Handout – The Problem of Evil & Theodicies of Augustine and Irenaeus

January 8, 2018

The Problem of Evil

The existence of bad or evil things isn’t hard to explain for non-theists—human beings and the world are imperfect—but they are hard to explain for classical theists because of their belief in the perfect goodness of God. JL Mackie explains it this way:

In its simplest form the problem is this: God is omnipotent; God is wholly good; and yet evil exists. There seems to be some contradiction between these three propositions, so that if any two of them were true the third would be false. But at the same time all three are essential parts of most theological positions: the theologian, it seems, at once must adhere and cannot consistently adhere to all three. (Mackie, 1955, page 200)

The Inconsistent Triad

The Problem – God is all-good, powerful, and knowing (the triad of God’s qualities) and yet there is evil. Thus either God can’t do away with evil—in which case God is not all-powerful; or God won’t do away with evil—in which case God is not all good. We can distinguish between:

a) The logical problem of evil – God and evil are incompatible or inconsistent; and

b) The evidentiary problem of evil – evil counts as evidence against the existence of God.

Response to the problem – Theists have articulated defences, but generally dismiss theodicies (complete explanations for evil.) A defence is easy, you just need to show that it is rational to believe in God and evil simultaneously. A theodicy is harder to justify: it must show how evil fits into God’s plan. Most theologians think that the best we can do is to show that evil and the the existence of God are compatible, but they don’t believe they can completely explain evil. In order to defend the rationality of religious belief—to offer a strong defence—philosophers/theologians try to provide reasons for the existence of evil. These include two theodicies which give rather different justifications for evil.

Evil results from Free Will – Augustinian Theodicy

The argument here is that a world with humans and the evil that results from their free will is better than one without humans even if that world had no evil. War, murder, torture, etc. are worth the price of the positives that derive from human free will. Moreover, God cannot be held responsible for the evil which results. The key thinkers who have argued this include St Augustine (354-430) and St Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274).

St Augustine wrote extensively against the heresy of Manichees. A key belief in Manichaeism is that the powerful, though not omnipotent good power (God), was opposed by the eternal evil power (devil).

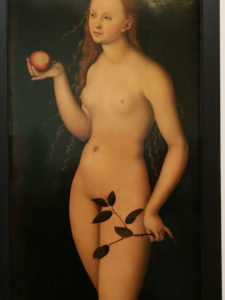

Augustine of Hippo bases his theodicy (defence) on a reading of key Biblical passages: Genesis 3 and Romans 5:12-20. Augustine’s is an attempt to solve the evidential problem of the existence of evil: evil must have come from somewhere. Genesis 3 is the story of Adam and Eve and their ‘Fall’ in the Garden of Eden, whereby the snake convinces the woman to eat the forbidden fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. The woman picks the fruit, and passes some to Adam. Because of their disobedience God has them evicted from the garden with a curse: the woman will experience pain in childbirth and the man will lord it over the woman and have to till the ground to rid it of the unruly influence of nature (the weeds begin to grow).

16 To the woman God said,

“I will make your pains in childbearing very severe; with painful labor you will give birth to children. Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you.”

17 To Adam he said, “Because you listened to your wife and ate fruit from the tree about which I commanded you, ‘You must not eat from it,’

“Cursed is the ground because of you; through painful toil you will eat food from it all the days of your life.18 It will produce thorns and thistles for you, and you will eat the plants of the field.19 By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return.” (Genesis 3:16-19)

In Romans 5 Paul picks up this idea of humankind’s fall away from God’s grace and blessing, and describes the Christian belief that Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross redeems us from the effects of the disobedience of Adam and Eve. In his self-sacrifice Jesus has made available the gift of righteousness, taking the penalty for our disobedience on himself.

These are the main points of Augustine’s theodicy:

- God is perfect. The world he created reflects that perfection.

- Humans were created with free will.

- Sin and death entered the world through Adam and Eve at the Fall in Genesis 3, and their disobedience in taking and eating the ‘fruit of the knowledge of good and evil’.

- “Evil has no positive nature; but the loss of good has received the name evil” (Augustine, City of God).

- Adam and Eve’s disobedience brought about ‘disharmony’ in both humanity and Creation.

- The whole of humanity experiences this disharmony because we were all ‘seminally’ present in the loins of Adam.

- Natural evil is consequence of this disharmony of nature brought about by the Fall.

- God is justified in not intervening because the suffering is a consequence of human action.

Notice that central to Augustine’s theory is that of ‘privation’ – evil is not a substance in itself, but rather it is a deprivation or an absence of something. Augustine uses the analogy of blindness – blindness is not an entity but the absence of sight. For Augustine, evil came about as a direct result of the misuse of free will which made us in our own turn blind, and weakens our ability to do active good without God’s help. It’s worth reading Augustine’s words in full, where he explains that darkness is the privation of light, and that the divine artist has ordered everything, so by analogy, just as a great singer will pause and the pauses are designed to render the beauty of the song more complete. So God does not create our vices, but orders, or perhaps we say, permits them to occur.

For Scripture did not say that God made the darkness. God made the forms, not privations that pertain to that nothing out of which all things were made by the divine artist. But we understand that he ordered these privations when it is said, “And God divided the light and the darkness,” 18 so that even these privations are not without their order, since God rules and governs all things.

Thus when we sing, the moments of silence at certain and measured intervals, although they are privations of sounds, still are well ordered by those who know how to sing and they contribute something to the sweetness of the whole melody. So too, shadows in a painting highlight certain things and are pleasing, not by their form, but by their order.

For God does not make our vices, but he still orders them when he puts sinners in that place and forces them to suffer what they deserve. This is what it means for the sheep to be placed on the right and the goats on the left.

Thus he both makes and orders the very forms and natures, but he does not make, but only orders, the privations of forms and the defects of natures. Thus he said, “Let there be light, and the light was made.” 50 He did not say, “Let there be darkness, and darkness was made.” One of these he made; the other he did not make.

But he ordered both of them, when God divided the light and the darkness. Thus, since he is their maker, individual things are beautiful, and since he orders them, all things are beautiful. (Augustine, Against the Manichees, Book2, Chapter 5)

It’s important to notice that all suffering is therefore a consequence of this abuse of free will. God is not responsible for these evils, as “God does not make our vices, but he still orders them when he puts sinners in that place and forces them to suffer what they deserve.’ According to Augustine, evil includes natural evil, such as earthquakes and famines, as well as moral evil which can be attributed directly to human beings. Natural evil has come about through an imbalance in nature brought about by the Fall. Humans are therefore responsible for both moral and natural evil.

Finally, God’s everlasting love for the world is demonstrated through the reconciliation made possible through Jesus Christ.

“For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him.”John 3:16-17

A modern advocate of Augustine’s view can be found in Alvin Plantinga (God, Freedom and Evil, 1974) who claimed that for God to have created a being who could only have performed good actions would have been logically impossible. This view was later criticised by Anthony Flew and J.L.Mackie, who both argue that God could have chosen to create “good robots” who still possessed free-will.

Criticism of Augustine’s Theodicy

Augustine argues that the sin of Adam and Eve in choosing to eat the fruit of the garden resulted in a curse which is passed down through human reproduction to every human being.

Augustine held that there was a state of ignorant bliss in the Garden of Eden which was unbalanced by the Fall. Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection gives a completely different account of human nature, which has evolved over millenia to exhibit both good characteristics (what Richard Dawkins calls ‘the altruistic gene’) and self-centred characteristics (what the Bible calls ‘sin’).

However, we might argue God can be held responsible for the system by which the natural world works, He should be held responsible for the suffering that his system causes. Augustine’s theodicy puts all the blame on the first humans, Adam and Eve, and yet all suffer. We might ask: why should people suffer for the misdemeanours of past generations? Moreover, Augustine seems to fail to mention anything about God’s omniscience – if God foreknew the Fall of humankind and also designed a consequence of suffering for both Adam and Eve, surely this continues to be a challenge to the idea of God’s omnibenevolence (God’s perfect love). What human being would decree permanent suffering for his or her children? Augustine also makes much of the idea of a literal hell – as part of Creation. Therefore God must be directly responsible for creation, and therefore must have foreseen the need for punishment.

So we can answer that free will is not worth all the misery that ensues from free choice, and surely the omniscient (all-seeing, all knowing) God would have foreseen this evil and stopped it happening?. Why did an omnipotent God not create humans with the freedom to do bad things, but who never do them because our wills are always tuned to choose right?

Moreover, free will, if it even exists, only accounts for moral evil (evils attributed to free will like murder, rape, etc.) but not natural evil (earthquakes, floods, disease, etc) which have nothing to do with free will. Natural evil cannot be attributed to the event of the Fall of Adam and Eve, but rather to something faulty in the design of a world which surely a good designer would have avoided, a point David Hume notes in his attack on the teleological (design) argument for God’s existence.

Evil is Necessary for the Development of Moral Character

In a world without “trials and tribulations” we wouldn’t develop our moral characters or test and prove the strength of our souls. Such a world, so this argument goes, wouldn’t elicit such good qualities as generosity, courage, kindness, mercy, perseverance, creativity. These qualities are forged out of suffering and difficulty.

Irenaeus’ Theodicy

St Irenaeus presents a contrasting view to Augustine, whereby evil has a positive benefit in teaching us to develop moral characteristics.

Irenaeus (c130-200) developed a theodicy of what we can describe as ‘soul making’. His theodicy is more concerned with the development of humanity and the moral character of human beings.

Irenaeus distinguished between the ‘image’ and the ‘likeness’ of God. Adam had the form of God but not the content of God. Form here suggests potential, and content implies the completed, finished, full characteristics of God the Father (generosity, goodness, love). Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden because they were immature and needed to develop, so that they might grow into the likeness (content) of God. They were the raw material for a further stage of God’s creative work.

The fall of humanity is seen as a failure within this second phase of becoming more like God in content.

Suffering is a necessary part of God’s created universe – it is through suffering that human souls are made noble. The world is a ‘vale of soul making’.

One of the ways in which this ‘test’ is carried out is through faith. God’s purpose cannot easily be discerned, but believers continue to believe despite the evidence. This faith becomes a virtue. John Hick calls this lack of understanding an ‘epistemic distance’.

To summarise Irenaeus’ Theodicy:

- Humans were created in the image and likeness of God.

- We are in an immature moral state, though we have the potential for moral perfection.

- Throughout our lives we change from being human animals to ‘children of God’.

- This is a choice made after struggle and experience, as we choose God rather than our baser instinct.

- God brings in suffering for the benefit of humanity as a direct consequence of human free will.

- From it we learn positive values, and about the world around us.

Suffering and evil are:

- Useful as a means of knowledge. Hunger leads to pain, and causes a desire to feed. Knowledge of pain prompts humans to seek to help others in pain.

- Character building. Evil offers the opportunity to grow morally. If we were programmed to ‘do the right thing’ there would be no moral value to our actions. ‘We would never learn the art of goodness in a world designed as a complete paradise’ Swinburne.

- A predictable environment. The world runs to a series of natural laws. These laws are independent of our needs, and operate regardless of anything. Natural evil is when these laws come into conflict with our own perceived needs.

There is no moral dimension to this. However, we can be sure of things in a predictable world governed by what Aquinas later calls the ‘eternal law’ which is partially revealed to us in the natural law (which he develops into a fuller moral theology) and the divine law (the Bible).

Heaven and hell are important within Irenaeus’s Theodicy as part of the process of deification, the lifting up of humanity to the divine. This process enables humans to achieve perfection.

Irenaeus never developed his theodicy fully but his ideas were later taken up by Friedrich Schleirmacher (1768-1834) and more recently by John Hick(1922-2012), who has argued:

“Human beings were brought into existence as intelligent creatures endowed with the capacity for immense moral and spiritual development. They are not the perfect pre-fallen Adam and Eve of the Augustinian tradition, but immature creatures, at the beginning of a long process of growth”. John Hick (1966:249)

John Hick’s theology shares many aspects of Irenaeus’. Both believed in a vale of soul-making and that everyone would eventually be saved.

According to Hick, the divine intention in relation to humankind is to bring forth perfect finite personal beings by means of a “vale of soul-making” in which humans may transcend their natural selfishness by freely developing the most desirable qualities of moral character and entering into a personal relationship with God.

Any world, however, that makes possible such personal growth cannot be a hedonistic paradise whose inhabitants experience a maximum of pleasure and a minimum of pain. Rather, an environment that is able to produce the finest characteristics of human personality – particularly the capacity to love – must be one in which

“There are obstacles to be overcome, tasks to be performed, goals to be achieved, setbacks to be endured, problems to be solved, dangers to be met” (Hick 1966: 362).

A soul-making environment must, in other words, share much in common with our world, for only a world containing great dangers and risks, as well as the genuine possibility of failure and tragedy, can provide opportunities for the development of virtue and character. A necessary condition, however, for this developmental process to take place is that humanity be situated at an “epistemic distance” from God (a knowledge gap, similar in Aquinas’ thought to the gap that exists between the eternal law in the mind of God and the revealed natural law and divine law, which are partial, incomplete).

On Hick’s view, in other words, if we were initially created in the direct presence of God we could not freely come to love and worship God. So to preserve our freedom in relation to God, the world must be created religiously ambiguous or must appear, to some extent at least, as if there were no God. And evil, of course, plays an important role in creating the desired epistemic distance.

Problems with Irenaeus’ Theodicy

Irenaeus and Hick have argued that everyone goes to heaven. This would appear unjust, in that evil goes unpunished, and contradicts the view of Augustine that God orders punishment as a logical consequence of sin. Morality also arguably becomes pointless. This is not orthodox Christianity. It denies the Fall, and Jesus’ role is reduced to that of moral example rather than the sacrifice that makes our redemption possible.

Why should ‘soul making’ involve suffering? The ‘suffering is good for you’ argument seems unjust, especially in the suffering of innocents. Hume was critical: ‘Could not our world be a little more hospitable and still teach us what we need to know? Could we not learn through pleasure as well as pain?’ asks David Hume. Swinburne argues that our suffering is limited, by our own capacity to feel pain, and by our lifespan.

Can suffering ever be justified on the grounds of motive? Suffering does not sit easily with the concept of a loving God. It seems difficult to justify something like the Holocaust with the concept of ‘soul making’.

If the moral character development argument is combined with the free will defence then we have given the best account of evil possible. This is not a theodicy—a complete explanation—but a defence—a partial explanation. We could even add that since there is another world evil here is no big deal anyway. That is, all this pain will be insignificant when we all enjoy eternal bliss. Of course, even if we can overcome the problem of evil that doesn’t mean the theistic story is true.

Three Problems Remain

At least three basic problems remain in our attempt to reconcile evil and an all good, all-knowing and all-powerful God.

1) Why doesn’t God intervene to prevent extreme cruelty—such as the abuse of an innocent child? The free will defence is implausible here.

2) Why is there so much human suffering? Do we really need all these hurricanes and diseases? Do we really need to develop our characters by, for example, accidentally killing children or suffering from cancer? And even if we need to occasionally die in childbirth or from cancer, couldn’t we have fewer cases of this evil?

3) Why do non-human animals suffer so much? They don’t have freedom or need to develop their moral characters, yet they suffer. If you look at the entire world, and the entire history of the world, does the evidence suggest that it is the product of a good, all-powerful, deity? Or does the evidence suggest the opposite? At the very least, doesn’t evil provide evidence against the existence of such a God? Of course, it may.

sources; Scandalon, Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy

Against the Manichees copyright Catholic University of America Press

0 Comments