Handout: Situation Ethics

April 7, 2011

SITUATION ETHICS

“All you need is love.”

(John Lennon and Paul McCartney)

This article by Richard Jacobs is taken from the Villanova State University website. In it he helpfully describes situation ethics as “principled relativism” as, at the normative level of applying values, there are no absolutes, even though when considering the larger question of a supreme value there remains one principle which is non-negotiable – that of agape love. I have tried to edit out the more complex sentence structures in the original, and replaced the academic’s love of the word “agent” for “person”. For a more detailed treatment, it is recommend that you buy my book. PB

“Situation ethics” was a term Joseph Fletcher (1905-1991) adopted in 1966. Fletcher was an Episcopalian* priest, so this theory may be described as a Christian ethic (a form of Christian relativism, or liberal Christian morality). It is also reflected in the life of the German martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who rejected the absolute “thou shalt not kill” in order to participate in the Stauffenberg bomb plot of 1944, and the teachings of German theologians such as Emil Brunner. Situation ethics takes normative principles – like the virtues, natural law, and Kant’s categorical imperative – and generalises them so that we can “make sense” out of our experience when facing moral dilemmas. But situation ethics rejects any attempt to turn these generalisations into firm rules and laws, what Fletcher (1966) called a form of “ethical idolatry.”

Sometimes called “contextualism” or “relational ethics,” situation ethics maintains that the collective wisdom of the past can be used to guide our decisions now, but must be set aside if love requires something else. For situationists, love is the supreme principle, as John Lennon and Paul McCartney put it in the Beatles’ 1960s hit, “All you need is love.” Sometimes people ask ‘why are we studying a theory few people seem to follow these days”? But this is to misunderstand the role the theory still plays on Christian thinking. When a liberal Christian appeals to love as the supreme value – and against traditional church teaching on gay marriage, sex before marriage, or the lack of absolute rules on killing (abortion) or lying – then they are appealing to situationism.

The theory does beg some questions, (similar to questions we might pose of utilitarian ethics):

1. What do we mean by “love”?

2. Can love ever be purely concerned for another person?

3. Can we apply a general principle easily to calculate a “most loving outcome”?

4. Are we wise enough to guess likely results?

*Episcopalian is the name for the Anglican Church in America. Traditionally this has been the most liberal Christian denomination, and led the Anglican Church in being the first to ordain a gay bishop, Gene Robinson – an issue that has threatened to split the worldwide Anglican communion (and indeed, the Church of England in the UK). PB

The challenge

In Situation Ethics Fletcher addresses the difficult question how we apply moral principles to situations where we are forced to choose between two courses of action.

As was common during the anti-establishment years of the 1960s, Fletcher didn’t like the idea of following rules. Fletcher also rejected antinomian relativism (antinomian means literally “no principles”; Greek nomos means “law”). Fletcher rejected blind following of rules because he believed that absolute rules and laws demand unthinking obedience. Fletcher argued they only develop into elaborate systems of exceptions and compromises that eventually form additional rules and laws. These only serve to encourage people to invent clever new ways round these rules and laws.

Fletcher rejected antinomianism because he understood well the consequences of believing that no absolute rules and laws exist which are capable of governing all cultures in all places and for all times. The error in antinomianism is illustrated by William Golding’s (1959) novel about a group of English choir boys, Lord of the Flies. The nearest philosophy to antinomianism is Sartre’s existentialism.

Fletcher’s Middle Way between legalism and antinomianism

In place of legalism and antinomian relativism Fletcher places what he calls “situation ethics.” In real life situations people must acknowledge those traditional rules and laws (producing a less strict version of legalism) within which we seek to operate (so a less strict form of antinomian relativism). Fletcher’s common sense ethic avoided the extremes of legalism and antinomianism by recognising the remoteness of universal principles from actual conduct we can be certain about (e.g., lying is unethical) and, on the other hand, by filling the gap between such principles and difficult decisions which arise in everyday life (e.g., lying in this situation may be ethical).

While these rules and laws may assist in the process of ethical decision making, situationists modify these rules and laws if the situation requires. Why? Because our knowledge is far from certain. When human beings face situations where values conflict, we must make the decision for ourselves…and live with the consequences. Fletcher (following Martin Luther) calls this “sinning bravely”.

The fundamental issue for situationists concerns whether normative principles are not only valid in themselves, but also oblige all people, in all times and places. Are these principles universal? But existential ethics – which is called “antinomian” because it rejects absolutely the authority of rules and laws – is also problematic because it rejects absolutely the authority of rules and laws. In contrast, situation ethics endeavours to identify the idea of “good” based one one absolute principle (not a rule, notice), and to do what is ethical given the circumstances.

The problem posed by ethical rules and laws

Throughout human history, several writers have defined the “good” as “maximising happiness.” These theorists have not only speculated about what constitutes “true” happiness but also have laid down normative principles identifying what happiness requires in terms of human behaviour – such as Mill’s and Bentham’s Greatest Happiness Principle.

The ancient Greeks and Romans as well as theists and non-theists through the centuries have applied these normative principles in terms that approve some behaviour and condemn other behaviour. Telling the truth, fidelity and respect for life as well as others’ possessions seem to have stood the test of time in terms of specifying what constitutes ethical conduct. Similarly lying, adultery, murder and theft seem to have stood the test of time in terms of identifying conduct that most people would agree is unethical.

While situation ethicists agree with this widely-held conclusion, they question whether these normative principles are to be applied as commands ( as imperatives, for example, “never lie”) or, instead, as guidelines (as orientations, for example, as “wisdom” or “proverbs”) that we should use when deciding what to do. The situationists ask: should these norms, as generalisations about what we want, be regarded as intrinsically valid and universally binding on all human beings?

Take, for example, the ethical dilemma confronting the heroine of the Book of Judith reported in the Jewish Scriptures. The story, set in the time after the Kingdom of Assyria conquered Israel, occurred somewhere around 720 BCE.

Judith is a wealthy and pious widow. Diligent in prayer, obedient to the rules of mourning, observant of the dietary laws, and considered a pious and holy woman by all of the people who know her, Judith’s town is surrounded by enemy troops under General Holofernes. The general’s presumed intention is to destroy the town, its inhabitants, and their religion. To preserve the town, her fellow citizens, and their religion, Judith executes a daring two-part plan to murder the general. The first part of Judith’s plan involves a beauty “make over.” Then, Judith will make her way to the general’s camp where the guards will, in turn, escort Judith to General Holofernes. The second part of Judith’s plan is a bit more complex. It involves: (1) lying to gain the general’s confidence; (2) flattering and flirting with him; (3) getting the general drunk; (4) seducing him into believing that Judith will have sexual intercourse with him; and, lastly, (5) when the general slips into a drunken stupor, she will take his sword and behead him. Judith’s two-part plan unfolds exactly as she envisaged. To demonstrate the Israelite conquest of the Assyrians, Judith grasps General Holofernes’ bloody head by its hair, takes it outside the general’s tent, and holds it up for all to behold.

Is Judith a saint and heroine or a conniving murderer?

Richard Jacobs highlights Fletcher’s own description of his theory as “principled relativism” to explain Fletcher’s own argument that Situation Ethics is relativistic with one absolute at its heart- agape love. Under protest from academics, the syllabus writers took Situation Ethics out of the part labelled ‘relativism’, thus leaving something of a void for students – we simply do not study any pure relativist theory at A level- the one nearest to it, existentialism, is what Fletcher calls “antinomian” or anti-law. My own view is we should continue to discuss Situation Ethics in the context of relativism, whilst making some of the points Richard Jacobs makes below. However, as I argue in an article reproduced on this site, relativism is an ambiguous concept with at least three meanings, particular, consequentialist and subjective, and so needs handling with care.

Situationists note that this powerful story highlights much of what human beings confront in real-life moral dilemmas. The situation required Judith to set aside her personal ethics-“Thou shalt not kill” is the fifth of the 10 Commandments; “Thou shalt not lie” is the seventh- in order to save the people of her kingdom. Second, the situation illustrates how, when ethical principles come into conflict, we must choose the solution that will benefit the most people. This is not a strict utilitarian calculus that seeks to achieve the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest number of people but a pragmatic perception that there is no single set of infallible laws and rules to guide ethical decision making. What do exist are normative principles- like the 10 Commandments- that have stood the test of time and provide guidance. These normative principles, however, do not provide inerrant answers for people confronting complex ethical dilemmas.

Situation ethics highlights the important point that, in ethical dilemmas, circumstances do count. They not only can and should influence our decision-making process, but circumstances can and should also alter a person’s decision when warranted. Thus, situation ethics upholds the common sense observation:

“What is in some times and in some places ethical can be in other times and in other places unethical.”

What the situationists seek to avoid is the charge that they are ethical relativists at the level of norms. Situationists rightly point out that normative principles depend on a number of factors unique to particular instances. Thus, situationists conclude, normative principles-although helpful for understanding what ethics requires- do not transcend all situations as normative ethicists would like. For example, there are many situations in which we may understand clearly that lying, adultery, murder, and theft are unethical as principles but we may also understand with equal clarity that these prohibitions may not apply given the idiosyncratic circumstances in which we find ourselves. It is in this sense situation ethics is better called “principled relativism.”

Because situationists assert that relativity in ethics is found at the normative level, it does not therefore follow that the application of an ethical principle is inherently unethical at the level of conduct. As noted in the case of Judith and General Holofernes indicates, there are many instances when commonsense would dictate that telling a lie would not be unethical. For situationists, the principle isn’t relativized. What is relativized is the application of the principle in real life dilemmas where agents are confronted by a choice between two goods (or two evils). Thus, ethical norms are only “relatively obliging” as they provide one “absolute” to which all conduct is relative – the goal of the most loving outcome.

Explain the idea of “principled relativism”. Why is Fletcher’s theory still a middle position between antinomian existentialism and legalistic Kantian ethics?

The good that is to be sought

For centuries thoughtful people have attempted to define what the good is. While most definitions have pointed in the direction of that which brings about happiness (or Aristotle’s richer concept of human flourishing Greek eudaimonia), Moore (1903) claimed that most definitions specify the good in terms of itself, not what the good is in and of itself. “The good is the good” is equivalent to stating that “a car is a car.” So Moore argued that the good is an “unanalyzable predicate,” a word whose meaning is not able to be reduced to its individual components or properties.

For Fletcher, the application of the principle is what is important in ethics because, while the “good” itself is unanalyzable and incapable of definition, ethical behavior (the “goods”) are able to be analyzed and defined. The good is normative, neither ideal nor real, a principle guiding a decision. Human conduct is what translates a normative principle into an action which can be judged and defined as “ethical” (i.e., good) or “unethical” (i.e., not good).

Knowing what is “good”

When evaluating conduct before an action how are we to know that the course of conduct will in truth be good?

Situation ethics argues that the answer is found in the normative principle, “the good = love.” This is the first of the six fundamental principles (see table). Love (agapé, in Greek) is not a  feeling or emotion, but an attitude or a “disposition.” Love is a learnt attitude we use to solve ethical dilemmas (Stevenson, 1960). Whereas virtue ethics and natural law require that ethical principles be objective and universal, situation ethics takes the opposite approach. Circumstances determine what ethical principles demand.

feeling or emotion, but an attitude or a “disposition.” Love is a learnt attitude we use to solve ethical dilemmas (Stevenson, 1960). Whereas virtue ethics and natural law require that ethical principles be objective and universal, situation ethics takes the opposite approach. Circumstances determine what ethical principles demand.

Fletcher (1966) sees the situationist making a choice based on the ethical principles of his community. The situationist respects these principles because they do assist in clarifying the conflict in values posed by difficult moral choices. But the situationist is also prepared to compromise these principles or set them aside if love seems better served (1966, p. 26).

Fletcher argues that the commitment to some value functions as a starting point in the ethical decision-making process. This value- like love -cannot be “proven” in a strictly rational, empirical, or scientific manner. It has to be chosen. So a “leap” is required where we give up proving something to be either true or false and instead choose that value and make a commitment to it as one sets about making decisions in ethical dilemmas. He calls this theological positivism: a commitment to the value of love which is something like a conversion to love.

In situation ethics the principle of love as an attitude dictates concern for the good of people as something specified in various normative principles such as “respect for others and their property.” However, these principles don’t dictate what we are to do but instead depend on the circumstances. The social sciences and, in particular, those of anthropology and psychology, provide empirical data retrospectively so we can decide what is good conduct.

For a pdf of the table, click SIX FUNDA PRINCIPLES SE

The cases Fletcher discusses

Many people in the late 1960s and early 1970s applauded Fletcher’s insight into how ethics works in real-life dilemmas. Bishop John Robinson described it as “the only ethic for man come of age”.

Fletcher’s insight actually wasn’t novel. In fact, as early as the 5th century, St. Augustine was telling the members of his congregation in Proconsular Africa (Hippo Regius in Numidia) “love and do what you will.”

Unfortunately, situationists have seized upon a second unanalyzable predicate (Moore, 1903) to define the good, namely, “love.” Whether in its theological or secular sense, situationists assert that the “good” is “love” and this normative principle is what must guide ethical decision making. When confronting an ethical dilemma, we are required to do what love requires in order to bring about the greatest amount of good. The “good” is not particular conduct but the ontological (good-in-itself) principle invoked by a person who, in turn, applies it in particular situations.

It all depends upon what “love” means as a normative principle.

Before identifying specific criticisms of the theory consider three cases:

Case 1: The Irish Immigrants

More than 150 years ago, a group of newly-arrived Irish immigrants decided to make their way from Boston across North America to settle in the Minnesota where there was a bank managed by the Archbishop of St. Paul-Minneapolis, John J. Ireland, who personally guaranteed low-interest mortgages to poor Catholic immigrants who would farm the land

On a journey through Ohio the immigrants spotted some Indians. They knew Indians killed settlers, so the immigrants decided to hide in a forest somewhere along Lake Erie. The Indians tracked the immigrants. One woman was holding her baby who had been asleep, but was now awakening and about to cry. Instinctively the mother put her hand over the baby’s mouth because she knew that, if the baby made any noise, the Indians would immediately discover the immigrants and kill them. As the Indians drew nearer and nearer, the mother noticed that she was suffocating her baby.

If the mother kept her hand over her baby’s mouth she would kill her child. But if she took her hand away, the baby would cry and the Indians would kill the settlers. What should the mother do?

Case 2: The Bermuda Triangle Disaster

A Caribbean cruise ends in tragedy as the cruise ship sinks somewhere in the Bermuda triangle following a sudden hurricane. Fifty passengers survive along with the ship’s first officer. Afloat in a lifeboat, the officer tells the 50 survivors that the lifeboat has enough food for 20 people for 10 days. In that time, the 20 probably could row to safety at the nearest shore.

The ship’s officer also points out that the ship was miles off course when it sank and the captain failed to send out an SOS. The ship’s lifeboats were not equipped with the latest GPS technology. So it is quite likely that everyone will starve to death if they stay put because it is equally unlikely that a search plane will find the 50 who survived the capsize within four or five days

What should the 50 survivors do? Throw the 30 most frail survivors overboard so that the 20 most healthy can row to land and live? Or, should the 50 do nothing knowing that, in all likelihood, all 50 will die?

Case 3: The Apartment Fire

Someone heads to her best friend’s apartment. As this individual turns the corner, she sees that the apartment is on fire. Racing to the scene and standing outside of the apartment, she knows with absolute certainty that two people are inside: her best friend who is a hair stylist and her best friend’s lover who is a skilled in vitro neurosurgeon. Judging from the ferocity of the flames, she is pretty certain that she will have just enough time to dash into the house and rescue only one of the two persons in the apartment. Who should she rescue first?

According to situation ethics, the principle of “love”-not ethical rules or laws or, even, what one thinks best- tells us what we ought to do. In the first situation, the loving thing is for the mother not to suffocate her baby and for the Indians not to murder the immigrants. In the second situation, the loving thing is for members of the Coast Guard to rescue the 50 survivors. In the third situation, the loving thing is to rescue both your friend and you friend’s lover. However, in all three cases, it is not possible to do what love requires.

So, we must now decide upon a course of conduct which will specify who we will help.

In Situation Ethics, Fletcher (1996) argues that the following general principles would enable an agent to arrive at an ethical decision: a) help the person whose need is greater; b) perform the action that helps the greatest number; and, c) help the person who is more valuable.

Applying these principles to the first case, the second principle is especially pertinent. The ethical decision is for the mother to suffocate her baby because the Indians may then give up their search for the immigrants if they offer no further clues of their presence in the forest. In the second case, the second principle also applies. Thus, the ethical decision is to jettison the 30 weakest people overboard so that the fittest 20 survive. Otherwise, everyone will die. In the third case, the third principle is especially pertinent. The ethical decision is to rescue the surgeon because this person can provide greater and more valuable help to more people than the hair stylist will ever be able to provide.

Because situationists think that only one thing is ethical, to love other people, all other considerations are irrelevant. It is this logic, which critics find objectionable -everything is permitted (which can include killing, jealousy, generosity, stealing, etc., because none of these actions are ethical or unethical in their own right). According to Fletcher, these actions become unethical only if we do them out of hatred or indifference; likewise, these actions are ethical if performed out of love.

The critics

These cases provide the context for considering the arguments put forward by those who criticize situation ethics.

Adler (1996) argues that the solution offered by situationists is “unsound” because in appealing to love and to love alone, the solution is totally ignorant of the teleological ethics of common sense which has already staked out a more tenable middle ground. For example, Aristotle notion of the “Golden Mean” argues for us to make specific determinations about what virtue requires in different situations.

Other critics argue that in theory, situation ethics operates according to an absolute norm or standard: the selection of an absolute, but non-legalistic, flexible application of the standard in each and every situation. The goal is to apply this absolute standard in the particular situation rather than to use a rule or law that fits difference circumstances. In this sense situation ethics is based upon a faulty premise.

Religious leaders and Christian fundamentalists argue against situation ethics because it maintains that each situation demands its own standard of ethics. Theoretically we may commit adultery, abortion, theft, drunkenness, and use illegal narcotics and drugs as long as those who engage in the conduct do so according to the principle of love and as long as no one is hurt by it. An agent may lie, if one believes it appropriate to spare the feelings of someone or to be socially acceptable. An agent may steal, if the act is perpetrated to help a needy person. Taking this idea to its logical conclusion, there is in fact no action that we cannot perform if, in one’s judgment, the action is for a good cause and the agent has the proper motive in performing it.

Then, there’s human nature. Often people will take a good insight-and, in this instance, the good idea at the heart of situation ethics-and press beyond that good idea to twist it into a rationale justifying subjectivism and ethical egoism. Teenagers are particularly prone to this behavior as is any person who seeks to justify conduct that is proscribed by one’s society, religion, or upbringing.

Consider the following cases:

Case 4: Living Together

Jack and Susie have finally confessed to their parents about the fact that they have been living together. Both sets of parents are shocked and angry. But, Jack and Susie argue, “We only wanted to make sure we were meant for each other. You know that so many marriages end in divorce. Can’t you understand we only want to do the most ‘loving’ thing so that neither of us would be hurt?”

Case 5: The Affirmative Pregnancy Test

Following weeks of worry, Marion has just received an affirmative on her pregnancy test. However, Marion is a full-time graduate student who is working a part-time job in order to make ends meet. So she thinks: “I’ll have an abortion!” And, then, as if to justify her decision, Marion tells herself: “It wouldn’t be fair to bring an unwanted baby into an already over-populated world.” Furthermore, thinking about her busy schedule, Marion is sure that she won’t be able to give the baby the attention or time it would deserve. Lastly, Marion considers the fact that the baby’s father is someone she barely knows, the baby having been conceived during a “one night fling” with a fellow she met in a singles’ bar. Marion concludes that the loving and most practical thing for everyone involved in this dilemma is to procure an abortion.

Were anyone to tell Jack and Susie or Marion that they had no right to make the decisions which they did, Jack and Susie or Marion might well accuse those persons of imposing their personal standards upon her. Since Jack, Susie, and Marion are situationists, each believes they are completely capable of making “loving” decisions in the ethical dilemmas they confront.

However, the problem is that situation ethics puts forward the normative principle of “love” without providing any definition that would indicate what love requires of us as we confront ethical dilemmas. Denouncing legalism and rejecting any rigid moral rules, situationists assert that the only necessary thing is to consider the situation and what seems best from our point of view. For situationists, this is the most “loving” decision. Critics argue that the flaw evident in the case of Living Together and the case of The Affirmative Pregnancy test is that the agents have confused an unanalyzable and vacuous secular ethic of love with a substantive theological ethic of love as defined by God and set out in the Bible and in Church teaching. So to sum up:

1. Agape love, the love of a stranger that is unconditional, generous and sacrificial (as in the Good Samaritan parable) is a very high standard very few can attain. Even parents struggle to love their own children unconditionally.

2. In the Bible it is only possible through the power of the Holy Spirit. So by definition it is impossible for atheists.

3. It suffers from the problem of calculation (as does it’s close sister, utilitarianism).

4. It seems to neglect the wisdom of years of collective human experience which reflects itself in rules and conventions of morality. This is William Barclay’s central point in his book Ethics in a Permissive Society. John Stuart Mill argued something very similar – that rules arise as landmarks and signposts that (as signposts usefully do), help us on our way. The situationist is like the car driver navigating on a dark night where the road signs are invisible and relying on an instant intuition when he or she arrives at a roundabout. The more unfamiliar we are with the road, the harder the judgement. We almost inevitably get lost.

Conclusions

Situation ethics says that we must make ethical judgments within the context of the situation. There are no fixed ethical rules and laws which apply to each and every moral dilemma as no two situations are identical, and because the theory stresses personalism (one of Fletcher’s four working principles together with positivism, pragmatism, and relativism), no two humans are identical either. Situation ethics holds that there is one normative principle- the ethic of love -that we can apply in ethical dilemmas on a universal basis.

Situation ethics does not attempt to abstract ethically relevant features from particular cases and to apply them to other similar cases, as do virtue ethicists, natural law theorists, and absolutists. Instead, situation ethics leaves it up to us who is to evaluate the ethical choices available within the context of the entire situation as we apply the ethical principle of love. At the same time, situation ethics insists that this ethical principle can only be understood appropriately within the particulars of the situation.

Critics argue that while situation ethics provides a valuable insight into the nature of ethics and how we solve real life ethical dilemmas, the theory can be pushed to extremes which would allow just about any conduct. To be logically consistent, the critics maintain that ethics cannot condone immoral behaviour as ‘moral’.

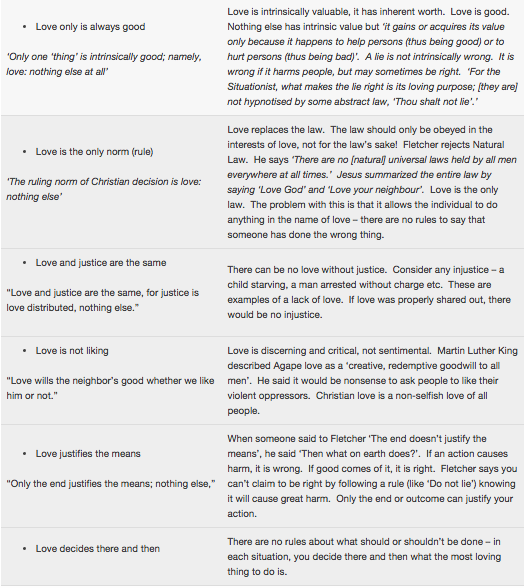

Six fundamental principles: (don’t confuse with the four working principles PPPR)

I would learn proposition 1, 3, 5 and 6. PB

First proposition

Only one thing is intrinsically good; namely love. Fletcher (1963, pg56)

Second proposition

The ruling norm of Christian decision is love. Fletcher (1963, pg69)

Third proposition

Love and Justice are the same, for justice is love distributed. Fletcher (1963, pg87)

Fourth proposition

Love wills the neighbour’s good, whether we like him or not. Fletcher (1963, pg103)

Fifth proposition

Only the end justifies the means Fletcher (1963, pg120)

Sixth proposition

Love’s decisions are made situationally. Fletcher (1963, pg134)

Something to think about:

“The true opposite of love is not hate but indifference. Hate, bad as it is, at least treats the neighbour as a thou, whereas indifference turns the neighbour into an it, a thing. This is why we may say that there is actually one thing worse than evil itself and that is indifference to evil. In human relations the nadir of morality, the lowest point as far as Christian ethics is concerned, is manifest in the phrase, “ couldn’t care less.’ Joseph Fletcher

0 Comments