosophicalinvestigations – a site dedicated to ethical thinking (rather than one page summaries!!! Though I’m afraid I do add those at exam time – market pressures!). I hope you enjoy this case study which also has a powerpoint that goes with it. There’s plenty of other useful material on this site – case studies, handouts, powerpoints and summaries, and also I have written a number of books including best-selling revision guides and a useful book on ‘How to Write Philosophy Essays”.

If you’re worried about exams you might at least print out my strengths and weaknesses summaries under each moral theory. I deliberately quote only from my five favourite ethics books, visit our shop to find out which they are – because you might like to buy one of them to supplement your study. Of course, it’s important to quote the philosophers themselves in their own words – see my handouts, or for what academics say about them – see the key quotes section under the topic area of each moral theory. And if you’d like to blog on anything in the news send it to me – I’d be delighted to read it and – if it fulfils the criterion of good ethical thinking (!), post it!!!!!

Utilitarianism is a normative, consequentialist, empirical philosophy which links the idea of a good action to one which promotes maximum pleasure or happiness, found by adding up costs and benefits (or pains and pleasures). It has two classic formulations – Bentham’s hedonistic (pleasure-based) act utilitarianism and Mill’s eudaimonistic (happiness-based) rule utilitarianism. In this article we make some preliminary comments on Bentham and Mill before analysing a famous case in 1972 where utilitarian ethics seemed to cause a very immoral outcome – the Ford Pinto case.

Click here for a powerpoint presentation on the same subject containing a YouTube link for a ten minute documentary on this case.

Click here for a brilliant survey of the legal questions surrounding cost/benefit analysis – if you’re thinking of being a lawyer it’s a must read!

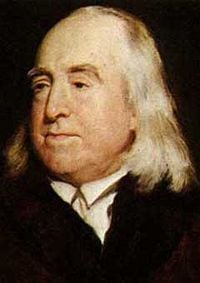

Bentham (1748-1832)

Bentham rejected Christianity and was influenced by David Hume (1711-76) and the French philosophe Helvitius, who argued that true justice was  synonomous with the good of the whole. He formulated the greatest happiness principle: “By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever, according to the tendency which it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question.”

synonomous with the good of the whole. He formulated the greatest happiness principle: “By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever, according to the tendency which it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question.”

• There is one good, pleasure, and one evil, pain.

• Human nature is naturally motivated by “two sovereign masters, pleasure and pain”. We are pleasure-seekers (hedonists). Other motives such as duty, respect, are irrelevant.

• The empirical calculation could be done with a hedonic calculus which allocates hedons of pleasure to different choices.

• Social goals should be fixed by aggregating personal goals in terms of maximising pleasure and minimising pain.

• The aim of government is to harmonize conflicting interests by passing laws with appropriate penalties for those who cause pain to others – hence modifying their behaviour.

Bentham became convinced that the British Government was influenced solely by self-interest rather than some idea of the common good. He came to argue for the abolition of the monarchy, universal male suffrage (not just linked to land), and rule by parliament as judge of the common interest.

John Stuart Mill (1806-73)

Mill’s version of utilitarianism was so different from Bentham’s that it almost seems that he rejects it. Mill was concerned to move away from what he once called a “swinish” philosophy based on base pleasures, to something subtler.

• Goodness was based on more than just pleasure, but on the virtue of sympathy for our fellow human beings, a concern for their rights and our duty to promote the common good.

• Pleasures were distinguishable between lower bodily pleasures and higher intellectual or spiritual pleasures – and if you wanted to know which was better ask someone who’d experienced both.

• Mill was suspicious of universal male suffrage, and advocated education for all as a key to graduating to the happy life.

• Mill was keen to see fairer distribution of wealth and income and rejected the extreme form of free market economics.

• Mill argues for a weak rule utilitarianism. We maximise happiness by obeying laws and social conventions which experience has shown promote the common good – such as respect for life, personal freedom and private property, or good manners and politeness. However, when two principles or rules come into conflict, such as the choice to lie to save my friend’s reputation, I revert to being an act utilitarian – making my decision based on a balance of outcomes – choosing that action which maximises happiness.

Business applications

Utilitarianism can be used in any business decision that seeks to maximize positive effects (especially morally, but also financially) and minimize negative ones. As with Bentham’s formulation, utilitarianism in business ethics is primarily concerned with outcomes rather than processes. If the outcome leads to the greatest good (or the least harm) for the greatest number of people, then it is assumed the end justifies the means. As Lawrence Hinman observes, the aim is to find “the greatest overall positive consequences for everyone” (Ethics, 136). This can be linked to the idea of cost-benefit analysis, so that “correct moral conduct is determined solely by a cost-benefit analysis of an action’s consequences” (Fieser, p7).

Just as John Stuart Mill objected to the coldest, most basic version of the theory, modern business ethicists point to utilitarianism’s limits for practical choices. For example, Reitz, Wall, and Love argued that utilitarianism isn’t an appropriate tool when outcomes affect a large number of separate parties with different needs or in complex processes whose outcomes and side effects can’t be readily foreseen, e.g., implementing new technology.

Utilitarianism suffers from the difficulty that costs and benefits may not be equally distributed. As Hinman comments “utilitarians must answer the question of whom are these consequences for?” (Ethics, 137). For example, if the UK government fails to regulate carbon emissions, acid rain falls on Sweden. If a tax is then placed on UK business to pay for this, the cost is borne by the UK taxpayer, the benefit is enjoyed by Sweden. There can be broad social costs, for example, of promoting unhealthy eating that are paid for by UK taxpayers in higher bills for health care, whereas the benefit (McDonalds profits) are enjoyed by employees and shareholders.

Such rules as “always pay your taxes” suffer from this problem, that the rich are actually subsidising the poor. Why should they? Mill would argue that we are concerned for others because of a general feeling of sympathy, which as a matter of fact, we all have. But suppose (as a matter of fact) I don’t share this feeling, then the rational utility maximising thing to do is to avoid paying tax as far as possible – move abroad, set up tax shelters, register my company in the lowest tax economy.

In applying utilitarian principles to business ethics, the cost-benefit analysis is most often used – it is a good decision making tool. Companies will attempt to work out how much something is going to cost them before taking action that should, ideally, result in consequences favourable to everyone. That would mean the company could make a profit, while the consumer benefited from their product. Hopefully, products are fit for purpose, safe, and give value for money. No business would attempt a project without evaluation of all relevant factors first, as well as taking other issues or risks into account that might jeopardise success. Ethical business practice, using utilitarianism, would thus consider the good and bad consequence for everyone the action would affect, treat everybody as having equal rights (at least in Mill’s weak rule utilitarianism), with no bias towards self, and would use it as an objective, quantitative way to make a moral decision.

CASE STUDY: Ford Pinto Case, utilitarianism and Cost Benefit Analysis:

This is an extract from a longer article, by Annie Lundy.

Read more: http://bizcovering.com/major-companies/applying-utilitarianism-to-business-ethics-the-ford-pinto-case/#ixzz18qFeyQRa

In applied business ethics, within the rule utilitarian theory of Mill, many principles exist which may be used to inform the morality of actions when analysing cost-benefit, or should be, if consequences are to favour more people overall. These include harm, honesty, justice and rights. So no harm should be done to others, people should not be deceived and their rights to life, free expression, and safety should be acknowledged. The argument here is that Ford abandoned these principles, abused the utilitarian theory to suit their needs, stayed within the laws of the time, but behaved unethically. The ‘utilities’ as a consequence, appeared to be money, and they used that to define the value of their needs against the value of human life.

Lacey (580-581) stated that:

“Ford pushed the federal regulators to put some price on auto safety…It was an agency of the U.S. government , the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) which arrived at this blood-chilling calculation, not the Ford Motor Company. But the way in which Ford took this government figure ($250,725) and used it for its own purposes carried a chill…”

So the Ford Pinto went on sale with dangerous design faults in the position of the fuel tank and nearby bolts, and the tendency for the fuel valve to leak in rollover accidents. Design and production was rushed and cost of the vehicle kept down to sell it at $2000. It sold well, until 1972 when four people died ,the first of many incidents stemming from the Pinto’s flaws, and many more followed, costing Ford millions in compensation. The cost-benefit analysis demonstrated an abuse of utilitarian principles, and the engineers were fully aware of the flaws, yet the company continued to sell the car as it was, without safety modifications. They “weighed the risk of harm and the overall cost of avoiding it.” Leggett, (1999).

The government figure, mentioned earlier, was made up of 12 ‘social components’ that included $10,000 for ‘victim’s pain and suffering’ and was meant to determine the cost to society for each estimated death. Ford decided to estimate 180 deaths, 180 serious burn injuries, 2100 vehicles lost, and calculated $49.5 million overall, a figure that would be a benefit to the company, if they put things right with the car. The estimated cost of doing so came to $137 million, for 11 million vehicles at $11 dollars per tank and $11 per unit for other modifications. So costs outweighed benefits by $87m and the value of human life was quantified as an economic commodity.

It also emerged that some evidence suggested the actual costs to correct matters were over-estimated and would have been nearer to $63.5 million. Though these did not equate to the benefits, there would seem to be a moral duty somewhere for a huge corporation like Ford, to bear the cost of $15 million. That way, utilitarian ethics, normative principles and the most good and positive consequences for most people overall would have resulted. There seems to be some form of justice in the way the benefits dwindled and the costs grew over the years, as lawsuits and penalties took millions of dollars from Ford. The company did nothing illegal in terms of design at that time; they took advantage of the cost-benefit analysis, ignored ethical principles and abused the moral aspects in utilitarianism. As Lacey (577) put it:

“The question is whether Ford and Iacocca [Executive vice president] exhibited all due care for their customers’ safety when balanced in the complex car making equation that involves cost, time, marketability and profit.”

Conclusion:

Utilitarianism, business ethics and the Ford Pinto case present a dilemma, as the theory appears to be one of moral strength and a good guideline for ethical business choice. In relating its consequential content to the Ford Pinto case, it would seem that the application of ethics had been dismissed in favour of profits, reputation and unethical practices. The theory cannot possibly be used to put a value on human life, as Ford attempted to do. The dangers in utilitarianism lie with the potential for abuse, and in abandoning the inherent principles, Ford demonstrated those dangers in action.

The decision not to rectify faults represented a denial of doing no harm, not deceiving others, justice and the rights to life and safety. Nor can the theory measure human suffering or loss, as Ford found, to its cost; it cannot predict consequences accurately or quantify benefits and harms, simply by applying a cost-benefit measure. In considering that the ends justify the means, another aspect of utilitarianism, and determining the pain of actions, volume and not ‘who’ suffers, has significance. In principle, the evaluation of good and bad consequences provides one way of ensuring that companies consider the morality of their actions, which may suggest that utilitarianism can be a positive influence for ethical business practice as long as the true costs can be accurately determined and the right value placed on human life.

References

Fieser, J. Ethics: Consequentialist Theories Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy2006. University of Tennessee at Martin. 24 April 2007

http://www.iep.utm.edu/e/ethics.htm

Hinman, L. M. Ethics: A Pluralistic Approach to Moral Theory: Chapter 5:

The Ethics of Consequences: Utilitarianism. 3rd Edition. Belmont, CA:Wadsworth: 2003

Lacey, R. Ford: Book Club Associates by Arrangement with William Heinemann Ltd. 1988

Leggett, C. The Ford Pinto Case: The Valuation of Life as it Applies to theNegligence Efficiency Argument. Law and Valuation Papers, Spring 1999 at Wake Forest University. 24 April 2007

http://www.wfu.edu/~palmitar/Law&Valuation/Papers/1999/Leggett-pinto.html

0 Comments