Handout – Christian Moral Principles

July 29, 2018

The Three Pillars of Christian Moral Principles

Peter Baron

The specification asks us to consider the relation between reason, tradition and Scripture in establishing Christian moral principles. It leaves out the fourth aspect – experience- by which we reflect upon our choices and actions and develop wisdom. I argue here that the Bible presents a causal sequence: God’s character reveals his holy characteristics particularly three – love, justice and truth. These are then incarnated in Jesus Christ who was ‘full of grace and truth’. Yet Christian moral principles which stem from the character of God also relate to the commandments of God. Again, contrary to what the specification implies, Jesus did not just command us to love. There are sixty-four commandments cited on the lips of Jesus in the Bible – you will find them in an extract in this section – and he reportedly said to his followers ‘if you love me you will obey my commandments’.

The three pillars of Christian moral principles are three characteristics of God, which Christians are called to show forth themselves. These three characteristics are encapsulated by the word ‘grace’ – God’s unconditional and generous outpouring of his gifts and love to each of us and also in the supreme act of making the world. The God of grace – overflowing goodness and generosity, exhibits three great characteristics which unite the Bible:

1. Love (Old Testament hesed)

2. Justice (Old Testament sedekah)

3. Truth (Old Testament emeth)

Let’s examine each in turn and then see how they unite in Jesus Christ, the word made flesh, who was ‘full of grace and truth,’ and also how these three moral principles unify our OCR specification. For justice is the particular concern of the liberationist and feminist theologian and love of the Situationist. All are embodied in the Person of Christ (Christian Thought) and revealed in the world (Knowledge of God). They make sense of the old law (the Torah or first five books of the Hebrew Bible – the Christian Old Testament) and the new law of the sermon on the Mount (Matthew 25).

Love (and Situation Ethics)

There is a golden thread of love which runs through the Old and New Testaments, We find it shown in the great epiphanies (revelations) of God to human beings. Perhaps the greatest of these is God’s revelation to Moses on Mount Sinai in Exodus 34: 6-12.

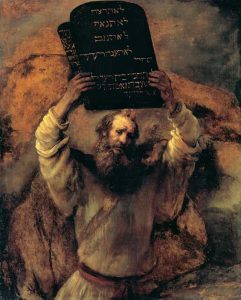

Moses is given the ten commandments – Rembrandt. But what is the relation between love and law?

5 Then the LORD came down in the cloud and stood there with Moses and proclaimed his name, the LORD. 6 And he passed in front of Moses, proclaiming, “The LORD, the LORD, the compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness,7 maintaining love to thousands, and forgiving wickedness, rebellion and sin. Yet he does not leave the guilty unpunished; he punishes the children and their children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation.”

8 Moses bowed to the ground at once and worshipped. 9 “Lord,” he said, “if I have found favour in your eyes, then let the Lord go with us. Although this is a stiff-necked people, forgive our wickedness and our sin, and take us as your inheritance.”

10 Then the LORD said: “I am making a covenant with you. Before all your people I will do wonders never before done in any nation in all the world. The people you live among will see how awesome is the work that I, the LORD, will do for you. 11 Obey what I command you today. (Exodus 34: 6-11)

God is here described as ‘abounding in love and faithfulness”. We will explain faithfulness as our third Christian Moral Principle – truth (Hebrew – emeth). Here we concentrate on hesed.

Hesed (Hebrew) means steadfast love, commitment love, unconditional love. It is the love of the covenant. We can also translate it as ‘favour’ as in verse 9, where Moses asks ‘have I found favour (hesed) in your eyes?” Hesed is the characteristic which God’s people need to show not just for God himself (reflecting the glory of God just as Moses’ face shone after his forty days on Mount Sinai with shekinah or glory) but for each other. And the ‘each other’ here is both friend and stranger.

We show, according to this great moral principle, generous love for the refugee and stranger in the land. Hesed then is a quality that moves someone to act for the benefit of someone else without considering “what’s in it for me?” It may also be translated as “loyal love.” Sometimes the emphasis is on “loyalty” and other times the emphasis is on “love.” Sometimes on ‘kindness’ and sometimes on ‘steadfastness”. It is a rich word which predates the New testament Greek word agape which we find incarnated in Jesus himself.

Notice that God’s revelation of his character comes first in Exodus 34. Then God makes the covenant – the treaty with the Jewish people which basically makes requirements of them as to how they should live. Law comes after love. For Christianity, Fletcher is surely right when he argues that love comes before and is superior to law.

The expression “God is love” (occurs twice in the New Testament: 1 John 4:8,16. Agape was also used by the early Christians to refer to the self-sacrificing love of God for humanity, which they were committed to reciprocating and practising towards God and to one another.

In his great work on the meaning of love, the Four Loves, CS Lewis reminds us that the Greeks had four words for love, but agape is the highest, a selfless love that is passionately committed to the well-being of others. Lewis calls it ‘gift-love’ and differentiates it from ‘need-love’.

“Need-love cries to God from our poverty; Gift-love longs to serve, or even to suffer for, God; Appreciative love says: “We give thanks to you for your great glory.” Need-love says of a woman “I cannot live without her”; Gift-love longs to give her happiness, comfort, protection – if possible, wealth; Appreciative love gazes and holds its breath and is silent, rejoices that such a wonder should exist even if not for him, will not be wholly dejected by losing her, would rather have it so than never to have seen her at all.” The Four Loves, p.17

Joseph Fletcher, the situationist also defines agape love in this way and sees it as the one absolute in Christianity – a principle, not a law, Indeed Fletcher is against laws as generally they produce unjust and unloving outcomes when tested in tricky situations. We see this most clearly in the Parable of the Good Samaritan, a kind of paradigm of the true nature of Christian love. It’s worth studying carefully (Luke 10:25-37).

The Good Samaritan (by Jan Wijnants) was helped by an ‘unclean’ stranger while the religious figures (like the teacher of the law who asks the question) are judged as unloving and disobedient to Leviticus 19:18.

25 On one occasion an expert in the law stood up to test Jesus. “Teacher,” he asked, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

26 “What is written in the Law?” he replied. “How do you read it?”

27 He answered, “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind’[a]; and, ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’”

28 “You have answered correctly,” Jesus replied. “Do this and you will live.”

29 But he wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, “And who is my neighbour?”

30 In reply Jesus said: “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he was attacked by robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead. 31 A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. 32 So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. 33 But a Samaritan, as he traveled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. 34 He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him. 35 The next day he took out two denarii[c] and gave them to the innkeeper. ‘Look after him,’ he said, ‘and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have.’

36 “Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?”

37 The expert in the law replied, “The one who had mercy on him.”

Jesus told him, “Go and do likewise.” (Luke 10:25-37)

Notice how the teacher of the law is part of the Temple hierarchy, is seeking to test Jesus. He is trying to get some interpretation of the golden rule, which presently we will describe as one of the foundational moral principles of the Bible. In answering a further question, ‘who is my neighbour’, Jesus tells a story which is at once open-ended and situational, because he ends with the simple command ‘go and do likewise’ meaning ‘go and do this kind of thing in these sorts of situations’. Yes, there is a situational element to Christian Moral Principles. The radicalness of the story is found in the detail.

1. Samaritans were despised as unclean as they had married outside the Jewish faith and had changed some rituals. Therefore it is the outsider who stoops to bind the man’s wounds

2. The Vicars, Bishops, Priests of their day (who of course are actually Jewish dignitaries, not Christian) pass by on the other side. Perhaps they are too busy. Or perhaps they don’t want to be dirtied by blood and exposed to danger. Cowardice and obsession with purity have nothing to do with Godly love. The teacher of the law who asks the question of Jesus is himself judged as it’s just this sort of person who doesn’t show love, or obey the Golden Rule of Leviticus 19:18.

3. The Samaritan goes way beyond the call of duty. He binds the wounds, places the man on his own donkey, and pays the health care bills. He shows how love and mercy mingle. Love is generous and hopes for the best, love is practical and always acts sacrificially with no concern for what it costs.

This is the radicalness of the Godly love Christians are called to incarnate. It is the love best shown forth by Jesus himself, as, in his own words, ‘greater love has no-one than this, that a person lay down his life for his friends’.

Justice (and Liberation Theology)

God is the God of righteousness and justice (Hebrew – sedekah). It implies we can also discern what is morally true and right and make judgments in difficult situations. However, although God exercises judgement based on his justice and righteousness, and ‘by no means clears the guilty’ (Exodus 20) nonetheless justice is always tempered with mercy. “Gracious is the Lord”, says the Psalmist, “and righteous, our God is merciful’. (Psalm 116:5). So we see again how these three values which define the character of God, love, justice and truth unite in his mercy (grace).

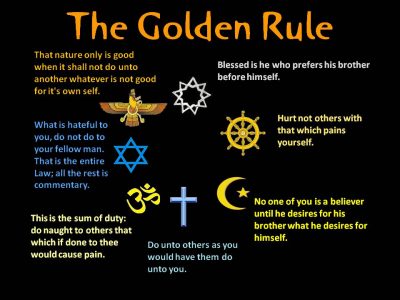

The Golden Rule of Leviticus 19:18 has echoes in all the great religions and philosophies of the world. Perhaps it is the one universal absolute.

A fundamental Christian Principle stems from this. It is the so-called Golden Rule ‘do to others as would have them do to you’ (Matthew 7:12). This echoes the great principle of Leviticus 19:18 ‘love your neighbour as yourself’. It is actually a principle of justice because it implies we treat everyone with strict equality and respect as if the other was myself, “Other’ here means any other – the stranger, the foreigner, the one I might be afraid of or instinctively want to shun. The golden rule echoes Kant’s great second formula of the categorical imperative “always treat people not simply as a means to an end but always also an end in themselves”. Even Mill claims the golden rule for his version of utilitarianism because it’s based on sympathy for others. Justice and utility, says Mill, demand we pursue concern for others.

As we exercise just judgments we do so in accordance with the truth. This is the moral obligation of all Christians. Christians are not pragmatic – moral principles do not shift and change. Of course, Joseph Fletcher has a point when he argues in Situation Ethics that we have to think pragmatically in the sense of ‘understand the implications for each situation’. We do this because justice is rarely simple. Moral laws conflict and are not absolute. The Bible says ‘thou shalt not kill” (Exodus 20) but also, we may kill in self-defence and can kill our enemies in times of war (see the book of Joshua for some brutal examples where Joshua wipes out whole cities including the children). Christian moral principles are absolute – Chrsitian moral rules are not.

Of course, in history the hermeneutics (interpretation) of these passages of the Bible has altered. People interpret according to preconceptions. For example, evangelical Protestants have had something of an obsession against ‘justification by works’. The Reformers such as Luther and Calvin stressed that we are only justified by grace – by the unmerited gift of God. Yet there is a problem here: there is a works-based element to Christian moral principles. What we do (our works) is important because it shows our own integrity – it reflects who we are. We incarnate values and principles because we follow the Christ who incarnates the morality (character) of God. But when the evangelicals read Matthew 25 and the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats, they encounter a problem. Jesus suggests we are judged by our actions to the poor and marginalised in whose face we should see the very face of Christ. Part of our embodiment of justice demands practical action. God’s judgment here is very definitely based on our ‘works’.

Another hermeneutic (interpretation) has developed with the advent of liberation theology and feminist theology in the 1960s. Rosemary Ruether writes of a golden thread of a prophetic-liberating tradition. The equality of women is fundamentally an issue of justice. Women must be set free from the bondage to patriarchy, its attitudes and its enslavements. The cause of liberation continues as we seek to eliminate inequalities in pay or the appalling instances of sex-trafficking, and violence against women, which still blight our world. Of course, the church itself as the agent of the new kingdom of peace and love must itself be reformed as the stains of patriarchy have mired its very soul.

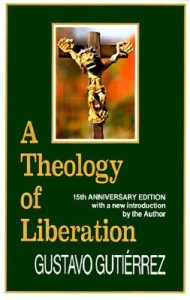

In a Theology of Liberation Guitterez explains the Old Testament inspiration for liberation theology.

Guiterrez’s book was written in 1971 and explains Christian poverty as an act of loving solidarity with the poor. God favours the poor.

“The prophets spoke of a kingdom of peace. But peace supposes the establishment of justice (Is 32:17), defence of the rights of the poor, punishment of the oppressor, a life without fear of being enslaved. A poorly understood spirituality has often led us to forget the human message, the power to change unjust social structures, that the eschatological promises contain—which does not mean, of course, that they contain nothing but social implications. The end of misery and exploitation will indicate that the kingdom has come; it will be here, according to Isaiah, when nobody “builds so that another may dwell, or plants so that another may eat,” and when each one “enjoys the work of his hands” (65:22). To fight for a just world where there will be no oppression or slavery or forced work will be a sign of the coming of the kingdom. Kingdom and social injustice are incompatible. In Christ “all God’s promises have their fulfilment” (2 Cor 1:20; cf. also Is 29:18-19; Mt 11:5; Lv 25:10; Lk 4:16-21).” Guitterez A Theology of Liberation

It is Jesus himself who announces this new age of justice and peace, echoing the prophets of old (Isaiah, Amos, Jeremiah).

“17the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was handed to Him. Unrolling it, He found the place where it was written: 18“The Spirit of the Lord is on Me, becauseHe has anointed Me to preach good news to the poor. He has sent Me to proclaim deliverance to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to release the oppressed, 19 to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.” (Luke 4:18 echoing Isaiah 61:1)

So we see in the person of the Christ more than just a good teacher of nice parable stories. We see a man of action, kissing lepers (Mark 2), welcoming a ritually unclean and hence outcast woman back into his family (Mark 5), healing the paralysed (Mark 2) and the blind receive their sight (Bartimaeus, Mark 10:46-52). No wonder the people around him are astonished as the signs fi the new age of the rule of God – the age of God’s hesed, his loving favour are revealed, and as Matthew says, “The blind receive sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and good news is preached to the poor”. (Matthew 11:5).

For Jesus’ followers, the practice of righteousness and justice is never optional. “Everyone who practises righteousness has been born of God”, says John (1 John 2:29). Jesus himself said. ‘by their fruits shall you know them’ and Christian moral principles bear fruit in actions for the poor, the oppressed, the homeless and the refugee.

Truth – emeth

God’s character has an integrity which makes his moral characteristics unchanging. This integrity is expressed in the Hebrew word emeth. God is abounding in steadfast love and truth (translated faithfulness in Exodus 34 above).

In Greek philosophy Alethia (truth) tends to refer to propositions which reflect objective reality. In Plato we seek for the Form of the good which lies beyond what we see. Both Plato and Aristotle speculate about this essence of truth and whether it is something we deduce a priori (Plato) or observe a posteriori (Aristotle). The issue is, what can we know as a true expression of the real?

To the Hebrew mind, truth is different – it is about character and hence is closely linked to the Christian Moral Principle of faithfulness. It is linked also to those moments of decision when I choose not to steal, or choose actively to give something to the homeless poor. Truth is a commitment word (a covenant word if you like). In my school or workplace I stand up against the bully, and I speak the truth in meetings when deception or nonsense is being told. Because I have integrity I am unafraid to speak with integrity. Ultimately the Christian’s integrity comes from God himself. I know God in relationship and so I know truth. I also, of course, know God’s commands which are part of his ‘truth’ but as we have argued above, commands come logically after God’s character. God’s commands require reason to interpret them, because these commands can never be absolute – for example, where two commands come into conflict we need to choose one which requires judgement of conscience (see the Ethics specification on conscience), and the use of reason.

Thomas Aquinas describes the four laws – where the eternal law pre-exists everything and is revealed first in the order of creation. Natural law in ethics is one of two ways God reveals this eternal law.

God’s truth is also present at the Creation. The last three letters of the creation story (Genesis 2:3) spell the word emeth. Translated it means “God created to do”. We find this idea reflected in Aquinas’ natural law where the eternal law (one of the four laws) is the truth (emeth) which underlies all things and then is revealed in the natural law (creation) and in the divine law (the Bible). The natural law, says Aquinas, is “the outworking of the eternal law in rational creatures”. And when in Christian Thought we study natural and revealed theology (the Knowledge of God section) we find echoes of this in Calvin’s sensus divinitatis, the sense of God we all possess. We are created in truth by God of truth and we are, to quote Augustine, “restless until we find our rest in God”.

The Psalmist says:

“For your loving-kindness (hesed) is before my eyes: and I have walked in your truth (emeth)”, (Psalm 26:3).

Truth is something we walk in – we live the truth. We walk faithfully with our God as Christians, just as Jesus faithfullyembodied and walked the values and way of God. As John reminds, us, Jesus was ‘full of grace and truth”. Jesus embodies the steadfast love and faithfulness of God himself. Jesus is God’s integrity.

So when Pilate asks of Jesus ‘what is truth’ he makes a category mistake. Truth is not something about propositions as in our debates about religious language. AJ Ayer and the emotivists (logical positivists – see issues in meta-ethcis or religious language) are profoundly wrong here. We should ask “who is truth?’, not ‘what is truth?’ and Jesus gives a resounding answer to this: “I am”. “I am the way, the truth and the life’ (John 14:6), so walk with me and in me and you will find life itself. So faithfulness, integrity, obedience, commitment, and yes, sometimes passion (anger at injustice and tears at the tomb of Lazarus) will accompany this way of Christian Moral Principles. The unfeeling (passionless) God debated in theology and believed in by such as Boethius does not seem to be the God of the Hebrew scriptures.

Love, justice and truth, these three Christian moral principles combine in the richest of words: grace. They are three pillars of Christian morality, a morality of principle, not of law.. The psalmist reminds us repeatedly: “Mercy and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed each other. (Psalm 85:10)”.

Further Reading

The Meaning of Hesed http://www.bible-researcher.com/chesed.html

The meaning of Grace http://www.bible-researcher.com/grace.html

The Meaning of Emeth https://hebrew4christians.com/Glossary/Word_of_the_Week/Archived/Emet/emet.html

0 Comments