Handout: Plato, the Cave and Knowledge

October 29, 2012

Plato, Knowledge and the Cave

This handout is adapted from Andrew Capone, A Workbook on Philosophy of Religion (Peped, 2018)

A. Allegory of the Cave

What is Knowledge?

In Republic, Plato explores the nature of knowledge and how only reason (episteme) can lead to true knowledge (doxa) as  experience will only give us changing opinion.

experience will only give us changing opinion.

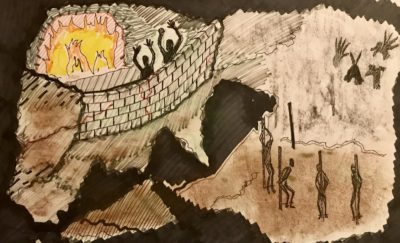

Plato’s allegory of the cave appears in The Republic. Each aspect of the allegory represents something in the real world.

We need to explain each of the symbols of the cave: The cave wall, the prisoners, the shadows, the puppets, the free prisoner, the jagged path, the sun.

The Cave wall represents the reality we see, touch and hear every day – the world of experience.

The Prisoners represent all those who never get beyond sense experience.

The Shadows represent the superficial or partial truth.

The Puppets – between the fire and the prisoners there is a parapet, along which puppeteers can walk. The puppeteers, who are behind the prisoners, hold up puppets that cast shadows on the wall of the cave. The prisoners are unable to see these puppets, the real objects, that pass behind them. What the prisoners see and hear are shadows and echoes cast by objects that they do not see.

The Free Prisoner represents anyone who takes the journey to Enlightenment – who seeks after truth, goodness and beauty.

The Jagged Path represents the hard journey to find ultimate truth, It is the journey of the philosopher.

The Sun is the ultimate source of the Form of the Good – of truth and beauty.

The Free Prisoner

Plato’s Cave by Edwin Blanco-Arnesto

In the Allegory of the Cave Plato identifies the free prisoner as the philosopher.

Men would say of him that up he went and down he came without his eyes; and that it was better not even to think of ascending; and if any one tried to loose another and lead him up to the light, let them only catch the offender, and they would put him to death. Plato, Symposium

What does the journey up the jagged path represent? Plato suggests that if the prisoner were led to the entrance to the cave he would have to struggle up the steep and jagged rocks to climb out of the cave. This journey out of the cave by the prisoner is the journey of the new philosopher to enlightenment. Just like the released prisoner, the new philosopher struggles to take in his new world view. It is a painful process thinking in new ways. This is clearly represented in the ascent out of the cave up the steep and jagged rock path.

“Suppose… that someone should drag him… by force, up the rough ascent, the steep way up, and never stop until he could drag him out into the light of the sun.” The prisoner would be angry and in pain, and this would only worsen when the radiant light of the sun overwhelms his eyes and blinds him”. (Republic 519a)

“Slowly, his eyes adjust to the light of the sun. First he can only see shadows. Gradually he can see the reflections of people and things in water and then later see the people and things themselves. Eventually, he is able to look at the stars and moon at night until finally he can look upon the sun itself (516a).”[3] Only after he can look straight at the sun “is he able to reason about it” and what it is (516b).

Why is it significant that the free prisoner does not recognise what he sees when he leaves the cave? This section of the analogy is very important as the outside world represents the World of Forms. It is the sun that provides the true shape and colour in the analogy and so the sun represents the Form of the Good (FoG). But initially its light is blinding. Plato is stating that the FoG gives all of the other Forms their shapes. This is the goal of every philosopher; to gain intimate knowledge of the FoG and realise that the physical world (or the cave) is not true reality. It should also be noted that the fire in the cave is a superficial sun. The fire that burns only gets its energy from wood which comes via the sun.

B. The Theory of FORMS

The Theory of Forms is an attempt to solve the Problem of Universals and the Problem of Change: how can we have an abstract idea (knowledge) of universal categories when we only observe individual things? And if everything is changing how can we define its essence?

FORMs and Particulars

The white knight space-saver bed is only one of many instantiations of a bed. So what makes ‘bedness’?

In Republic, Plato gives the example of the idea of a bed and an example of a bed.

And what of the maker of the bed? Were you not saying that he too makes, not the idea which, according to our view, is the essence of the bed, but only a particular bed?

What is the relationship between ideas and particulars? The idea is in a sense the ideal or ideal FORM. The particular will always be an imperfect representation of this ideal – a shadow of it if you like. But the ideas or ideals move us upwards ina kind of pyramid at the top of which lie concepts of absolute truth and beauty – where the particulars find their ultimate reflection.

Why does the example of the idea of bed (and other things that are physically instantiated) cause problems for the theory of FORMs compared with the idea of justice? Because a bed is a physical thing and there are many individual types of bed which nonetheless have to be reflected in some essential absitract quality of bed – the question (and problem) is – what is that essential quality? Whereas justice is an abstract idea and therefore easier to ‘idealise’.

The Fool and the Philosopher

FORMs are abstract and eternal ideas. We recognise the FORMs in the temporal examples we encounter in this world. The FORMs are the essence of the thing we are encountering. The Essential FORM of Goodness gives life to all other FORMs. For example, the fool sees many different trees, but the philosopher sees many examples of the true FORM of tree.

Question: Give an example of the essence of love,

Answer: For Plato goodness and beauty are the essence of love. “Love is always directed towards what is good, indeed that goodness itself is the only object of love. When we love something, we are really seeking to possess the goodness which is in it.” Lydia Amir

The Forms are necessarily perfect and immutable, and by definition paradigmatic of that which they constitute. They do not change and alter in the way of the physical world; for if they did they would no longer be perfect, and cease to be anything but yet another example of that which they truly are. Plato argued that “because the material world is changeable it is also unreliable,” and used this to build his conception of worthy knowledge coming only from an understanding of the Forms, and not their tangible instantiations. No one has, for example, drawn the perfect triangle, for the drawing of such a thing would require a level of precision the infinite reducibility of spatial measurements would render impossible. This does not, of course, mean that the perfect triangle does not exist: when we attempt to draw a triangle we are guided by our understanding of the Form of Triangle-ness, not of the imperfect demonstrations we have seen drawn before us. The limits of the material world do not inhibit the Forms; the Forms are necessarily perfect, and the Form of Triangle-ness is perfectly triangular. (Philosophy News)

The Nature of the FORMs

In Cratylus, Plato discusses the nature of knowledge and how we can distinguish between examples and true knowledge. The essence is apart from the many examples.

For neither does every smith, although he may be making the same instrument for the same purpose, make them all of the same iron. The form must be the same, but the material may vary, and still the instrument may be equally good of whatever iron made, whether in Hellas or in a foreign country; there is no difference.

Later, Plato argued that knowledge of things changes over time, so no true knowledge can be gained from physical examples of things.

But if the very nature of knowledge changes, at the time when the change occurs there will be no knowledge, and, according to this view, there will be no one to know and nothing to be known: but if that which knows and that which is known exist ever, and the beautiful and the good and every other thing also exist, then I do not think that they can resemble a process of flux, as we were just now supposing.

Exercise: How does Plato distinguish between the FORM of an object and a material example?

“The Platonic idealist is the man by nature so wedded to perfection that he sees in everything not the reality but the faultless ideal which the reality misses and suggests”. George Santayana · (Santayana, G. (2010). Egotism in German Philosophy. Charleston: Nabu Press.)

C. Evaluating Plato

Influences on Plato

Plato’s theory was built on many ideas that circulated around his time, primarily from Parmenides’ notion of the fixed world, Heraclitus’ notion of the world in flux, Pythagoras’ abstract mathematics and Socrates’ notion of knowledge coming from reason.

Democritus was a Greek thinker. He postulated that things in the world could be divided continuously, but at some point they could not be divided anymore and we would arrive at non-divisibles, or a-toms. In the 20th Century scientists thought they had discovered these non-divisibles and called them atoms.

Challenges to Plato’s Theory

There are three main challenges to the theory of FORMs, the first two presented by Aristotle, Plato’s student:

Aristotle was Plato’s student. Where Plato was an idealist, Aristotle was an empiricist arguing that reality could be attained through the five senses.

1. Every FORM is a member of a class and so needs a FORM, leading to the Third Man Fallacy. If A, B and C each possess F-ness by partaking in F, they must (in their F-ness) resemble F. From the “symmetry of likeness” it follows that F must resemble A, B and C. This incurs the requirement of a further Form (F2) by virtue of which F resembles its instantiations—ad infinitum.

2. If there is a FORM of everything, then there are forms of negations and poor versions of things. In Metaphysics (Book XIII Part 4) Aristotle challenges Plato’s Theory of FORMs on the bases that the theory demands there to be FORMs of all sorts of unlikely things.

Of the ways in which it is proved that the Forms exist, none is convincing; for from some no inference necessarily follows, and from some arise Forms even of things of which they think there are no Forms. For according to the arguments from the sciences there will be Forms of all things of which there are sciences, and according to the argument of the ‘one over many’ there will be Forms even of negations, and according to the argument that thought has an object when the individual object has perished, there will be Forms of perishable things; for we have an image of these. (Republic)

3. In addition to this, there is a third challenge we can use: the theory of FORMs requires the belief in reincarnation which, while Pythagoras supported it, is far from certain, which undermines the theory. Plato was a dualist – meaning he believed in a mortal body and an eternal soul.The soul possessed innate ideas – and so the ideas of the FORMS are things we are born with. Thomas Aquinas develops and Christianises this and other Platonic ideas as Aquinas argues we are born with synderesis, a habit which orientates us naturally towards the good. Aquinas explains this synderesis as an ‘innate knowledge of first principles’ – what we describe in the Ethics course as the Primary Precepts.

D. Apply this to Sexual Ethics

At first a shudder runs through him, and again the old awe steals over him; then looking

upon the face of his beloved as of a god he reverences him, and if he were not afraid of being thought a downright madman, he would sacrifice to his beloved as to the image of a god; then while he gazes on him there is a sort of reaction, and the shudder passes into an unusual heat and perspiration. (Plato, 1937, p. 225)

The “ladder of love” occurs in Plato’s Symposium (c. 385-370 BC). It’s about a contest at a men’s banquet, involving impromptu philosophical speeches in praise of Eros, the Greek god of love and sexual desire. Socrates summarised the speeches of five of the guests and then recounted the teachings of a priestess, Diotima. The ladder is a metaphor for the ascent a lover might make from purely physical attraction to something beautiful, as a beautiful body, the lowest rung, to actual contemplation of the Form of Beauty itself.

Diotima maps out the stages in this ascent in terms of what sort of beautiful thing the lover desires and is drawn toward.

1. Sexual attraction to a particular beautiful body. This is the starting point, when love, which by definition is a desire for something we don’t have, is first aroused by the sight of individual beauty.

2. All beautiful bodies. According to standard Platonic doctrine, all beautiful bodies share something in common, something the lover eventually comes to recognize. When he does recognize this, he moves beyond a passion for any particular body.

3. Beautiful souls. Next, the lover comes to realize that spiritual and moral beauty matters much more than physical beauty. So he will now yearn for the sort of interaction with noble characters that will help him become a better person.

4. Beautiful laws and institutions. These are created by good people (beautiful souls) and are the conditions which foster moral beauty.

5. The beauty of knowledge. The lover turns his attention to all kinds of knowledge, but particularly, in the end to philosophical understanding. (Although the reason for this turn isn’t stated, it is presumably because philosophical wisdom is what underpins good laws and institutions.)

Beauty itself – that is, the Form of the Beautiful. This is described as “an everlasting loveliness which neither comes nor goes, which neither flowers nor fades.” It is the very essence of beauty, “subsisting of itself and by itself in an eternal oneness.” And every particular beautiful thing is beautiful because of its connection to this Form.

The lover who has ascended the ladder apprehends the Form of Beauty in a kind of vision or revelation, not through words or in the way that other sorts of more ordinary knowledge are known.

Diotima tells Socrates that if he ever reached the highest rung on the ladder and contemplated the Form of Beauty, he would never again be seduced by the physical attractions of beautiful youths. Nothing could make life more worth living than enjoying this sort of vision. Because the Form of Beauty is perfect, it will inspire perfect virtue in those who contemplate it.

This account of the ladder of love is the source for the familiar notion of Platonic (non-sexual) love.

The description of the ascent can be viewed as an account of sublimation, the process of transforming one sort of impulse into another, usually, one that is viewed as “higher” or more valuable. In this instance, the sexual desire for a beautiful body becomes sublimated into a desire for philosophical understanding and insight. (source: Emrys Westacott).

“Plato’s view of love can be helpful both in dispelling our confusion about love and in proposing some solutions to our suffering. To the Greeks, beauty was a function of harmony; it arose from a harmonious relationship between parts that could not cohere unless they were good for one another. From this Plato concludes that what is truly beautiful must be good and what is truly good must be beautiful.”. (Lydia Amir, Practical Philosophy November 2001)

So (paradoxically, and coming from a very different time and place) Plato would agree with situation ethicistJoseph Fletcher – love is all you need. In sexual ethics we need, Plato would argue, to understand what our desire is for. Even our sexual desire is actually for something greater – harmony, wholeness, beauty. In our sexual relations we are prisoners in a cave – chasing shadows which never satisfy. If we can escape the cave we will discover a higher purpose and find an explanation for our discontent. We can embrace the creative side of eros and escape the destructive. I leave Richard Kraut the last word from the Oxford Handbook on Plato:

We must not take Plato to suppose that we should treat other human beings, beautiful in body or soul or both, as mere stepping‐stones on the way to the vision of beauty itself. The best sort of lover is someone who is bursting with ideas about how to improve human life. Because we cannot fully understand or develop those ideas on our own, we need a conversational partner who will help us nurture those inchoate theories. That we need a partner in order to fulfil our need to give birth to a better world does not show that it is only our needs that matter to us. In the best kinds of erôs, self‐regard and dedication to others mutually reinforce each other; in the worst kinds, a lover destroys himself as he goes about destroying others. Richard Kraut

0 Comments