Handout: Abortion and Ethical Theories

October 9, 2008

The Moral Status of the Foetus:

Philosophical Investigations into the Abortion issue

The Nature of the Problem

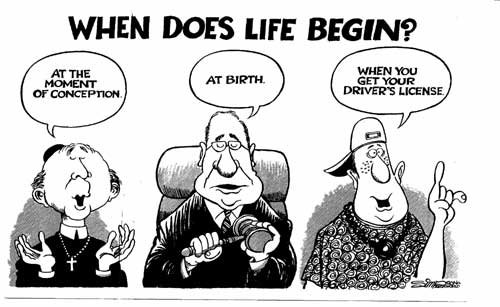

Click here for the current state of UK law on abortion. An embryo is defined as biological human life from 14 days to eight weeks. A foetus is defined as biological life from eight weeks to birth. Because the primitive streak emerges at 14 days the biological life from 0-14 days is now termed the pre-embryo – perhaps because of the advent of IVF treatments involving multiple pre-embryos. PB

Abortion has become a widespread and largely accepted feature of our society: today 25% of foetuses are aborted, and 8% of the total (16,460 in 2009) were teenage pregnancies. Interestingly, 11% were women having repeat abortions. Most (87%) occurred within the first thirteen weeks of pregnancy.2 Indeed, it is difficult to persuade doctors to perform very late abortions, unless there is overwhelming medical evidence, for example, that the mother’s life is at risk.

This seems to imply that most of us attribute a different moral status to the tiny foetus of thirteen weeks, versus the perfectly formed foetus of 23 weeks (the term was reduced in a 1990 amendment to the 1967 Act from 28 to 24 weeks in recognition that the age of viability – meaning the age of survivability – had come down with advances in post-natal care).

However, there seem to be a number of issues to address:

1. Are we right to attribute a different moral status to a foetus of 23 weeks? What might be the philosophical (rather than emotional) reasons for so doing?

2. Does a woman have an absolute right to abortion? From where does this right come?

3. Are there wider social issues surrounding abortion, such as the effects on the mental health of the mother, or the erosion of the sanctity of human life in other areas?

4. Can any of our key philosophical theories (Utilitarianism, Situation Ethics, Kantian Ethics, Natural Law or Virtue Ethics) help us at all?

5. How do we answer the metaphysical question – when does the foetus have human rights? It’s beyond science to answer this question as there is no significant fact we can agree upon to define personhood. Our views on this are determined by belief rather than some significant moment of transformation in foetal or embryonic life.

And of course, with the development of in vitro fertilization and embryo research (for example into stem cell treatments) there are ethical questions surrounding the moral status of the foetus outside as well as inside the womb.

Clarification of the question

At some point in the abortion debate we need to come to a decision about i. the issue of personhood and foetal status, and ii. the issue of women’s sexual and reproductive rights. We cannot avoid using our own beliefs about God, women’s equality, and autonomy, as well as moral feelings engendered by documentaries such as the Channel 4 documentary – Do foetuses feel pain? – which filmed the process of abortion.

There is no absolute right as the law stands for a woman to do what she likes with her own body and have abortion on demand.

This is because UK legislation is framed in such a way as to present abortion as a medicalissue. A pregnant woman must convince two doctors of the medical grounds for an abortion, either due to her own physical or mental health, or the health and future happiness of the baby. As one physician stated on one TV programme…….. “I am only thinking of the baby and its future welfare. I believe there is nothing worse than to come into this world as an unwanted child”.

Notice how this statement is framed in utilitarian terms. The child’s happiness (or the mother’s happiness) is paramount. But can we be certain that we can calculate this happiness or lack of it in the future? At best, as with all utilitarian calculations, we can present a hypothesis and hope we are right (of course our conscience will remain clear because there is no way of proving such speculations either way).

Notice how this statement is framed in utilitarian terms. The child’s happiness (or the mother’s happiness) is paramount. But can we be certain that we can calculate this happiness or lack of it in the future? At best, as with all utilitarian calculations, we can present a hypothesis and hope we are right (of course our conscience will remain clear because there is no way of proving such speculations either way).

Notice also that this calculation only includes two people’s happiness, the future life of a child and its mother. The feelings of the father, the grandmother, or even the implications for society generally are not considered.

Nor is it clear that the consequences for the mother’s future mental health are accurately considered.

Research published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry in January 2006 showed that woman who had abortions were twice as likely to have mental health problems and three times more likely to suffer from depression than those who had given birth or never been pregnant.

This has led to calls from some senior Psychiatrists for clearer guidelines on potential effects of abortion on women’s mental health.

(A word of warning here, in parenthesis. The fact that two things happen together does not necessarily mean they are causally linked. Women who had abortions may be more prone to depression because of other factors, such as the instability of their relationships, the presence of a background of abuse, broken homes etc. A much clearer link needs to be established to ascertain the validity of this argument, such as the women in question clearly attributing their mental health problems to an abortion).

In conclusion: the way the legislation is framed pushes us in a utilitarian direction, but it is arestricted utilitarian calculation because it only involves two people in it: mother and as yet unborn baby. Implicitly the baby is seen as that: a baby not a foetus, because a foetus in itself can have no rights (it is just an appendix until we accord it moral status).

But, to conclude, there is no women’s right to abortion guaranteed in law, only the right to consult two doctors who then assess each case on medical grounds.

Judith Jarvis Thomson and the violinist

Judith Thomson neatly avoids the central philosophical problem of the status of the foetus with a cleverly constructed argument from women’s rights.

Judith Thomson neatly avoids the central philosophical problem of the status of the foetus with a cleverly constructed argument from women’s rights.

She asks us to imagine we have woken up in hospital one day, finding ourselves attached to a famous violinist with kidney failure who needs to borrow our kidneys for the next nine months in order to stay alive. We have not consented to this situation, because we were kidnapped by friends of the violinist who needed to find someone with the same blood group. In this situation of complete dependency of one human being on another, wouldn’t we be justified in unplugging the line and walking out of the hospital?

“My own view is that even though you ought to let the violinist use your kidneys for the one hour he needs,we should not conclude that he has the right to do so. We should say that if you refuse, you are, like the boy who owns the chocolates and gives none away, self-centred and callous, indecent in fact, but not unjust…and so also for the mother and the unborn child”. Judith Jarvis Thomson (click her name for the whole chapter In Defense of Abortion pg 329)

It is an interesting analogy for a number of reasons. First of all it puts the question in a wider context: the violinist is a recognizable person who can talk to you and he has friends and supporters who would also remind you of the wider ethical considerations involving the death of a person which, we argued above, current UK law seems to ignore.

For there are, it seems to me, wider social considerations in a decision whether or not to abort, such as the views of the family, the possibility of the child bringing happiness to an infertile couple through adoption, and the implications of using abortion as a second line of contraception (does this make people more or less careful about conception and safe sex?).

However, it could be argued that Thomson has produced an analogy only to a situation where someone has had no choice over their pregnancy, such as rape. It’s also something of an exaggeration to imply that being pregnant is like lying in a hospital bed plugged in to a person we do not know or care about. For a start, most pregnant women carry on playing sport, presenting the weather on TV, doing the shopping even right up to the moment they go into hospital. The days when a woman was placed in confinement are over. And I think most women do care about their foetus (some obsessively so, going on strange diets and refusing to enter houses with cats present because there is some infinitessimally small chance of catching a disease from cats that causes miscarriages).

But her main point is well made. One person is growing a foetus inside her. One person faces all the risks of pregnancy and the probable pain of childbirth. One person is facing a lifetime of dependence or the choice of adoption with all its emotional heartache.

Her argument also illustrates how the law is framed in the UK. We do recognize a difference between dependent foetuses and those who have a chance of independent life. This is why the legal period for abortions continues to fall, and may yet fall further as the age of viability is now 22 weeks. She may also have hit on the reason most people accept abortions up to say 13 weeks, but dislike the idea of late abortions. They fear perhaps that a baby-like being might just survive outside the womb, and they feel this is somehow morally different.

If it can be established that a foetus has no more moral status than an appendix, then this strengthens Thomson’s case further. But her case does not depend on this because it is only an argument about the moral status of a dependent being.

The Church fights back: the theory of Natural Law

For a very full and interesting series of quotes on the Catholic Natural Law view, including several from Pope Benedict, click on this link: http://www.stdenischurch.org/ProLifeQuotes.pdf

Thomas Aquinas modelled his Summa Theologiae on Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics. For an action to be good, the kind it belongs to must not be bad, the circumstances must be appropriate, and the intention must be virtuous. So a bad intention can make a good act evil (to have an abortion, assuming we think this is good, could be spoiled by having one just because I want to go on holiday), but a good intention cannot make a bad act good (if I steal to help the poor it is still stealing, and if I have an abortion to save my family financial hardship it is still killing).

Thomas Aquinas modelled his Summa Theologiae on Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics. For an action to be good, the kind it belongs to must not be bad, the circumstances must be appropriate, and the intention must be virtuous. So a bad intention can make a good act evil (to have an abortion, assuming we think this is good, could be spoiled by having one just because I want to go on holiday), but a good intention cannot make a bad act good (if I steal to help the poor it is still stealing, and if I have an abortion to save my family financial hardship it is still killing).

Aquinas’ moral thinking shared the following characteristics with Aristotle:

- The good action is one which reason would approve. Even a conscience which is in error should bind us (though not necessarily excuse us, for example, if it is in conflict with the eternal law as we understand it).

- Everything has an ergon or natural function. The ergon of sex is reproduction. Aquinas takes this idea from Aristotle who saw the ultimate rational goal of human life to be eudaimonia, or the flourishing life which Aquinas terms ‘perfection’.

- As in Aristotelean thought, we use our reason to develop episteme or knowledge of the natural world, which produces sophia or understanding. Phronesis or practical wisdom is the application of our reason to moral choices we make. In applying our reason we are really working out the application of virtues, which to Aquinas would include the Christian virtues (faith, hope and charity, for example).

In two particular ways Aquinas develops Aristotelean thought, in one a direction which is undoubtedly helpful, and in another which is arguably unhelpful to the abortion debate.

Aquinas was keen to separate out the intention of an act from its consequences. He saw very clearly that good acts done from good intentions could have bad consequences. The example he discusses involved someone who kills an attacker in self-defence. The good intention is to defend oneself, the bad consequence, the death of the assailant.

From this helpful distinction between intention and consequence is derived the doctrine of double effect. The two effects of the action mentioned above, of defending oneself with the good intention of saving your life, are the preservation of life and the death of the attacker. What would be evil would be to intentionally kill someone in self-defence: here a bad intention makes the whole action wrong (unless of course you are a soldier or policeman acting on public authority, as for example, a policman might do in a “shooting incident”).

The Catholic Church has followed this doctrine. It is morally acceptable to act from a good intention (to save the mother’s life) even if there is both a good and bad consequence (the bad consequence being the death of the fetus). For details of Catholic Papal encyclicals (circulated letters) click on this link: http://www.papalencyclicals.net/ and try putting “abortion” or “sanctity of life” into the search engine.

Remember that there are three elements to Aquinas’ teaching on the goodness of a moral choice: intention, circumstances, and the kind of action involved.

Intentionally, we must act out of virtue, but the consequences are also important as the doctrine of double effect demonstrates. In some ways at this point Aquinas is asking us to think like a utilitarian, to ask whether the bad consequences outweigh the good, or vice versa, and to do a calculation. Instead of utilitarian happiness he employs the richer telos or goal ofeudamonia (best translated “flourishing”). In this way his thinking is not quite as absolute as we might think: he is recognizing that to hold to some good (thou shalt not kill) when there are bad effects, (you die, or another innocent person dies) is clearly wrong, and we need therefore to add a kind of phronesis or practical wisdom (you or I might say, plain common sense!). The aim is social flourishing – and to Aquinas anything that interferes with the sanctity of life is tantamount to committing social suicide.3

The difficulty arises, however, when we come to Aquinas’ definition of what kind of actions are bad, the third element of his trilogy of features (intention, consequence, kind).

Here we encounter the theory of the origin of the natural law. A pure Aristotelean would argue that reason defines the good and the bad in accordance with some concept of the virtuous mean. But as a Christian, Aquinas argued that the eternal law sets the standard of rightness, and that the two things are in fact not in conflict at all because God’s reason lies behind the design and patterning of the world and his intention is good. Antony Kenny sums up Aquinas’ view this way:

“It is a natural law, inborn in all rational creatures in the form of a natural tendency to pursue the behaviours and goals appropriate to them. The natural law is simply a sharing, by rational creatures, in the eternal law of God. It obliges us to love God and our neighbour, to accept the true faith, and to offer worship.” (Kenny, 1996:149)

This it seems to me is a development beyond Aristotle which has big philosophical problems (not least the assumption that God exists). Whereas Aristotelean thought seems quite content to relativise reason (and to have a debate for example, about which virtues to include or exclude) this move by Aquinas is in danger of absolutising reason and placing its definition in the hands of the Magisterium (the rule-making process of the Catholic Church).

Questioning the Natural Law approach

I would want to ask Aquinas these questions:

- What if the absolutes of the natural law are not as absolute as we first thought? Take the absolute “Thou shalt not kill”. We have already established it is okay to kill if the intention and one consequence is good. But the Hebrew word for kill is actually rasachwhich means “illegal killing judged harmful by the community“4. Generally, the Levitical law permits killing in times of war, self-defence, and as a penalty for crimes. The book of Exodus even implies a different moral status for a fetus, because if a woman is intentionally hurt by a man and as a result loses her baby, the husband must be compensated financially (Exodus 21: 22-3).

One Jewish Rabbi puts it this way;

“Jewish law is quite clear in its statement that an embryo is not reckoned a viable living thing until thirty days after its birth. One is not allowed to observe the Laws of Mourning for an expelled fetus. As a matter of fact, these laws are not applicable for a child who does not survive until his thirtieth day”. (Rabbi Balfour Brickner).5

- What if human sexual activity can have more than one ergon or function? For example, pleasure producing bonding between two people, as well as potential for reproduction?

Suppose it can be established (by observation, because we are Aristoteleans) that this function is actually primary (for two humans to mate successfully they must actually enjoy each other!).

Is this such an absurd proposition? And is there anything in the Bible to contradict this view?

- How is the natural law to be established? Even if we accept that God exists and his views are reasonable, the interpretation of these views still needs to occur in a specific time and place. Is it right that one man, the Pope, should have ultimate authority over this interpretative process? What if (God forbid!) he is wrong, or corrupt, or just overly male in his viewpoint?

A Protestant might reasonably argue (indeed in a way that’s true to Aquinas) that to establish the natural law we need a rational debate held by virtuous people with the best of intentions, examining everything (including the consequences of ruling that abortion is justified). After all, our worldview is logically prior to our perception: the fact that we now understand genetics and fetal development so much better inevitably determines how we view other more primitive ideas (such as the soul arriving at the moment of quickening).

We might note in passing that Aquinas believed the soul arrived after 40 days for the male and 90 days for the female!

So we come to the biggest objection to natural law. That the Catholic Church, acting from good intentions no doubt, has produced in its opposition to birth control a most evil outcome: the massive spread of AIDS through countries in Africa and South America (such that infection rates in for example Malawi are running at 50%). To consider the moral status of this policy, we need only consider an analogy.

An analogy might help

Suppose that next year there is a bird flu epidemic, and that this epidemic is proving to kill millions of people throughout Europe. I invent a surgical mask which, if worn when out in public or whilst kissing, eliminates the risk of catching the virus. The Church issues a decree stating that the natural function of the face is to breathe freely, and prohibits all believers from wearing the mask. Millions more die needlessly as the advice is followed, and thousands of children are orphaned. In churches across Europe they continue to pray for a miracle, and the old folks say “It must be the will of God”.

The argument against abortion from natural law, and the argument against contraception are, I suggest, the same argument. Both stem from the premise that the ergon of sex is to reproduce. Both stem from views about the sanctity of human life and the wrongness of preventing a potential human being, knit together by God from conception, from developing. Both stem from the obsession with finding a moment, a sacred ensoulment or a sacred conception, when a human person begins and has moral status.

Both have immoral consequences: the opposition to abortion entails the giving birth of unwanted or handicapped children, as well as suffering for the mother who might be tempted to go backstage to an old lady with knitting needles.

The opposition to contraception has the consequences of overpopulation and thespreading of a deadly disease.

The road to hell is paved with good intentions, and arguably, lousy philosophy. But because the concept of flourishing is partly relative to our cultural and gender perspective, we might argue that Natural law theory is open to the possibility that our views on such issues can change.

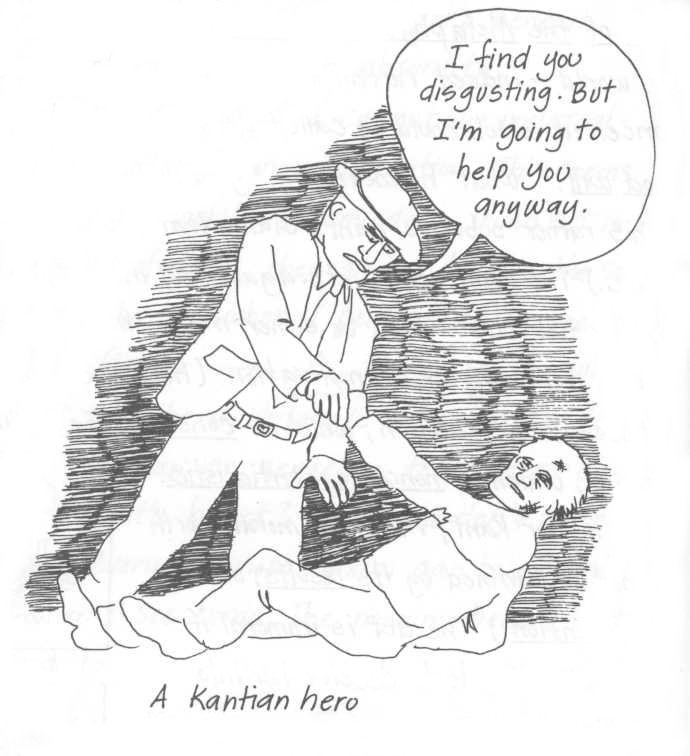

Kantian Ethics: a different approach

Kantian ethics is perhaps the hardest to grasp. Partly this is due to language: talking about the a priori synthetic or the categorical imperative presents us with a conceptual fog before we even start.

Kantian ethics is perhaps the hardest to grasp. Partly this is due to language: talking about the a priori synthetic or the categorical imperative presents us with a conceptual fog before we even start.

But I’m not sure the essence of Kant is so hard to grasp. Nor do I believe that many of the objections to Kantian ethics really stand up. So let’s try to reduce Kant to his raw elements before we apply his thinking to the issue of abortion.

The two great influences on Kant were Jean Jacques Rousseau and Isaac Newton. Rousseau inspired Kant to pursue the idea of the autonomous rational agent free from the impositions of the Church, free to choose the moral way by virtue of the exercise of pure reason, and able to universalise his judgements. Rousseau gave us the idea of the social contract, Kant, the idea of the legislature of moral beings existing in a kingdom of ends and coming up (impartially so to speak) with some idea of the common good and universal rights that guarantee this summum bonum.6

Newton’s approach

Newtonian science was something that applied, Kant thought, to the phenomenal world or world of matter and time and space. Newton gave us immutable laws such as the law of gravity which came to him as a result of an apple landing on his head. The world of Newtonian physics was a world of the a posteriori because laws come out of experience: the apple hits the head and always will do. It is also contingent because it depends on the natural world being as it is. On the moon, for example, gravity does not work the same way, and there are no trees recycling carbon dioxide, so if we visit the moon , as a contingent fact, I need to wear a space suit, breathe an oxygen cylinder, and I will find myself able to beat the long jump world record (a contingent record) by about three hundred yards.

If all this applied to the Newtonian phenomenal world, could it not also apply to the world ofvalues? Could there not also be a realm of pure reason which was derived a priori not from experience or desire, but simply by the application of reason willing what was good? And the good? The good was definable by applying the categorical imperative which gave us our concept of a right action, one which we ought to do.

Note that a little assumption has been slipped in here, namely that we will what is good, rather than what is evil. Is this argument not circular, in the sense that we assume that we will the good, which leads us to apply the categorical imperative, which then leads us to do the good?

Not exactly. Kant was attempting to objectify morality, to take it away from our subjective desires or selfish interests. He saw clearly, and rightly, that the natural law tradition had used sanctions to try and force us to act in a way that is contrary to our desires, by using fear and punishment. Natural law theory had imposed a conscience on us, but surely there were grounds for arguing that human beings, free from the chains of guilt and fear, could work out for themselves the difference between right and wrong?

This was Kant’s great insight: if we simply act on hypothetical imperatives, we act only from our desires. So we say “if I want to stay dry, I will need an umbrella or a lift from Auntie Maud”. Note that I don’t really need the “if” here. I can just say “I want to stay dry, so I’ll take an umbrella”. The point is this, it becomes a hypothetical statement because my moral compass is set as it were by my known desires. A hypothetical is also advisory, and so a weaker form of command, whereas a categorical is obligatory – a stronger unconditional”ought”.

But isn’t there another way to set the compass, a fixed point like the north pole which can give me straight guidance wherever I am and whatever I am faced with? After all, my desires are fluctuating and may be inconsistent or purely selfish.

Categorical imperative

That compass with a fixed point is the categorical imperative. What it gives us is a way of applying our reason to a situation so as to determine the rightness of our conduct in that specific situation. There is nothing abstract here; we can apply this imperative any where and any time; it is a priori because it is derivable from reason and it is contingent because it depends on the way the world is, with reason as the essential part of human beings, applied to contingent situations (ie real daily situations like what you and I might face).

Imagine, says Kant, that you are a person with a good will able to think rationally in every situation. How would you think?

Well first you would universalize your moral maxim, you would ask if anyone else was in the same situation as you whether you could reasonably will the same maxim for them.

Secondly, you would give equal rights to every human being to be taken seriously in the equation. There would be no second-class citizens in this kingdom: everyone’s interests and purposes would be treated equally. No-one would be a means to some end, but an end in themselves. I say please and thank you to the shopkeeper because they are a person in their own right with dignity and worthy of respect, they are not just a means to my getting food (even though they are clearly a means to that!).

Thirdly, Kant argued that we should imagine we are in a moral parliament, and everyone has one vote. We should act in such a way as this moral parliament would vote as a law binding all members, with everyone having one vote and not more than one vote.

So that is the way pure reason, unencumbered by desire, works out the maxims for the moral world. That’s how we get the moral law in the noumenal world: it requires reason, a respect for others and an ability to put ourselves in other people’s shoes.

Kant has sometimes been described as giving us the morality of common sense, the sort of common sense that decent, sympathetic people tend to have. Of course not everyone acts according to pure reason and the good will unencumbered by desire, but we can imagine what would happen if we did (and maybe commit ourselves to this better way, which to Kant sometimes implied acting out of duty rather than desire as if the two constantly conflict).

Of course, it is absurd to argue that because I want to do something good like help an old lady across the road it is not as morally pure as if I don’t want to do it but screw up my will and do it anyway!

But I don’t think this objection really holds, because as long as my desires are not in conflict with the categorical imperative it is perfectly okay to call them good. For Kant’s insight is to give us a way forward, as dignified, free individuals, to work out for ourselves what is meant by the good and the right. We really are free from the Church, our grandma, the Sun newspaper or any other external authority which might arise. And I would say, if only people since Kant had taken this way of deriving the right choice more seriously, we might not have got the twisted thinking of Mein Kampf or the disastrous misjudgement of the Iraqi war.

There is a lot more we can say about Kant, but it is right to call this a Copernican revolution in ethical thinking. Now ethics revolves around my practical reason (Kant’s term for it ispractical reason), not my selfish desires which can distort my view or the commands of God interpreted by a human authority. And Kantian ethics can be applied another way, to problems such as global warming, because the interests of future generations should have as much weight in my exercise of pure reason as the interests of the current generation. Kant woudl argue we cannot universalise collective suicide and so we ought not to destroy the environment.

Kant applied to abortion

How does all this apply to the issue of abortion? Well, if the fetus is not a person or given special status then we can’t really apply this directly to the unborn child. But we can still ask:

- If I was pregnant and the foetus was handicapped or even just unwanted, what would I decide to do? What end (telos) would I will? Or should anyone will? Can we give from a Kantian perspective full personhood rights to a foetus on the grounds that if I was that foetus, I wouldn’t want to be aborted? Is this a valid Kantian argument against abortion?

- If all human beings are ends in themselves, there is a case for saying, as J.S.Mill did, that I and I alone should be able to choose. As the mother is the rational autonomous being in question – it is arguably her choice that matters to a Kantian. But is it right to dispose of foetal life as a means to a mother’s happiness? Does this violate the principle of ends – never just use someone as a means, but always also as an end in themselves?

- If a legislature of rational moral agents was to meet together, considering all the consequences and the interests of those involved, what would this legislature will? Might it will a world without backstreet abortions, babies on doorsteps, single mums in poverty, and children with appalling handicaps? If the answer is yes to this, then there is a Kantian argument for abortion.

Kant helps us in a further way. By separating out emotion from reason he gives us a method of avoiding the sort of emotive debate we often find in the tabloid press. He warns us in a sense against moralizing out of gut feelings either for ourselves, or for our neighbour.

He reminds us that there is another way, and in so doing gives us a way forward to tackle complex moral issues whilst retaining our own dignity as moral agents not in thrall to anyone, as well as the dignity and interest of others.

He gives us a north pole, another way of setting the moral compass.

Citations

(1) A foetus stage “begins seven to eight weeks after fertilization of the egg, when the embryo assumes the basic shape of the newborn and all the organs are present. This stage continues until birth. The fetus is protected by a sac of amniotic fluid that also enables movement to occur. The placenta and umbilical cord are the sources of oxygen and nutrients and the means of waste elimination”. http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/foetus

(2) Daily Mail, May 25th 2011. Total abortions in 2009 were stable at around 190,000. Teenage abortions fell slightly.

(3) Summa Theologica II II section 64 states “every man is part of the community, and so, as such, he belongs to the community. Hence by killinghimself he injures the community”. By extension we might argue that by performing abortions we injure the community.

(4) rasach quoted in http://www.huppi.com/kangaroo/L-bibleforbids.htm

(5) Rabbi Bruckner quoted in http://www.huppi.com/kangaroo/L-bibleforbids.htm

(6) Kant wrote: “I am an inquirer by inclination. I feel a consuming thirst for knowledge, the unrest which goes with the desire to progress in it, and satisfaction at every advance in it. There was a time when I believed this constituted the honour of humanity, and I despised the people, who know nothing. Rousseau set me right about this. This binding prejudice disappeared. I learned to honour humanity, and I would find myself more useless than the common labourer if I did not believe that this attitude of mine can give worth to all others in establishing the rights of humanity.” Quoted in an excellent book review on Kant in http://www.phil.cam.ac.uk/~swb24/reviews/Kant.htm

Reading:

Level 1 readings (selected by PMB)

Judith Jarvis Thomson In Defense of Abortion in Robert E. Goodwin ed. Contemporary Political Philosophy (click here for her essay)

For Channel 4 factsheets on abortion go to:

http://www.channel4.com/search/?q=abortion

For papal encyclicals (the Natural Law view) click here and enter “abortion” into the search engine.

Level 2 readings (from Bristol University undergraduate course)

Abortion involves the intentional termination of a foetus. Is abortion morally permissible or impermissible? Much of the debate about this centres on the moral status of the foetus. Is the foetus a person? If so, is it a person from the moment of conception? If not, when does it become a person? If it is a person does it have a right to life? Or is it merely a potential person? Could it have a right to life in virtue of this potentiality? However, another aspect of the debate grants that the foetus has a right to life and then addresses the question of whether even so abortion might be morally permissible (such as in cases of rape, threats to the woman’s welfare, etc.). Another important issue concerns the basis of the woman’s right to choose. Some have recently argued that the debate does not make sense at all as a debate about rights and only makes sense as a debate about the sacred value of human life. Finally, is the state justified in prohibiting or restricting abortion even if it is morally impermissible?

Broady, B. Abortion and the Sanctity of Human Life

Davis, N.‘Abortion and Self-Defense’, Philosophy and Public Affairs (1984)

Devine, P. The Ethics of Homicide

Dworkin, R. Life’s Dominion

Feinberg (ed.), J. The Problem of Abortion

Marquis, D. ‘Why Abortion is Immoral’, Journal of Philosophy (1989)

Sumner, W. Abortion and Moral Theory

Thomson, J.J. ‘A Defense of Abortion’, Philosophy and Public Affairs (1971)

Tooley, M. Abortion and Infanticide

Warren, M.A. ‘On the Moral and Legal Status of Abortion’ Monist (1973)

0 Comments