Handout – Bonhoeffer and Moral Action

September 27, 2017

Dietrich Bonhoeffer: His Relevance Today

Understanding Bonhoeffer’s theology reminds us to consider:

1. Context – Bonhoeffer is described as a contextualist – his theology comes from his experience of suffering

2. Bible – remains an inspiration, but how do we interpret it?

3. Action (praxis) – are we for or against violence and under what circumstances? Bonhoefffer was implicated in the Stauffenberg bomb plot of 1944 to assassinate Hitler.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945)

When President George W. Bush ordered the invasion of Iraq, he invoked Dietrich Bonhoeffer to help justify his action on a visit to Germany in 2002. Some Bonhoeffer scholars were indignant, arguing that Bonhoeffer would have opposed the “war on terror.” In 1966 Joseph Fletcher honoured Bonhoeffer as a key inspiration for his book Situation Ethics; he argued that situation ethics meant that (among other things) abortion was permissible in some situations. The Presbyterian minister Paul Hill, on the other hand, murdered an abortionist in Florida in 1994, claiming that his violence was the same as Bonhoeffer’s resistance to the Nazi regime. In the 1960s, radical death-of-God theologians claimed that they were building on Bonhoeffer’s insights in Letters and Papers from Prison, but a couple of years ago the evangelical biographer Eric Metaxas told Christianity Today that Bonhoeffer was as orthodox as Saint Paul.

Has Bonhoeffer become all things to all men, beloved by all, everybody’s saint?

A. Context

We need to be wary of generalising from one context to another as George Bush did. Bonhoeffer writes in his Ethics: “The knowledge of Jesus Christ is a living reality. It is not something that is given once and for all, a static entity, something possessed. With every new day, therefore, the question arises, how, today, here, in this situation, can I remain and be preserved within this new life with God, with Jesus Christ?”

A key value in Bonhoeffer’s thought is responsibility : it is our responsibility to be there for others. Bonhoeffer describes the experience of responsibility as “the encounter with other human beings,” indicating that no one escapes this central ethical task. Everyone from parents to world leaders exists in relationships that afford daily opportunities to “be there for others.”

Bonhoeffer does indeed discuss the possibility that responsible action may in certain extraordinary situations take the form of a “free venture” that violates civil law or the law of God. But this form of responsible action is “extraordinary, the borderline case,” not to “be mistaken as the norm.” Responsibility is not something that one undertakes only in extreme circumstances; it names the entire life of discipleship lived in response to Christ and the claim of others.

1. Barmen Declaration 1934

The Confessing Church maintained a defiant resistance to Hitler’s decree that every German institution had to reorganise itself in line with National Socialist policies. Simply by its continued presence, the church defied the ideology that every person and every institution exists to serve the nation at the command of the Fuhrer.

“The Body of Christ takes up space on earth. That is a consequence of the Incarnation.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer

In Bonhoeffer’s context, insisting that the church takes up space was a political statement, susceptible to interpretation along classical Lutheran lines in which the secular ruler is entitled to obedience in everything except matters of faith, which may be interpreted in such a way that they take up very little space indeed. By 1938, most Confessing Church pastors had taken some form of loyalty oath to Hitler. For Bible-believing Christians there is a precedent for this, when Paul says in his letter to the Romans:

Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God. Romans 13:1

2. Experience in America

In July 1939 Dietrich Bonhoeffer left New York almost as soon as he had arrived there, to return to face the rising chaos in Germany. War was imminent. Bonhoeffer had already been hounded and silenced by the Nazi regime for his vocal opposition to its persecution of Jews. He had been offered safe haven by American friends, and had accepted it, only to change his mind.

“I have come to the conclusion that I made a mistake in coming to America. I shall have no right to take part in the restoration of Christian life in Germany after the war unless I share the trials of this time with my people.”

3. At Finkenwalde – the New Monasticism

The five founding principles of the new monasticism of the Finkenwalde community founded by Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Bonhoeffer introduced his fellow christians to the power of African-American church music—”a kind of music none of us had ever heard before,” Schoenherr said—via the 78-rpm records of black spirituals he brought back from a year at Union Theological Seminary in New York. “At Union,” Green noted, the young man who had trained in the rigorous systematic theology of the German academy “encountered for the first time the Social Gospel, the need for moral responsibility in this world.” Bonhoeffer saw this as a new kind of monasticism – of radical and costly devotion to Christ within community.

“The restoration of the church will surely come from a sort of new monasticism which has in common with the old only the uncompromising attitude of a life lived according to the Sermon on the Mount in the following of Christ. I believe it is now time to call people to this.” Letter to Karl-Friedrich Bonhoeffer (January 14, 1935)

He was also exposed to issues of race and civil rights. His American experience, Schoenherr said, produced a transformation that would play out for the remainder of his life. Its final outcome was expressed in what Schoenherr called “his last testament,” a letter that Bonhoeffer wrote the day after the failed attempt on Hitler. In the letter, Bonhoeffer explained for the first time his concept of the essential “this-worldliness” of Christianity, an idea which at that time seemed close to heresy. The authentic Christian witness, he argued, must reject the pursuit of personal salvation as its first aim, and focus instead on “sharing God’s sufferings in the world.” He wrote:

“I thought I could acquire faith by trying to live a holy life. I discovered later, and I am still discovering right up to this moment, that it is only by living completely in this world that one learns to have faith.”

This is where the work of Dietrich Bonhoeffer is so helpful in the contemporary conversation. He did not see a divide between social justice and fidelity to Scripture. Under the influence of Karl Barth, Bonhoeffer was fully committed to Jesus, as understood through the Bible interpreted by the Church, and to justice. He thought and lived outside of the categories that currently divide Christians into opposing political and theological camps. He did not avoid the hard work of redeeming society. Neither did he bless activities that clearly violated Christ’s call to justice.

He believed the Sermon on the Mount was not given to make us feel incapable, but to inspire us to respond redemptively to the inherent conflicts brought about by society. For him and the Finkenwalde seminarians, the Sermon on the Mount articulated a way of life together that is a very real goal for the Christ-follower.

This concept of “a sort of new monasticism” took form during the first months in the new seminary community. We glimpse an important component of Bonhoeffer’s emerging thought in Discipleship, which he wrote during the two years Finkenwalde operated. In this work he contrasts cheap grace and costly grace. Cheap grace “is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross.” Costly grace is the grace of the gospel: it costs people their lives. Bonhoeffer emphasises:

“Nothing can be cheap to us which is costly to God.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Discipleship, page 45

Further reading: https://www.baylor.edu/content/services/document.php/116020.pdf

4. Arrest and Death

Back in Germany, Bonhoeffer joined the small resistance movement. One of the leaders was Hans von Dohnanyi, who was married to Bonhoeffer’s sister. Soon Bonhoeffer, an avowed pacifist, agreed to join a conspiracy whose aim was to assassinate Hitler. In the spring of 1943, after using his church contacts to help a group of 14 Jews escape to Switzerland, Bonhoeffer was arrested by the Gestapo.

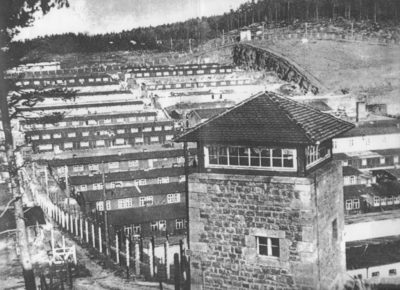

Dietrich Bonhoeffer spent his last nine months in Flossenburg concentration camp before being murdered by the Nazis just eleven days before he camp was liberated.

For two years he waited in prison, quietly ministering to his fellow prisoners, writing a series of letters that survive as both a poignant testament to faith and a fragmented vision for a viable post-war Christianity. On July 20, 1944, the long-planned attempt against Hitler was finally made; a bomb smuggled into the Fuhrer’s headquarters exploded but failed to kill him. There followed a vicious round of retribution in which some 5,000 people were killed: some summarily shot, others repeatedly strangled and revived, their agonies filmed for Hitler’s pleasure. One of those condemned to die was Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Over the next few months, he was moved first to the Gestapo prison in Berlin, then to Buchenwald, then to the concentration camp at Flossenburg. Finally, on April 9, 1945, 11 days before Flossenburg was liberated by U.S. troops, Bonhoeffer was hanged. He was 39 years old. His last act was to lead and share in a liturgy of communion with his fellow prisoners. His last words, according to one who survived, were better than scripted: This is the end, for me the beginning of life.

Most German church leaders considered Bonhoeffer’s criticism of the Nazi regime to be unpatriotic, Schoenherr said. Some even suggested that Hitler was God’s instrument, a scourge that must be endured. “Bonhoeffer vehemently rejected these views, and bitterly deplored the church’s paralysis,” said Klemens von Klemperer, professor emeritus of history at Smith College. For Bonhoeffer, von Klemperer added,

“The this-worldliness of Christianity is crucial. ‘The church stands, not at the boundaries where human powers give out, but in the middle of the village.’ Thus the sharpness of his condemnation of the church’s failure.” Klemens von Klemperer

Some of Bonhoeffer’s final letters offer us hope for a new future:

“The world lives by the blessing of God and of the righteous and thus has a future. Blessing means laying one’s hands on something and saying, Despite everything, you belong to God. This is what we do with the world that inflicts such suffering on us. We do not abandon it; we do not repudiate, despise or condemn it. Instead we call it back to God, we give it hope, we lay our hand on it and say: May God’s blessing come upon you, may God renew you; be blessed, world created by God, you who belong to your Creator and Redeemer.”

B. Bonhoeffer’s Theology of Resistance

Bonhoeffer had written, in 1932, that the Sermon on the Mount made Christian pacifism “self-evident” to him. How did he come to embrace the resort to violence? Did his ethical views radically change? Did he simply abandon them?

1. Responsible Action as Duty

Von Klemperer argues that “What moved him to action was his awareness of a Christian’s paramount duty to act responsibly in the world—even when that action comes into conflict with conventional ethics. It may mean lying, breaking the law; even murder can be justified. Bonhoeffer wrote this in the late 1920s.”

Victoria Barnett, of the Churches Center for Theology and Public Policy, quoted a letter Bonhoeffer’s brother and co-conspirator Klaus wrote from prison: “I am not afraid of being hanged, but I don’t want to see those faces”—i.e., those of his torturers—”again. So much depravity. I would rather die. I have seen the devil, and I can’t forget it.” Barnet comments:

“The question that Bonhoeffer wrestled with was how to resist this kind of evil. How to retain his humanity in the face of people who seem utterly devoid of humanity.”

Conventional tactics would not be enough. In 1942, Bonhoeffer wrote a letter to his close friends in the resistance, describing their situation as he perceived it. After ten years, he wrote, “the great masquerade of evil has played havoc with all our ethical concepts.” The standard responses to evil reason, principle, conscience, freedom, and virtue, had all failed in the crisis of Nazi tyranny. For Bonhoeffer, said Clifford Green, professor of theology at the University of Hartford, there remained only one moral weapon that could endure: what Bonhoeffer calls “free responsibility.” Bonhoeffer asks:

“Who stands fast? Only the one for whom the final standard is not his reason, his principles, his conscience, his freedom, his virtue, but who is ready to sacrifice all these, when in faith and sole allegiance to God he is called to obedient and responsible action.”

“According to Bonhoeffer,” Green explained, “in such a situation the Christian must reject the traditional consideration of good and evil, and instead try to determine what is the will of God.”

Answerable only to God is a concept that sounds frightening to secular ears, particularly in an age when religiously motivated violence, suicide bombings, abortion-clinic attacks is an all-too-frequent occurrence.

2. Ethical Maturity and Courage

But to Bonhoeffer, moral fanaticism was only one more of those conventional ethical responses, both easily corruptible and doomed to failure in a crisis. The fanatic, he wrote, “thinks that his single-minded principles qualify him to do battle with the powers of evil; but like a bull he rushes at the red cloak instead of at the person who is holding it.”

And if “free responsibility” sounds too much like courting anarchy, Bonhoeffer pointed out, it can be equally disastrous to rely on the rule of law. The obedient German whose excuse was, I was only following orders, “misjudged the world; he did not realise that his submissiveness and self-sacrifice could be exploited for evil ends.”

Bonhoeffer’s, it would seem, is an argument for ethical maturity and courage enough to risk setting aside abstract solutions when concrete circumstances demand it.

“For Bonhoeffer, ethics is a matter of history and blood,” said James H. Evans, president of Colgate Rochester Divinity School.

“There is no universal ethics. There are no principles to resort to. Yesterday’s ethical decisions can’t be prescriptive every situation is unique. You have to seek God’s will anew each day. It is through this freedom that Christians become creative in ethical actions.”

Moral authority for this creativity, it follows, has to be earned. Evans, an expert on African-American theology, noted that both Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther King were demonstrably committed, to the limit of their lives, “to causes that could justifiably be called not their own,” both having come from comfortable middle-class backgrounds. Furthermore, “both were deeply rooted in spiritual connectedness. It was only by being in touch with God that you could reduce the risk of ethical decisions.”

3. Contextual, Not Relativistic

J. Deotis Roberts, professor of Christian theology at Duke University, also brought up the importance of “the values that people draw on when they make ethical decisions.” Roberts argues,

“Bonhoeffer was not a situationalist or a relativist but a contextualist,” the difference being that “contextual is thoughtful, careful, prayerful, based in long, deep experience.” John Roberts

Within his particular context, Roberts noted, King clung unequivocally to his own non-violent roots, influenced by both his theological training (during which he had read Bonhoeffer) and the powerful example of Mahatma Gandhi. “Put these together,” Roberts said, “and non-violence became a formal absolute principle for him, consistent with natural and divine law. It was non- negotiable. He was consistent in emphasising this, even when non-violence didn’t work. This was King’s dilemma.”

Compare and contrast the theology of Bonhoeffer with that of Dr Martin Luther King, here preparing for the march to Selma.

King’s context, of course, was markedly different from Bonhoeffer’s. While Bonhoeffer faced what Roberts called “a kingdom of evil,” King, noted John de Gruchy, lived in a democracy: “The problem was the democracy wasn’t working.” De Gruchy, a professor of religion at the University of Cape Town who was active in the South African anti-apartheid movement, outlined parallels between Bonhoeffer and Nelson Mandela, long-time leader of the African National Congress. Although, “the comparison must not be unduly forced,” de Gruchy said.

The ANC, since its founding in 1912, had been committed to non-violence, he noted, for both strategic and moral reasons. “Peaceful resistance had again and again been rebuffed, met with increasing force. It was only when all else failed . . . that the decision was taken to embark on violent forms of political struggle. ‘We did not choose,’ Mandela told the court when he was tried for treason in 1961; ‘The government gave us no choice.’ He felt morally obliged to do what he did. But he had an acute awareness of the need for control of the violence that would be unleashed, of the danger of all-out civil war. The cycle of violence had to be broken, not perpetuated.

4. Resistance as a Last Resort

De Gruchy went on to emphasise, in his concluding remarks, “the need for careful contextual analysis, and not romanticising violent resistance.” Both Bonhoeffer and Mandela, he said, “carefully weighed the contexts of their actions, and were willing to accept responsibility for them, and for their consequences.” Bonhoeffer writes:

“Only those genuinely committed to peacemaking have the moral authority to resort to violence as a last resort.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Ought there to be other considerations as well? Nathan Stoltzfus, professor of history at Florida State University, began his talk by paraphrasing the Dalai Lama, “who said that although the use of violence may be all right morally, it is not effective.” Bonhoeffer himself, Stoltzfus noted, wrote of the ethical significance of success. Bonhoeffer wrote:

“The ultimate question for a responsible man to ask is not how he is to extricate himself heroically from the affair, but how the coming generation is to live.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Were there non-violent avenues that could have been a more effective means of resistance against Hitler? Stoltzfus pointed to the case of intermarried German women, “non-Jewish women who rescued their Jewish partners from death by refusing to divorce or isolate them and leave them vulnerable.” While others acquiesced to ostracise or even denounce their Jewish neighbours, he explained, “These women had the courage to resist Nazi authority openly. In this sense, they ‘stood fast’ like Bonhoeffer but their methods were much different. And they were effective.”

This effectiveness, Stoltzfus said, points to a larger possibility:

“The Nazi regime may not have advanced to Holocaust in the absence of social acceptance. The Nazis built on social norms and social pressures. It was the passivity of the large majority of Germans that gave the government the green light.”

By 1938, it was too late for nonviolent resistance. “The ‘community’ between the people and Hitler was strong,” Stoltzfus said. “Brute force was the standard method of control.”

“As Bonhoeffer moved more deeply into the conspiracy,” concurred Wayne Whitson Floyd,

“He realised that the time for any moral solution to Hitler had passed. He and other responsible Germans were faced with only immoral choices: to let it happen, or to renounce the principle of non-violence. Guilt would have to be incurred.” Wayne Whitson Floyd

Conclusion

Wayne Floyd, who is canon theologian at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Cathedral in Harrisburg, argued that the decision for violence does represent a profound failure for Bonhoeffer.

“For Bonhoeffer, violence is always evidence of human brokenness,” he said. “Concern for the ethics of violence is not a boundary issue. Rather, it touches on our most basic assumption about what it means to be human.” Wayne Whitson Floyd

Clear in Bonhoeffer’s early writing, Floyd said, is that, “What is extraordinary about the Christian story is the command to love our enemies as God on the cross did, accepting the punishment due to our enemy, with our greatest concern being for the enemy’s redemption.” This concept is, for Bonhoeffer, “the absolute centre of Christianity. . . . It is the way by which we affirm the other as of the very same value as ourselves. Bonhoeffer leaves no room for ambiguity” on this point, Floyd said. ”

The human desire for revenge is stronger than any other, and giving up that desire is probably the hardest sacrifice we are asked to make, but there can be no retributive justice. This is the cost of discipleship.

“He never attempted to justify his action,” Floyd concluded. In fact, Bonhoeffer told friends that he considered that his participation in the conspiracy had made him unfit for the pulpit should he survive the war.

On our blood lies the heavy guilt

Of the useless servant, cast out into darkness, he sings, in Robert Hatten’s libretto.

I cannot escape guilt by evading my responsibility.

And, finally,

It is better to do evil than to be evil.

These lines are Bonhoeffer’s own, Hatten had noted a few nights earlier, outside the room where the orchestra was playing. The last “is more of a concession than a proclamation,” he had said.

“He is throwing himself on God’s mercy.”

Exercise: using this quizlet, test yourself in pairs on Bonhoeffer’s theology of radical life and practical action. https://quizlet.com/212122507/christian-moral-action-flash-cards/

Source Penn Hill University http://news.psu.edu/story/140578/2000/05/01/research/bonhoeffer%E2%80%99s-dilemma

0 Comments