Handout: Knowledge of God

September 28, 2016

Knowledge of God

Knowledge of God presents a particular difficulty for us because the knowledge we might be claiming is not like other forms of knowledge. It is also under attack by writers like Richard Dawkins in the modern era who claims that:

Faith is the great cop-out, the great excuse to evade the need to think and evaluate evidence. Faith is belief in spite of, even perhaps because of, the lack of evidence. Richard Dawkins, 1992

Consider the following possible forms of knowledge:

- Factual – can be tested by some (empirical) process or evidence gathering (beloved of Dawkins). Example, there is a

Richard Dawkins attacks Christianity for its faith position, but fails to see his own faith position, according to Professor Alister McGrath.

chair in this room, so I go and touch it if I need to check.

- Abstract – sometimes called a priori knowledge because it’s ‘before experience’. These are categories of knowledge created by the human mind. Consider the category of ‘number’. 3 + 3 = 6 and not 9 just because that’s how the numbers work. The symbol 3 represents something by definition and the relation between 3 and 6 is logically set up by the human invention of number.

- Personal – “I know my son Charlie”. I know him because since birth he and I have had a relationship of father and son. This means I know not just what he looks like. I know something of what makes him tick and what are his strengths and weaknesses. I know him. I A body, a character and a person.

- Functional or skill-based knowledge – “I know how to sail’. I have sailed all my life, and it’s now a second instinct for me. I no longer think about it when I’m in a sailing boat. I know it.

- Metaphysical – is there a category of knowledge that is ‘beyond science’ in that it is not subject to empirical testing and proof in that sense? Of course, there is. Consider perception. What you ‘see’ when you look at something doesn’t exist as a ‘thing’ in your brain – like a TV screen. It only ‘exist’ in that sense as a set of electrical impulses. Actually the light waves pass into your brain as an upside-down image and then (cleverly) get turned right way up and ordered by our minds. Much as philosophers might try to explain perception, it remains meta-physical (as does memory, reason and belief to name three more mental ideas).

When we talk of knowledge of God this kind of knowledge exists on the personal/metaphysical axis. It is beyond scientific proof. It is beyond a priori proof (despite the best efforts of Anselm’s a priori ontological argument). It is not a skill – but it is an idea which people claim is ‘like a personal relationship’. And it is definitely metaphysical, with other ideas and experiences like beauty, goodness, belief, memory and perception.

Yet we seem as human beings to talk about it (religious language) and experience God (religious experience).

Beauty and Goodness

John Calvin begins his Institutes by asking the question “how can I know anything about God?’ Calvin argues that knowledge in the fullest sense is only possible through the Bible – because here God has chosen to reveal what he is like. He does this in both testaments, old and new.

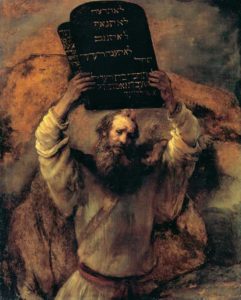

God reveals himself in two ways, according to Calvin: the Bible and nature. Here Moses smashes the ten commandments in anger at the idolatry of Israel, just after God reveals himself to Moses on Mt Sinai.

Consider the extraordinary revelation of God to Moses on Mount Sinai. We read in Exodus 34 that God passes in front of Moses and then declares his name – Yahweh which means ‘the great I am’ or the eternally present one.

God then reveals his character. Can God have a character given he is invisible?

According to the Bible the answer is a resounding ‘yes’. God’s character is revealed as possessing a number of great moral qualities which then become the bedrock of biblical ethics. Despite what divine command theory suggests or some fundamentalist Christians preach, it is the character of God which is the source of the divine law.

Then the LORD came down in the cloud and stood there with him and proclaimed his name, the LORD. 6 And he passed in front of Moses, proclaiming, “The LORD, the LORD, the compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness, 7 maintaining love to thousands,and forgiving wickedness, rebellion and sin. Yet he does not leave the guilty unpunished; he punishes the children and their children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation.” (Exodus 34: 5-6)

It seems an obvious point but it’s one people miss: the revelation of God’s character comes before the covenant and the law. So what are these characteristics of God?

• Compassion. God feels with his people.

• Graciousness and love. The Hebrew word is hesed and it occurs 127 times in the Old Testament to express a primary quality of God’s relationship to human beings and also the ideal relationship of humans to each other. It means steadfast love, loyalty, commitment love and loving-kindness. It is the Hebrew origin of the Greek word agape.

• Faithfulness. This Hebrew word emeth includes the idea of truth – faithfulness to self and also integrity. It also means faithfulness to those we have committed ourselves to be faithful to – God always keeps his promises. God’s covenant is unbreakable.

• Justice. God punishes the guilty with a just retribution. Evil will have consequences.

But this and other revelations are only found by reading Scripture and in the New testament we find al of them embodied in Jesus Christ, full of ‘grace and truth’ (John 1) or ‘steadfast love and faithfulness’ – using the Hebrew words (hesed and emeth) introduced above.

Natural Knowledge is also Possible

Calvin also argues that natural knowledge of God takes us some way towards faith. We should not discount it. It is the natural knowledge we can get from looking around ourselves at the world and inside ourselves at our conscience that leads us towards the true knowledge found in the Bible.

There is within the human mind, given by natural instinct, a divine sense (sensus divinitatis). This is beyond any argument. We can’t use ignorance as an excuse. God can freshen up this awareness and heighten it at any time. People then recognise the creative force behind life but are self-condemned when they don’t worship him as such. Ignorance in its fullest sense can only be found among the uncivilised and backward peoples – but in fact we cannot find any such peoples – even tribal cultures recognise the divine. Every civilisation has had a sense of the divine written into their hearts. (Institutes)

John Calvin (1509-1564) argues we all have a sensus divinitatis – a shared sense of the divine which allows us to ‘see’ God in the natural world.

Calvin is therefore arguing that every human being shares in a sense of the metaphysical origins of life which are present in the beauty and design of the Universe – are revealed in every science, in biology physics and chemistry. We tap into the awesomeness of this design every time we make a new discovery, gaze at the stars or examine cells in a microscope. Some of it remains a mystery but the origin of it all though beyond comprehension (God is so great) is nonetheless not ultimately a mystery. We can know God.

Notice that this is a universal shared tendency of human beings. God is present in and reflected in the created order. So Calvin sees creation as a mirror or theatre that reflects the character of God as love and faithfulness. Behind the universe is a mind who creates and then orders and sustains. By looking at the beauty of creation we can infer his characteristics of love, faithfulness and wisdom. And notice the beauty is a beauty of design, of form, as well as of colour, of patterns in the sky. This to Calvin, makes the natural order a ‘mirror’ – ‘this skilful ordering is for us a sort of mirror in which we can contemplate God who is invisible’.

The Deficiency of Natural Theology

Calvin also argues that natural theology only takes us so far. Indeed, because human beings are infected with sin in every faculty of our being, the mirror image we see is hazy and distorted. It’s as though we have a very heavy pair of sunglasses on which are tinted red. The redness (sin by analogy) affects everything we see – even the natural traces of God in the world.

Not only is God by definition immortal, invisible and all powerful (by contrast we are mortal, visible and of limited power) but sin makes the distance between us even larger. Alistair McGrath puts it like this:

Calvin argues that the epistemic distance (meaning a knowledge gap) between God and humanity, already of enormous magnitude, is increased still on account of human sin. Our natural knowledge of God is imperfect and confused, even to the point of contradiction on occasion. A natural knowledge of God serves to deprive humanity of any excuse for ignoring the divine will; nevertheless it is inadequate as the basis for a fully fledged portrayal of the nature, character and purposes of God. (McGrath, 2011:161)

Design Arguments and Dialectical Theism

The argument from design is also called the teleological argument and one of its classical exponents was William Paley (1743-1805). Paley’s argumets impressed,a nd indeed inpired Charles Darwin who wrote:

The logic of this book and as I may add of his Natural Theology gave me as much delight as did Euclid. The careful study of these works, without attempting to learn any part by rote, was the only part of the Academical Course which, as I then felt and as I still believe, was of the least use to me in the education of my mind. I did not at that time trouble myself about Paley’s premises; and taking these on trust I was charmed and convinced of the long line of argumentation. Charles Darwin

William Paley (1743-1805) much impressed the young Darwin, even if Darwin came to very different conclusions about the origin of species.

Paley was impressed by Newton’s ‘celestial mechanics’ – the idea that the universe operates like a gigantic mechanism behind which there are laws of motion, gravity, mass and so on. Newton, with echoes of Paley’s argument, believed that the universe was like a massive clock built by a creating god and set into motion.

Newton’s mechanistic view of the universe was based on the concept of inertia. Every object remains at rest until moved by another object and every object in motion stays in motion until stopped by another object. And underlying it all were laws of gravity, and mathematics.

Paley takes up this mechanistic idea in a famous analogy. He imagines going for a walk and stumbling on a watch. He meditates on a difference between the watch and a stone.

“When we come to inspect the watch we perceive – what we could not discover in the stone – that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose – that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and motion so regulated to point out the hour of the day. Once observed and understood, the inference we think inevitable, that the watch must have a maker”. Paley

What is Paley really arguing here? In contrast to Dawkins who argues in The Blind Watchmaker that ‘there is no purpose’, merely random reactions in a battle to survive, Paley sees order, purpose and design everywhere. Things are arranged so as to produce something else – a purposive element to creation. The sun emits heat (my example), heat makes plants grow, they photosynthesise and recycle carbon into oxygen, the oxygen stays stable as a proportion of the atmosphere of the earth and so life is sustained – that is the point.

He concludes that:

“Every indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design which existed in a watch, exists in the works of nature”. William Paley

David Hume’s Critique of Design

David Hume (1711-1776) wrote:

“That a stone will fall, that fire will burn, that the earth has solidity, we have observed a thousand and a thousand times; and when any new instance of this nature is presented, we draw without hesitation the accustomed inference. But how this argument can have place where the objects, as in the present case, are single, individual, without parallel or specific resemblance, may be difficult to explain. That all inferences concerning fact are founded on the supposition that similar causes prove similar effects, and similar effects, similar causes, I shall not at present much dispute with you. But observe, I entreat you, with what extreme caution all just reasoners proceed in the transferring of experiments to similar cases. Unless the cases be exactly similar, they repose no perfect confidence in applying their past observation to any particular phenomenon. If we see a house we conclude, with the greatest certainty, that it had an architect or builder because this is precisely the species of effect which we have experienced to proceed from that species of cause. But surely you will not affirm that the universe bears such a resemblance to a house that we can with the same certainty infer a similar cause, or that the analogy here is entire and perfect. The dissimilitude is so striking that the utmost you can here pretend to is a guess ” David Hume

David Hume (1711-1776) was a contemporary of Paley who pointed out major flaws in his argument from design.

Hume is pointing out that we make references about what brought something about based on past experience of similar things. Houses tend to have architects. But with the universe there is no such regularity to draw upon – we can only experience our little bit of one universe. We can as easily infer a big bang as a designer. Moreover we are transferring one idea of causation – houses have architects – to another – the Universe has an architect. We are jumping categories here, from ‘house’ to ‘universe’ or in Paley’s case, ‘watch’ to ‘universe’. That’s the problem with analogies – the dissimilitude (lack of similarity) is glaring.

Using McGrath’s summary of Hume’s rejection, we can say there are three difficulties with Paley’s argument (2011:187).

1. The direct extrapolation from the observation of design to a good God who designed it is not possible. All we can infer is that there might just be a designer (but not one with any particular qualities).

2. Who designed the designer? There would seem to be an infinite regression. Aquinas argues that it is self-evident that there is no regression. But Hume rejects Aquinas’ argument as he thinks this sort of reasoning begs the question – who deigns the designer? Where did the designer come from? Just saying ‘he doesn’t come from anywhere’ isn’t very convincing – the designer becomes an assumption, not an argument.

3. The analogy with a machine like a watch is not the only analogy. Why not say the universe is like a plant – always growing, always developing? Would this not be truer to the organic nature of the ever –expanding and changing universe?

Moreover, Hume concludes (a point McGrath doesn’t mention) – just look at the faults in the design. Viruses, tsunamis, earthquakes, starvation, meteorites – we might as well infer a rather bad god as a good one, a baby god who started making something and got rather bored.

“The world, for aught he knows, is very faulty and imperfect, compared to a superior standard; and was only the first rude essay of some infant deity who afterwards abandoned it, ashamed of his lame performance: It is the work only of some dependent, inferior deity, and is the object of derision to his superiors: It is the production of old age and dotage in some superannuated deity; and ever since his death has run on at adventures, from the first impulse and active force which it received from him”. David Hume

Alister McGrath – New Natural Theology

Alister McGrath argues that the old approach of natural theologians which emerged during the Enlightenment (from the sixteenth century onwards) was misplaced because it tried to prove the existence of God a posteriori (ie from experience of the natural world).

But this is impossible because, as Luther recognised and Hume made clear, the natural world is ambiguous – the source of good and evil, as Luther put it, simul bona et mala: it is marked by “beauty and ugliness, joy and pain, good and evil” . McGrath suggests that nature should thus be interpreted within the context of the story of salvation, so that we perceive the created world to be “decayed and ambivalent.” He writes:

“The created world is morally and aesthetically variegated entity whose goodness and beauty are often opaque and hidden, yet is nevertheless irradiated with the hope of transformation” (A Fine-Tuned Universe, 2009:82).

Alister McGrath takes inspiration from CS Lewis and from Augustine in arguing for a new direction for natural theology. Photo: Matthias Asgeirsson

In an earlier book, The Open Secret (2008), McGrath explains that a new “natural theology” can provide an “explanatory unification” which makes sense of various mysterious observable phenomena. Nature becomes a ‘bearer of transcendence”. McGrath points out there is no mere uninterpreted nature, but only different “readings” of nature. So the role of theology is to present a lens, like taking a pair of binoculars and examining raw data through the magnifcation of a belief in a trinitarian God (Father, Son and Holy Spirt).

We all have these faith systems – even Richard Dawkins posits elements of his theory which cannot be proven empirically (such as the idea of a selfish gene, or the idea of inherited cultural ‘memes’). Just as Dawkins has a framework of evolutionary faith, so does the Christian believer. According to McGrath, we can take elements of Augustine’s trinitarian theology and rework a new natural theology that makes sense of the diversity and mystery of human experience and restores a creator-redeemer God as the one behind and within all things. This is not a proof – more of a working supposition which arguably makes more sense of reality than any other,

This whole new approach to natural theology is best summed up in C. S. Lewis’s famous remark:

“I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.”

John MacQuarrie Dialectical Theism

Macquarrie believes the classical arguments for God over-emphasise certain attributes. These attributes seem to reflect a certain stage of history – male-dominated, authoritarian and ‘top-down” in its style of government (there’s a synoptic link here to the Christian Thought section on feminism). For instance, it has over-emphasised divine transcendence, resulting in a “monarchical” picture of a God who is removed and aloof from creation, devoid of softening or feminine features.

“The intellect demands a more dialectical concept of God, while the religious consciousness, too, seeks a God with whom more affinity can be felt, without diminution of his otherness”. John Macquarrie

Macquarrie describes a series of six “dialectical contrasts”, each side of which he thinks we need to attribute to God in order to have a more adequate concept of deity:

– Being and nothing: God is being, or as Macquarrie prefers to say, the power of “letting-be.” At the same time, God doesn’t exist in space-time and so doesn’t ‘exist’ in that sense. God is the creative being or source not a ‘thing’ or ‘being’ like us.

– The one and the many: God is beyond numbering and is the ultimate unity that grounds the great range and variety of physical things. But there are also reasons for thinking that there is a kind of differentiation within the being of God: a divine “abyss,” and intelligible self-manifestation, and a drive toward unity or communion (with echoes here of the Trinity).

– Knowability and incomprehensibility: Because God expresses himself in creation, God is knowable, “intuited in the world as a presence or as its unity.” But this knowledge is indirect, mediated by symbols, and the inexhaustible being of God transcends what we can know about him.

–Transcendence and immanence: God is independent of the world in the sense that the world depends on God for its existence. But God is also deeply involved in the world, intimately present to the processes that make it up. Images of “making” and “emanation” provide complementary ways of picturing the act of divine creation.

– Impassibility and passibility: Because God transcends the world, the suffering in the world cannot overwhelm or destroy him–or ultimately defeat God’s purposes. But God experiences what happens in the world and it affects him–the world matters to God. Its history makes a real contribution to the divine life.

– Eternity and temporality: God transcends the succession of past, present, and future and “remains constant and faithful, neither his power nor his love is diminished by the passage of time” (p. 182). But God is also involved in the movement of time, “engaged in the struggle,” “an active participant.” “God is himself in the events of history and is concerned about their outcome” (p. 182).

It is paradoxical to see God in terms of opposites which require both to be believed. Macquarrie thinks these contradictory attributes qualify each other. So we might say that “classical theism”–the view of God as utterly transcendent, impassible, omnipotent, provides the “thesis.”

But these properties are qualified by their antitheses, ultimately resulting in a “synthesis” that is still recognisable a form of theism. So, for example, Macquarrie says that God is impassible in certain respects – his essence, his character, his existence are eternal and unchangeable. But God’s experience of the world is genuinely affected by what happens “here below.” So he’s not simply saying that God is fully impassible and fully “passible,” but that God’s impassibility holds in certain respects and not others.

To conclude; Macquarrie offers reasons for thinking that the main alternative views of knowledge of God – classical theism, atheism, and full-blown pantheism – are unsatisfactory. His answer, somewhat paradoxically is to argue that God’s nature contains dialectical opposites which are held in tension.

The Limits of Natural Theology

Recall that Calvin argues that there are two ways of knowing God, natural (observed in the world) and revealed (read in the Bible), but that sin has clouded our sight like we were wearing heavily tinted spectacles. There is also a third internal mechanism – conscience. Here Calvin partly agrees with Aquinas who argues that the first principle of morality is synderesis – Aquinas’ word for an innate sense of right and wrong and the desire to follow the good. It’s worth dwelling on what Calvin actually writes for a moment:

Through the mind and understanding we grasp a knowledge of things, and from this are said “to know,” this is the source of the word “knowledge”. But also, they have a sense of divine judgment, as a witness joined to them, which does not allow them to hide their sins from being accused before the Judge’s tribunal, and this sense is called “conscience.” For conscience is a certain channel between God and man, because it does not allow man to hide what he knows, but pursues him to the point of convicting him…Therefore this awareness which summons us before God’s judgment is a sort of guardian appointed for us to note and spy out all our secrets, that nothing may be buried in darkness.” Institutes iii.iii

For Calvin conscience is a universal, shared faculty of the soul which pushes us towards God and is answerable to God on the day of judgement – whether we recognise god or not as its origin. Unlike our modern view, which, influenced by Freud, sees conscience as subjective and often irrational guilt feelings, to Calvin conscience is the God-give channel which connects us to an objective unseen reality. We feel guilty (subjective) because God is using conscience to draw us closer to ultimate reality – the unseen presence of the Creator and sustainer of the universe.

The Effect of The Fall

Calvin asks us to consider what would have happened if Adam had never grabbed that apple and eaten it. If Adam had remained whole and untainted by sin (si integer stetisset Adam), how might things have been?

Calvin’s answer is that we would have remained in a ‘primal and simple knowledge of God’. The final aspect of knowledge of God is relational. We need to accept the divine forgiveness and reconciliation offered to us through Jesus Christ and then re-enter that relationship destroyed by sin when Adam fell in the Garden of Eden. This, as Alister McGrath points out, will cause us to ‘see all things new’.

The raw data of experience get reinterpreted in the light of faith, and ‘by it we see everything else’ (CS Lewis).

Peter Baron April 2019

Some quotes to discuss

There is within the human mind an awareness of the divine This is beyond argument. John Calvin

Nearly all the wisdom we possess consists of two parts, knowledge of God and of ourselves. But which comes first is difficult to work out. we can’t look at ourselves without our thoughts turning to God , in whom ‘we live and move’. Acts 17:28 John Calvin

‘This skilful ordering of the universe is for us a sort of mirror in which we can contemplate God who is invisible’. John Calvin

For what can be known about God is plain to everyone, because God has shown it to them. Ever since the creation of the world his eternal power and divine nature invisible thought hey are, have been understood through the things he has made. Romans 1:19-20

The proofs of God’s existence… can predispose one to faith and help one to see that faith is not opposed to reason. Catholic Catechism

‘Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth; and God has placed in the human heart a desire to know the truth – in a word, to know himself – so that, by knowing and loving God, men and women may also come to fullness of truth about themselves….in the far reaches of the human heart there is a seed of desire and nostalgia for God.’ Philosophy is one of the noblest of human tasks’ which is ‘driven by the desire to discover the ultimate truth of existence….The truth made known to use by Revelation is neither the product not the consumption of an argument devised by human reason’ Pope John II, 1998, ‘Faith and Reason’

‘And the proper response to revelation is . . faith, faith being not an intellectual assent to general truths, but the decisive commitment of the whole person in active obedience to, and quiet trust in, the divine will apprehended as rightfully sovereign and utterly trustworthy at one and the same time.’

HH Farmer (1935)

Faith … is not a kind of stretched belief, or assent to a set of dogmas without sufficient evidence. It is the basic intuitive awareness of God experienced as actively approaching humanity and seeking the human response of acknowledgement and trust.

Peter Donovan

‘For Kierkegaard, because of human sinfulness and the whole otherness of God, God’s truth and human thought can never be smoothed out into a rational synthesis. Instead, the paradoxical truths of God’s self-revelation must be embraced in a leap of faith by the finite human mind.’ Grenz/Olsen

0 Comments