Handout – Liberation Theology of Gutierrez and Boff

October 29, 2018

Liberation Theology

Introduction – Individual Gospel versus the Social Gospel

A fault line has opened up between the individualistic Christianity of the West and the Social Gospel Christianity of countries, for example, in Latin America. These latter countries have been deeply influenced by what is called PRAXIS – meaning the context and experience of ordinary life. This life is marked by inequalities even more extreme than found in western economies, and by corruption and indifference to the plight of the poor.

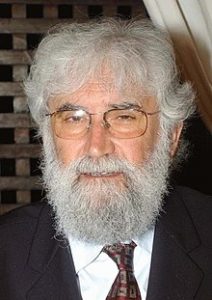

Leonardo Boff resigned his priesthood in 1992 in protest at his treatment by the Catholic Church.

Such countries have produced theologians like Leonardo Boff of Brazil, or Gustavo Guiterrez from Peru, who have spoken out and produced their own theology of liberation – and been punished for it. In 1985, for example, Leonardo Boff was summoned to the Vatican to explain his teachings: he resigned his priesthood in 1992.

In his 1984 book Church: Charism and Power, Boff wrote that the church’s hierarchical structure was not intended by Christ and that authority can spring from the community of the faithful. The Vatican’s doctrinal enforcement agency, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, called the book as “dangerous” and ordered Boff to stop teaching or writing for a year. Boff complained of being ” hounded by doctrinal authorities of the Vatican, who “became like an ever-tightening tourniquet rendering my work as a theologian, teacher, lecturer, adviser, and writer almost impossible.” Yet years later, in 2015, the founder of liberation theology, Gustavo Gutierrez, claimed that Pope Francis used him as a key source for the papal encyclical Laudate Si. Liberation Theology had finally entered the inner sanctum.

Arguably western Christianity has been captured by its own praxis (practical context) – the praxis of individualism, wealth-creation and perfectionism. So Pentecostalists pray that God would heal me, not heal the world and its injustices. US Christians have in places followed a prosperity gospel, meaning that God blesses believers with great wealth as a sign of divine good will. Congregations seem reluctant to give away more than 3% of their income – so that western congregations barely give enough to sustain their own minister in his or her job. Paradoxically, western Christianity is bedevilled with self-doubt and its people likely to be richer but less happy than those in Latin America. Christianity in the western churches is in decline: in Latin America it is booming.

Liberation and other Justice Movements

There are similarities between Liberation and feminist theologies, for example, the theology of Rosemary Radford Ruether, as illustrated by the table below.

| Leonardo Boff | Rosemary Ruether |

| Argues the experience of oppressed communities is the key to interpreting God’s will. | Argues that the experience of women as the oppressed is the key to understanding which parts of the Bible are authoritative. |

| Sees the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah’s call to liberate the oppressed as key passages of the Bible. | Sees the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah’s call to liberate the oppressed as key passages of the Bible. |

| Argues that realised eschatology, where the kingdom of God is brought into the present, has to be practised, with equality of rich and poor. | Argues that realised eschatology ,where the kingdom of God is brought into the present has to be practised, with equality of male and female. |

| Sees history as instrumental to understanding how the gospel has been distorted and used to reinforce social class. Christianity is involved in history – both the symbolical and diabolical – in light and shadows. | Sees history as instrumental to understanding how the gospel has been distorted and used to reinforce gender division. History has to be reclaimed – the story of women and the lost history of Christianity in its early prophetic forms rediscovered. |

| Sees sin not in individual terms, but in structural terms and in terms of the misuse of power to justify elites and a power to oppress the masses. | Sees sin not in individual terms, but in structural terms and in terms of the misuse of power to keep women in a position of servility. |

A Preferential Option for the Poor

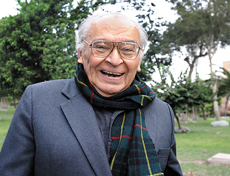

Gustavo Gutierrez (b.1983) defines the movement he founded thus:

‘Liberation theology is a theological reflection… born of shared efforts to abolish the current unjust situation and to build a different society, freer and more human.’

He invented the phrase ‘a preferential option for the poor’ to express the essential core of liberation theology.

Gutierrez introduced the phrase ‘a preferential option for the poor’ to explain a complete shift in the church’s focus.

As with the feminist writer Rosemary Ruether, he takes as one of his key biblical texts the Exodus story where Moses leads the children of Israel away from slavery in Egypt towards a new land ‘flowing with milk and honey’ and judgement is visited on Pharaoh’s armies as the waters of the Red Sea roll over them. “The God of Exodus is the God of history and of political liberation more than he is the God of nature”, proclaims Gutierrez.

Focus for a moment on the picture below. In the Brazilian city of Sao Paolo a poverty stricken shanty town exists alongside a rich apartment block complete with two swimming pools. The name for such shanty towns is the favela. This vivid image expresses the starting point of liberation theology – the praxis or practical situation which expresses a call to action. Indeed Gutierrez defines theology as ‘a critical reflection on praxis’, the social context seen through the lens of Scripture.

In Sao Paolo, Brazil, slums and rich apartments crowd together in a way unseen in Europe.

In this new hermeneutic (interpretation) of Scripture Gutierrez employs the Hegelian and Marxist idea of dialectic to explain how theology moves through eras and stages of development, of which the latest and most radical is liberation theology. It is liberation theology which is the true heir of the words and example of Jesus Christ who came to preach ‘good news to the poor’ and ‘let the oppressed go free’ (Luke 4:18) so heralding a new era of time – the epoch of the transformation called the Kingdom of God in this world, now.

It is the new hermeneutic that comes in for criticism by the Catholic Church in 1984. Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict,identifies a number of criticisms of Liberation Theology which we summarise in the evaluation at the end of this handout. By viewing the essential lens by which we interpret scripture as a bias towards the poor, and by seeing the poor as those in physical poverty, the Liberation Theologian reduces and distorts the idea of salvation for all to something reserved for a particular social class. Ratzinger accuses the Liberationists such as Gutierrez of reductionism, reducing the idea of salvation and the Kingdom of God to something less than it is. He writes:

“The new ‘hermeneutic’ inherent in the “theologies of liberation” leads to an essentially ‘political’ re-reading of the Scriptures. Thus, a major importance is given to the Exodus event inasmuch as it is a liberation from political servitude. Likewise, a political reading of the “Magnificat” is proposed. The mistake here is not in bringing attention to a political dimension of the readings of Scripture, but in making of this one dimension the principal or exclusive component. This leads to a reductionist reading of the Bible.” (1984 X 4,5)

Gutierrez, in contrast, sees history as

“The undisputed locus of theology… God is seen at work in all events of liberation and revolution. He speaks not only through Scripture but also through the political upheavals of our day. In fact, all of history is conceived of as sacred history, since all of history reveals even as it also hides the presence of God, who is understood to be in essence “the power of liberating love.” (A Theology of Liberation)

James Cone, a Black liberation theologian, is even more insistent that, the locus of theology must be in history. Cone writes:

“The proper eschatological perspective must be grounded in the historical present, thereby forcing the oppressed community to say NO to unjust treatment because their present humiliation is inconsistent with their promised future. No eschatological perspective is sufficient which does not challenge the present order. If contemplation about the future distorts the present reality of injustice and reconciles the oppressed to unjust treatment committed against them, then it is unchristian and thus has nothing whatsoever to do with him who came to liberate us. It is this that renders white talk about heaven and life after death fruitless for black people. . What good are golden crowns, slippers, white robes or even eternal life, if it means that we have to turn our backs on the pain and suffering of our own children?” (The Black Messiah)

The expression used for this is ‘realised eschatology’ – meaning that hope is not something that exists in a distant further beyond the grave but is realised in transformations in society now. White missionaries have always encouraged blacks to forget about present injustice and look forward to heavenly justice. But Black Theology says an emphatic ‘no’ to this and , insists that we either put new meaning into Christian hope by relating it to our liberation today. (Cone, 1970:241-2).

So in Latin America, liberation is forged in base communities of the poor living, acting, studying together, and creating a new order of being.

Marxism or Socialism?

When Gutierrez returned from studying in France in 1961 he found Peru a country of huge economic inequality, where 5% of people owned 45% of the land. Rural Indian populations were especially destitute. Gutierrez had studied the French revolution of 1789 but saw its limitations as a product of the Enlightenment and the links with radical atheism. Latin America required an entirely different approach which drew on the writings if Hegel and Marx.

Gutierrez seeks to bring Marx and Hegel together. Hegel was criticised by Marx for adopting a philosophy of “abstraction,” with consciousness as the key. Instead Marx sought to create a scientific understanding of history based on economics. There are three concepts particularly important in this adaptation of Marx: alienation, false consciousness and praxis. Let’s treat each in turn.

Alienation

In the development of his theological system Gutierrez reconciles Hegel and Marx, thereby claiming to create a new step in the dialectical development of human thought. For Hegel, dialectic is a process of becoming through negation, or othering in the form of an opposite, and then reconciling that other in a unity with the original.

For example, Hegel speaks of the master-slave relation. The master can only be ‘master’ in the sense of having a relation to a slave and vice versa. They are locked together in mutual relationship. They exist in a dialectic of opposites.

False consciousness

Gustavo Gutierrez argues that as well as liberating people from unfair laws, economic oppression and a class system, people also need to be liberated from ideas that restrict their ability to flourish as human beings.

Liberative hermeneutics plays an important role in consciousness-raising. Stories like the Exodus and Jesus’ message to the poor are used to judge poverty as a direct result of sin. This message contrasts with what the Church had sometimes taught – that wealth is a reward from God and that people should accept their God-given lot in life. Notice the judgment on the church itself, which liberation theologians see as part of the structure of oppression itself – as bound up in a corrupt system of power and control.

Praxis

For the liberation theologians theology begins and ends in the life of a Christian community. Ideas and life are interrelated in the community. As a local church is not detached from its place or culture, so theology is not composed by individuals in an ivory tower. Nor is it simply given from above, in an infallible source-book. Instead, Christian thinkers are part of a Christian community. They reflect on God’s self-disclosure through the hopes and struggles of that group, and the wider society beyond. In the same may, the final test of a theology is in the transformed lives of its community. The hope of a reconstituted society is what lies behind the fondness of liberation theologians for the word praxis, which means ‘practical action within a local context’.

Jon Sobrino calls this praxis-action-reflection approach to Scripture the ‘hermeneutic circle’.

Hermeneutics means ‘interpretation’ and readily acknowledges (as evangelical Christianity, for example, rarely does) that interpretation of the Bible is always done through the eyes, ideas and values of a culture. Here feminist theologians such as Rosemary Ruether can also be seen as liberationists as they adopt a hermeneutic of suspicion of the ways in which patriarchal values have corrupted the reading of the Bible. A feminist hermeneutic simply rejects anything which seems to suggest in the Bible the inequality, subjugation or oppression of women (for example, the purity code written in Leviticus 18 which bans menstruating women from the Temple courts).

Instead of a hermeneutic which removes parts of the Bible as unjustified, as in feminism, Gutierrez argues for a rediscovery of the radical, political Christ who overturns the tables of money-changers in the Temple and embraces the bleeding woman who quietly pollutes him by her touch as ‘my daughter’ (see Mark 5). We discover and embrace this Christ and then follow his way. Gutierrez’s spirituality is the spirituality of direct action – we find God in our actions and not through passive contemplation of icons or the Bible.

The starting point is the situation or context of the poor who live alongside the rich in a permanent state of economic servitude. This moves to the next stage of reflection whereby the believing Christian meditates on what God might be saying in and through the context of poverty. The conclusions are radical: God sides with the poor and the poor are what John Paul II called in 1979 “God’s favourites”.

Within this action-reflection circle we find liberation has three meanings according to Gutierrez:

1. Political – it is “at odds with wealthy nations and oppressive classes”.

2. Psychological – it calls human beings to take responsibility for their destiny – to

rise up, to refuse to accept injustice, to fight (not literally as Guitterez does not adopt the direct violence for which Torres died).

3. Theological – “Christ the Saviour liberates from sin, which is the ultimate root of all injustice and oppression”. Guitterez

It is little wonder that American politicians sought to investigate this dangerous, theology of revolution which they thought of as a Marxist theology of revolution. It is far cry from the individualistic, passive and other-worldly expressions of Christianity found in many western churches and it also drew criticism from Cardinal Ratzinger’s paper in 1984 which stated that:

“Let us recall the fact that atheism and the denial of the human person, his liberty and rights, are at the core of the Marxist theory. This theory, then, contains errors which directly threaten the truths of the faith regarding the eternal destiny of individual persons.” (1984 VII.9)

Liberation theologians such as Gutierrez insist that Marx is only an inspiration and his analysis of class a helpful stepping stone. In A Theology of Liberation, Gustavo Gutierrez calls for “a radical break from the status quo” here identified as the “private property system” claiming that such a move would create possibilities for a new society, “a socialist society,” he continues, “or at least allow that such a society might be possible.” Socialism stresses social justice and equality here the two movements intertwine. in seeking to discern the social, political, and economic arrangements that allow for God’s reign to flourish in our midst, Gutierrez concedes that socialism is the best option.

Moreover, according to Gutierrez it matters not what are the moral and spiritual conditions of the poor, whether they are thieves, prostitutes or murderers. He says:

“God, as Christ shows us, loves the poor for their concrete, real conditions of poverty whatever may be their moral or spiritual disposition”.

There are implications here for a very inclusive model of salvation which places liberation theology at odds with evangelical Christianity’s emphasis on personal repentance and faith.

The Kingdom of God

The idea of the Kingdom of God gains radical new meaning with the advent of Liberation Theology, and with it, the key concepts of sin and salvation take on a different meaning.

For Gutierrez, sin is a structural idea born of injustice. He writes: ‘Poverty is an evil, a scandalous condition, which in our times has taken on enormous proportions.’ (T of L page 168)

He defines poverty here as a real, material lack of wealth.

‘It is a concrete material poverty, and no poverty of spirit, or any other of its form. This form of poverty means death, lack of food and housing, the inability to afford health and education, the exploitation of workers, permanent unemployment, the lack of respect for one’s dignity’ (Theology of Liberation, page 162)

So, a bit like Karl Rahners’ anonymous Christian, we are saved even if we’re not aware of it. ‘Individuals are saved if open to God and to their fellow man, even if they are not aware of it. This applies to both the Christians and the non-Christians -to all men.’ (T of L page 84)

Yet salvation includes especially the poor and oppressed, because in this process, the poor and the oppressed become a new creature. Human living conditions, owning what is necessary, overcoming all social evils, the advancement of knowledge and culture, in other words, completely filling and regeneration of men.

Reading Gutierrez’s book A Theology of Liberation gives the strong impression he believes that the realisation of salvation is possible and achievable now. He is aware that it sounds utopian and therefore has a different definition of the term. ‘Utopia’ is related to historical reality, confirmed in practice and rational by nature. So, according to this view, utopia does not describe something impossible: it is achievable today by direct action.

He moderates this view later to point out that not everything can be realised today.

“I think that it is important to avoid Messianism. We Christians are among those people who can do a lot in this world. This is true. At the same time, we must keep aware of the relationship between the fullness of the Kingdom of God, which is fulfilled beyond history, and the fact that we here and now are beginning to construct history. This is not a simple task as they are two things that belong together, even if people try to separate them. When somebody talks a lot about justice, people often say, ‘Do you think that it is possible to build a paradise on earth?’ As a Christian, I do not believe that. At the same time, I do not believe that people must live in the hell they are living in today.” Guiterrez, ‘Faith and Politics in the Popular Movement Today,’ p. 180

Gutierrez confirmed during the fifteenth anniversary of his book that ‘he himself no longer holds to everything he had written in the original volume,’ but this change of mind he compared with love in marriage. It remains alive but is deepening and changing its form of expression.

Leonardo Boff and the Three Mediations

The Medellin conference report of 1968 begins with the sonorous declaration:

“There are many studies of the Latin American people. All of these studies describe the misery that besets large masses of human beings in all of our countries. That misery, as a collective fact, expresses itself as injustice which cries to the heavens.” (Medellin, 1968)

In his writings Leonardo Boff describes how three mediations, or ways of seeing, are required to produce a liberated way of seeing, and so provide a framework for acting upon oppression and poverty.

1. The Socio-analytic Mediation

Leonardo Boff uses Marx’s ideas as a tool for the socio-analytic mediation. Marx provided a way of understanding poverty in terms of exploitation. For liberation theologians, whose aim is to try to end poverty, understanding the cause is important (to solve a problem you must first understand what causes it). Echoing the writings of Guttierez, Boff declares:

“God is in the poor who cry out. And God is the one who listens to the cry and liberates, so that the poor no longer need to cry out.” (Leonardo Boff)

Liberation theologians do not generally go as far as to argue for a wholesale rejection of capitalism but they do think that Marx provides a very useful critique of the excesses of capitalism.

In Latin America, the tradition of latifundia and hacienda (estates) meant that much of the land was in the hands of wealthy land owners who were in a position to exploit their work force.The Catholic Church and religious orders , especially the Jesuits, acquired vast hacienda holdings or preferentially loaned money to estate owners. As the hacienda owners’ mortgage holders, the Church’s interests were thereby connected with the landholding class. In the history of Mexico and other Latin American countries, the masses developed some hostility to the church; at times of gaining independence or during certain political movements, the people confiscated the church haciendas or restricted them.Consequently, Marx seemed to provide an accurate explanation of the problems in Latin America and the struggle for economic rights and greater equality.

2. Hermeneutic Mediation

The second mediation Boff calls the judging mediation (or hermeneutic mediation, where hermeneutics means ‘interpretation’). The judging mediation occurs between the seeing mediation and the acting mediation and it is important to understand how the mediations work together. Boff calls this a ‘new optic’ – or new way of looking at Scripture through the context of social inequalities:

To think and to act in terms of liberation.. implies a hermeneutical turnaround and the enthronement of a new state of consciousness.. . Now we live under the dominion of this new age that permits a different reading of the texts and historical contexts of both past and present within the horizon of liberation or oppression. (Boff, Salvation and Liberation page121)

The seeing mediation is used to understand and see accurately and clearly the mechanics of society and the causes of poverty. Boff argues that Marx is used in this mediation to help understand the political and economic contributions to poverty. However, the standard of moral judgement is the Bible and particularly the call for justice in such books as Isaiah and Jeremiah, or the call to renounce slavery in the book of Exodus. As the Medellin conference declared: ‘The Christian need for justice is a demand arising from biblical teaching.’

3. The Acting Mediation

The acting mediation comes last and follows on from seeing/understanding and judging social circumstances and class relations against the call for justice in the Bible. The action should be motivated by Biblical teachings and in this way the hermeneutic mediation (the right interpretation of social circumstances in the light of Bible teaching) contributes to orthopraxis, meaning ‘right action’. The Medellin conference declared:

“Love is ‘the dynamism which ought to motivate Christians to realise justice in the world. We believe that the Latin American Episcopate cannot avoid assuming very concrete responsibilities because to create a just social order is an eminently Christian task.’” (Medellin, 1968)

A Critique of Liberation Theology: Libertatis Nuntius 1984

It is worth reading the two extracts on this site- one from 1984, written by Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict) criticising the liberation theologians, and one from 2015, Laudate Si, from Pope Francis, himself a Latin American. Laudate Si for example, quotes the Latin American bishops with approval in calling for a right to own land:

The rich and the poor have equal dignity, for “the Lord is the maker of them all” (Prov 22:2). This has practical consequences, such as those pointed out by the bishops of Paraguay: “Every campesino has a natural right to possess a reasonable allotment of land where he can establish his home, work for subsistence of his family and a secure life. This right must be guaranteed so that its exercise is not illusory but real. That means that apart from the ownership of property, rural people must have access to means of technical education, credit, insurance, and markets” (Laudate Si 2015 para 94).

A summary of Ratzinger’s four principal criticisms in Libertatis Nuntius is given here:

A recent papal encyclical Laudate Si takes a much more sympathetic line on liberation theology and the search for justice.

1. Liberation theologians make too much use of Marx. This is problematic because Marxist thought all relates together so even if ideas are intended to be used in isolation they still relate to the whole thing. Marxist ideas like class-struggle and atheism are at odds with Christianity, however accepting Marxist analysis of the problems makes entering into class-struggle a duty.

2. Liberation theologians read Biblical stories in such a way that the political/social message is the only one of interest to them. It is not a mistake to see a political message, but it is a mistake to see it as the only message.

3. Liberation theologians prioritise dealing with social and structural sin without recognising that personal sin is the real problem. Liberation theologians need to recognise that evil structures come from evil people, not the other way round.

4. Liberation theology confusing human effort and human social progress with salvation and the Kingdom of God. They do not recognise that real salvation comes from God and only from God.

0 Comments