Handout: Utilitarianism

October 18, 2008

Utilitarianism

© Peter Baron 2015

This handout is a much reduced summary of the detailed treatment of three forms of utilitarianism (Bentham, Mill and Singer) in my book Utilitarianism and Situation Ethics.

Introduction

Utility means “usefulness”, as the claim of the Utilitarian philosophers such as Bentham ((1748-1832) and Mill (1806-1873) is that their philosophy is useful for two reasons: it helps define what is good and it helps us make decisions on a personal level by examining the consequences of our choices, and on a collective level by giving us an indicator of welfare for society.

There are three features of utilitarian philosophy:

- Empirical

- Teleological

- Naturalistic

Utilitarianism is an empirical philosophy because it claims happiness or pleasure can be measured and calculated and then applied to real-life situations. It is teleological because the calculation concerns consequences which result from pursuing the end or telos of pleasure or happiness. And thirdly it is naturalistic because an “ought” is derived from an “is”: what “is” the happiest state of affairs is the one we “ought” to create. “Goodness” becomes a property of something in the natural world which utilitarians believe we can measure, that something being pleasure (the hedonistic utilitarians) or happiness (the act and rule utilitarians) or preferences (the preference utilitarians like Sidgwick and Singer).

Forms of Utilitarianism

In this section we will consider two classical utilitarians who emerged in an era of social reform and revolution: Jeremy

Bentham and John Stuart Mill. Some people have classified Bentham as an egoistic act utilitarian, and Mill as a rather snobbish rule utilitarian. Yet as MacIntyre points out, neither Bentham nor Mill are consistent utilitarians (MacIntyre 1974:232), for Bentham appears to espouse a theory of psychological hedonism (as we shall see), but at the same time was a social reformer who, amongst other things, designed a special, more humane type of prison called a Panopticon (see picture).

And in his famous essay, Mill appears to start out as an act utilitarian who believes pleasures can be designated as either “higher” or “lower” depending on our nobleness of character. He later argues that virtue is a key means to obtaining happiness – the virtue of sacrificing one’s own happiness to gain the happiness of others, for example, which can produce a greater sense of contentment. Then in the final section on justice he appears to defend the idea of rights and rules as being principles of utility.

To explore this link between Aristotelean virtue and Mill’s view of happiness as requiring some traits of character, follow this link for an excellent discussion by Martha Nussbaum, or go to the extract here on Wordsworth’s The Happy Warrior.

http://www.utilitarian.net/jsmill/about/20040322.htm

The Logic of Utilitarianism

Here in outline is the logic of the utilitarian position. It’s important to see that the utilitarians are trying to find an objective way of advancing social welfare and for judging between competing claims. This principle is called “the principle of utility” or the “greatest happiness principle”.

- There is an empirical (measurable) way to calculate goodness – goodness has an objective basis.

- This objective basis is the maximisation of happiness – something is good if it maximises the greatest happiness of the greatest number.

- There is a radical equality in this – whether you’re the Queen or a homeless person, “everyone is to count for one and no-one more than one” (Bentham).

- If a good act is one that maximises pleasure over pain, how do we measure pleasure?

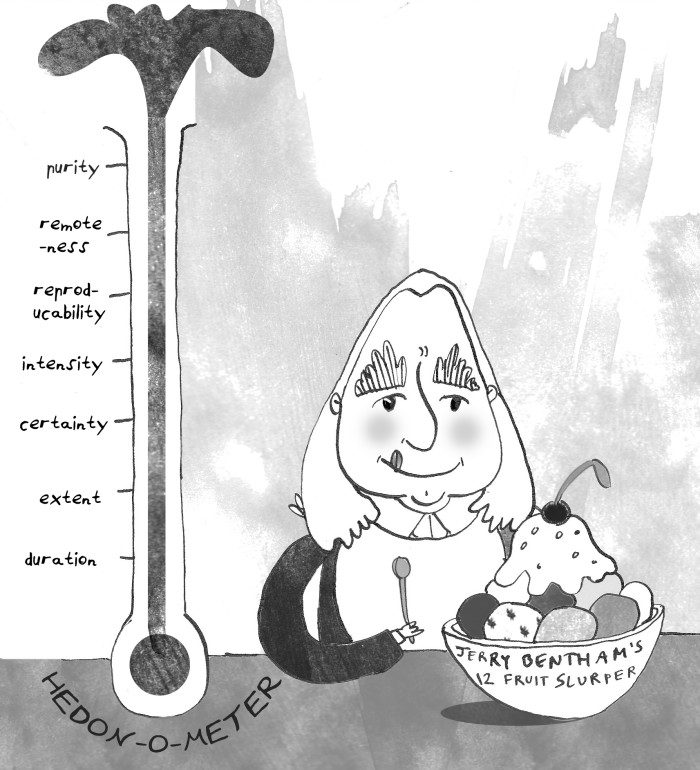

- Bentham (a hedonic act utilitarian) thought we could measure the hedons (pleasure units) we get from an action.

- He calls this the hedonic calculus (acronym P.R.R.I.C.E.D. Purity Remoteness Richness IntensityCertainty Extent Duration).

- The problem is – how do I know my hedon equals your hedon?

- Mill objected to this idea – he thought his poetry hedon was worth more than your football hedon. So he argued for higher and lower pleasures, of the mind and body respectively.

- He also worried about the majority voting to oppress (lynch) the minority.

- So Mill argues that rights and justice are necessary to guarantee a happy world – if we all have rights we’ll be happier.

- The problem of calculating pleasure hedons also meant it was easier to follow rules – which are the accumulated wisdom of everyone before you.

- Except when two rules conflict – then we can make an act utilitarian calculation (conflicts are a problem for nearly all moral theories. Should I lie to save a friend’s reputation?).

- Singer’s preference utilitarianism includes all feeling species in the calculation and seeks to maximise preferences and interests. (But see my handout – Singer isn’t very consistent on this and ends up arguing for preferences for superior beings and pleasure/pain calculation -by someone else – for inferior beings).

How do we measure happiness?

A central problem is how we measure pleasure or happiness, because it seems a subjective concept to ask how much pleasure out of ten you’re getting from eating that Mars Bar. Is sensuous pleasure really of equal hedonic value to listening to Mozart? Bentham thought so, but Mill disagreed. Click here to read this short but excellent introduction to Bentham – he is treated much too briefly by textbooks.

Happiness is an elusive concept. To Bentham the end was pleasure, and pleasure and happiness appear to be linked in

Bentham’s thought. He famously declared:

“Nature has placed mankind under two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them to point out what we ought to do as well as determine what we should do.”Jeremy Bentham

Bentham seems to be arguing for an idea of psychological motivation, but it is by no means clear that in pursuing just pleasure alone, I will have a fulfilled life.

To begin with, are all pleasures of equal value? Is it of equal value that I read poetry or eat jelly snakes at 2p each? Suppose I attach myself to a pleasure machine, as JJ Smart suggests (1994: ), inserting electrodes in my brain which stimulate all sorts of pleasure without my actually moving a muscle in effort. Would we consider this desirable and good? And what about the soma pill which is available in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World? Do we think it right that people could have “happy pills” which produce a pleasurable state without the normal processes of struggle and achievement?

Bentham declared confidently that the pleasure of push-pin, a game involving firing a ball up a wooden board and counting the scores according to the ring of nails it lands in, is as good as poetry. In today’s culture, playing computer games is as valuable as reading Dickens.

“Prejudice apart, the game of push-pin is of equal value with the arts and sciences of music and poetry. If the game of push-pin furnishes more pleasure, it is more valuable than either”. Jeremy Bentham

Mill disagreed and spent quite a few pages in the second section of his essay arguing for “higher” and “lower” pleasures. Even here Mill is not entirely consistent, as he flits effortlessly in his essay between references to pleasure and happiness, as if they were identical. They are not: pleasure is commonly thought of as a sensation, whereas happiness is more a long-term state, something closer to contentment.

So Mill begins by saying “pleasure, and freedom from pain, are the only things desirable as ends” but then also says “happiness is…moments of rapture…in an existence of few and transitory pains, many and various pleasures, with a predominance of the active over the passive..not to expect more from life than it is capable of bestowing” (p144). Here he moves beyond pleasure as a psychological state, and talks about activity and expectations, both very different things to pleasure as feeling.

Mill argued that if someone experienced the pleasure of poetry (as he had, reading Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads) and compared it with the pleasure of computer games (for example), then that person, who alone is competent to judge, would always prefer reading Wordsworth. An educated, intelligent person would never swop places with a fool, argued Mill, so there must be some pleasures that are superior to others.

“It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied”. J.S.Mill

Is Mill just being arrogant and elitist? What would the aficionados of computer games say to this argument? Whatever we think of this question, it is clear that Mill’s point, that pleasure is not a simple idea as Bentham implied, is surely correct, and that the calculation of pleasures is far from a simple process.

Exercise 1: on the website is an article by John Naish. He argues that happiness is not a very easy goal to pursue in and of itself, because happiness is often a by-product of doing or pursuing something else (which may be what Mill is driving at in the quote above). Evaluate the argument in this article.

Exercise 2: Bentham argued for a hedonic calculus, wherein pleasure can be measured by seven criteria. These seven are intensity, duration, certainty, propinquity, fecundity , purity and extent. For an exercise and an explanation, go to Exercise 2 Not yet loaded up! on the website.

Further reading:

Bentham’s Hedonic Calculus explained and evaluated.

Bentham’s Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789)

Consequentialism: the end justifies the means

Bernard Williams and others have criticised the utiltiarians for destroying moral integrity on the back of a cold calculation. If on reflection it maximises social happiness to keep ten per cent enslaved, then a strict utilitarian should say it’s morally right. But is it?

Classical utilitarians argue that an act is morally right if it maximises the good (pleasure or happiness, depending) and minimises the pain. For an individual this means making a calculation of likely consequences and choosing the best outcome. For society it means aggregating all members of society and making a policy choice which maximises the happiness of the largest number of people. As Mill put it, defending himself against the charge that utilitarianism was a selfish philosophy, it was concerned “not with the agent’s own happiness,but with the greatest happiness altogether” (p142).

Notice that the past is irrelevant to this calculation. Only present and future happiness matter. So if I have promised to go shopping for my mother today (past) and then it is clear that my students would like me to take them out to coffee (future), then the students claim wins in this calculation, because a past promise counts for nothing.

So utilitarianism reduces rightness or wrongness simply to consequences. Past history or the intrinsic nature of the act have become morally irrelevant. I can make as many promises as I like, and I can tell as many lies as I like (which Kant would argue is intrinsically wrong because it destroys the logic of promise-keeping: for a promise to be a promise it has to be kept!). To a natural law theorist this seems a rather narrow view of goodness. Are there not other goods (like life, education, society, to mention three that Aquinas believed were “primary goods”)? Indeed Mill implies in his essay that education is a good, as it helps us distinguish between the higher and lower pleasures!

Aggregation is also not as simple as we might think. If we are trying to determine the happiness which results from an action, how far into the future do we go? Do we include future generations, for example in the calculation whether to buy a gass-guzzling sports car to please my wife, when I know the carbon imprint will be much greater than a Daewoo Matiz?

And how do I weigh your claims to happiness against someone else’s unhappiness? Bentham’s hedonic calculus, as an attempt to measure pleasure in hedons or utils, seems doomed to failure for two reasons: first, because the “hedon” for pleasure is about as meaningful as having “bytes” for love. Such states as happiness and love, both of which Kant believed belonged to the non-measurable noumenal world, can’t be reducible to a unit, because the value of that unit is so subjective. And second, because my happiness versus your misery doesn’t appear to be a very moral calculation. Why should I have a right to inflict any misery on you at all? If I do, shouldn’t I just refrain from making that choice?

There is a bigger problem with this sort of consequentialist theory, produced by the age-old philosophical dilemma: does the end ever justify the means? Joseph Fletcher thought so, and wrote in Situation Ethics, “the end justifies the means, and nothing else”, as if we were being stupid if we questioned this idea. Surely to torture a suspect when a bomb is ticking in a bus in Whitehall (the means) is justified if lives are saved (the end)?

Solzenitsyn hauntingly evoked life in the gulag camps in One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch. Ten million died.

However consider the following argument in Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon (1940). A former revolutionary in Russia is arrested for doubting the idea that the mass murders of the Stalin era, in which an estimated ten million Russians died, was

actually justified:

“Acting consequentially in the interests of the coming generations, we have laid such terrible privations on the present one that its present average length of life is shortened by a quarter”. Koestler, Darkness at Noon

Utilitarian arguments in this way can explain all sorts of moral fanaticism, the fanaticism of the Nazi murder squads and the Stalinist secret police, and the brutalism of Amon Goth, commandant of Auschwitz, so chillingly portrayed in the movie Schindler’s List.

Bernard Williams, the English philosopher who died in 2004 (pictured), produced two dilemmas which goes to the heart of this difficulty that consequentialism can ride roughshod over human rights and create some immoral outcomes.

Example 1 George is a scientist who is out of work. He is offered a job in a laboratory which does research into chemical and biological weapons. George is strongly opposed to the manufacture of chemical and biological weapons. If he does not take the job, his wife and his children will suffer. And if he does not take the job, it will be given to someone else who will pursue the research with fewer inhibitions. Should he take the job?

Example 2 Jim is an explorer who stumbles into a South American village where 20 Indians are about to be shot. The captain says that as a mark of honour to Jim as a guest, he will be invited to shoot one of the Indians, and the other 19 will be set free. If Jim refuses, all 20 Indians will be shot. What should Jim do?

“To these dilemmas, it seems to me that utilitarianism replies, in the first case, that George should accept the job, and in the second that Jim should kill the Indian. Not only does utilitarianism give us these answers, but, if the situations are essentially as described and there are no further special features, it regards them, it seems to me, as obviously right answers.” (Smart and Williams, 1994)

“A feature of utilitarianism is that it cuts out a kind of consideration which for some others makes a difference to what they feel about such cases: a consideration involving the idea, as we might first and very simply put it, that each of us is specially responsible for what he does, rather than for what other people do. This is an idea closely connected with the value of integrity.” (Bernard Williams, 1994)

Williams is arguing that utilitarianism robs us of something essential to our character: our commitment to certain ideals and values which are quite independent of consequences, values such as truth-telling and the sacredness of human life. If you ask me to act outside of my character then you are asking me to do something impossible: to be someone else.

Further:

JCC Smart’s reply to Williams “Integrity and squeamishness”.

An interesting discussion of these two cases on a philosophy blog.

Act and rule utilitarianism

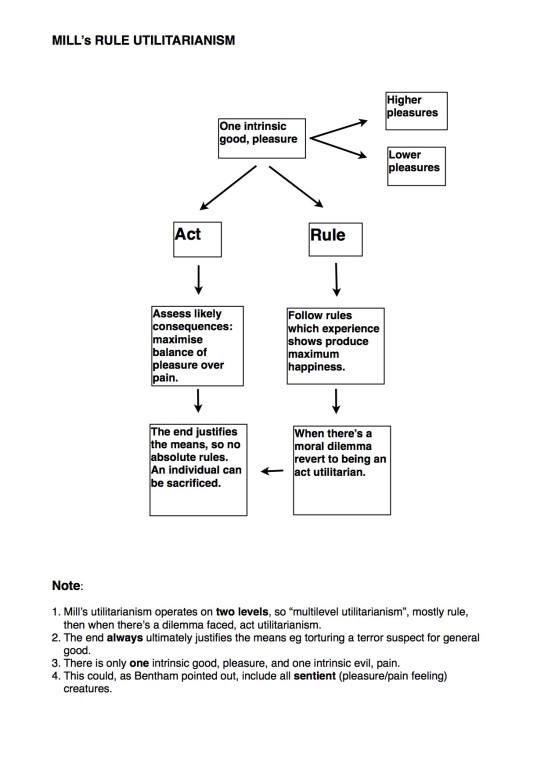

To try to eliminate some of the perceived weaknesses of act utilitarianism, Mill proposes a rule utilitarianism which argues that happiness is best maximised by following certain rules, such as the rule that you are innocent before proved guilty.

One strategy that utilitarians, including Mill, have adopted to try to avoid these arguments about the injustice of the outcome,  is to argue for rule utilitarianism. Rule utilitarianism holds that an act is right if it conforms with a set of rules the adoption of which produces the happiest outcome.

is to argue for rule utilitarianism. Rule utilitarianism holds that an act is right if it conforms with a set of rules the adoption of which produces the happiest outcome.

Mill takes trouble to argue in the last section of his essay Utilitarianism that unhappiness is caused by selfishness, by people “acting only for themselves”, and that for a person to be happy they need “to cultivate a fellow feeling with the collective interests of mankind” (p145) and “in the golden rule of Jesus we find the whole ethics of utility” (p148). We might add that the Situation Ethicist Joseph Fletcher claims Jesus as his own, as does Immanuel Kant who argued that Matthew 7:23 “do to others as you would have them do to you” was very close to his first formulation of the categorical imperative, that of universalisability.

Perhaps Mill recognized that utilitarian philosophy contradicted the argument in his, in my view, much greater essay On Liberty, where he argues that the only justification for infringing personal liberty is to prevent harm to others. So the utilitarian argument for locking up thousands of Japanese Americans during the second world war, that some of them might be spies, would have no justification according to Mill’s On Liberty.

In Utilitarianism Mill defends the concept of rights in terms of utility:

“To have a right, then, is, I conceive, to have something which society should defend me in possession of. If the objector asks why? I can give no other answer than general utility.” J.S.Mill

So Mill appears to be arguing here that general happiness requires that some rights be guaranteed, such as the rights to life, liberty, and property. So the rules become: life is sacred and can never be taken away, freedom is a right which can only be infringed under particular circumstances, and property is defended by rules of access and entitlement.

Yet a little later in the essay, Mill appears to argue that these rights can be infringed for the greater good.

“Justice is a name for certain moral requirements, which, regarded collectively, stand higher in the scale of social utility, and are therefore of more paramount obligation, than any others: though particular cases may occur in which some other social duty is so important as to overrule any one of the general maxims of justice. Thus to save a life it may not only be allowable, but a duty, to steal, or take by force, the necessary food or medicine, or to kidnap, or compel to officiate, the only qualified medical practitioner”. J.S.Mill

Mill goes on to stress the importance of rules underpinning the idea of justice, which he has attempted to show are grounded on the greatest happiness principle. These rules, he says, have a “more absolute obligation”, implying that in cases of conflicting claims to right action (such as occurred for Jim with the indians) the rules of justice and implicit rights to life, liberty and property must take precedence.

“I account the justice which is grounded on utility to be the chief part, and incomparably the most sacred and binding part, of all morality. Justice is a name for certain classes of moral rules, which concern the essentials of human well-being more nearly, and are therefore of more absolute obligation, than any other rules for the guidance of life.” J.S.Mill

No wonder Macintyre calls Mill “an inconsistent utilitarian” and Vardy, in a lecture in 2006, suggested that the question whether Mill was an act or rule utilitarian was far from clear. On the following page I summarise the major differences between Bentham and Mill. because of his emphasis on rules which promote social happiness, Mill is described as a weak Rule Utilitarian. We might also describe him as amultilevel utilitarian:

Level 1: Generally keep rules that promote social happiness.

Level 2: Become an act utilitarian if, in a particular situation, there is a strong utilitarian case for so doing.

| Bentham (1748-1832) | Mill (1806-1873) |

| Empirical (measure goodness a posteriori)Hedonistic (pleasure based)Consequentialist

Act utilitarian |

Empirical (against the intuitionists)Eudaimonistic (happiness based)Consequentialist

Rule utilitarian |

| Intrinsic good – pleasure Two sovereign masters – pain and pleasure. One intrinsic good – happiness. | Intrinsic good – happiness Happiness was more than just pleasure, but about having goals and virtues as well as pleasure. |

| Act utilitarianHappiness is maximised by actions that produce the maximum amount of pleasure, and minimum pain, for the greatest number of people. | Rule utilitarianHappiness is maximised by following social rules, beliefs and practices which past experience have shown create happiness. |

| Quantitative pleasure Pleasure could be calculated by the Hedonic calculus(acronym P.R.R.I.C.E.D.) | Qualitative pleasure Pleasure needs to be defined carefully to avoid creating a “swinish philosophy” – so Mill distinguishes between higher pleasures (music, art, poetry) and lower pleasures (food, drink, sex). Higher pleasures are more valuable. |

| Goodness as pleasure What makes an action good is the balance of pleasure over pain for the maximum number of people. Bentham is a psychological hedonist – pleasure is our motivation (not duty, God, or loyalties). | Goodness as happiness What makes an action good is the balance of happiness over unhappiness which it produces, where happiness is close to Aristotle’s idea of eudaimonia (includes goals, expectations, and character). |

| Justice ignored Bentham doesn’t address the issue of the rights of the minority which may be infringed by maximising pleasure of the majority (eg lynchings). | Justice addressed Mill was concerned about rights and justice and argued that happiness could only be maximised by having certain rights guaranteed and laws or rules which promoted general happiness. |

| Motivation – self-interest Bentham saw utility in narrow, individualistic terms and would agree with Margaret Thatcher’s saying– “there is no thing as society, just individuals”. He was suspicious of sympathy/antipathy as internal guides to action as they often conflicted with the external test of utility. | Motivation – sympathy Mill argued that we have a general sympathy for other human beings which gave us the motivation to seek the general good, not just our own. |

| Single level – AU Bentham’s theory operates only on the level of individual choice and pleasure applied to action. Such action can be influenced by laws and taboos – but remains an individual choice. | Multilevel – weak RU Level 1: follow rules experience has shown create happinessLevel 2: where a strong utilitarian reason exists, break the rule in this circumstance. |

| Criticisms of Bentham Assumes pleasure is the only good (what of duty, sacrifice etc?).

Assumes pleasure and happiness are identical (they’re not – think of an athlete in training).

Believes we can calculate pleasure empirically (we can’t).

Ignores problems of injustices which utilitarianism produces (see Bernard Williams’ critique). |

Criticisms of Mill Assumes happiness is the only good (what of virtue?).

Assumes higher pleasures are more desired than lower pleasures.

Makes the difficulty of calculation even more problematic by this higher/lower distinction.

Rule utilitarianism collapses into act utilitarianism when we face moral dilemmas. |

Click here if you need some further guidelines on evaluating the difference between Bentham and Mill.

Duty versus Pleasure

Ross argued for a deontological (duty-based) form of intuitionism. At least Ross’ theory allows us a way out when two rules conflict (do I lie to save a friend?). By ranking duties we can argue that one duty is more important than another(saving a life is more important than not lying).

In daily life we often feel the clash between duty and pleasure. In the morning I would prefer to lie in bed than walk the dog on a cold day; in the evening you would rather watch Hollyoaks than finish your ethics essay. Mill suggested in the quote above that we sometimes have a duty to steal in order to save a life, perhaps hinting that there is some kind of moral hierarchy. At the top, we place preservation of life, and lower down, the rule “thou shalt not steal”.

W.D. Ross (1877-1971) suggests we have prima facie (arising at first sight) duties. I may have a prima facie duty to keep my promise to meet you for coffee today, but if my child is injured in a car accident my duty is to be by his side, even if this means missing my coffee appointment. I may have promised to meet you, but I can break that promise if a more pressing obligation appears, such as helping my child recover. In cases of conflict, I make a decision based on intuition to ignore my prima facie duty. My duty to help my child ( one prima facie duty) overrides my duty to keep my promise (another prima facie duty) in the above example.

Ross argues that utilitarianism “seems to simplify unduly our relations to our fellows“.

“It says, in effect, that the only significant relation in which my neighbours stand to me is that of being possible beneficiaries by my action. They do stand in this relation to me, and this relation is morally significant. But they may also stand to me in the relation of promisee to promiser, or creditor to debtor, of wife to husband, of child to parent, of friend to friend, of fellow-countryman to fellow-countryman, and the like; and each of these relations is the foundation of a prima-facie duty.” W.D.Ross

Putting these two features together, we can say that utilitarianism is unable to explain what promising is. A promise is a way of creating a commitment, of putting yourself under an obligation to someone.

Similarly a utilitarian cannot explain what faithfulness is, what a debt is, what gratitude is, what desert is.

Ross gives a list of things he considers prima facie obligations: keeping a promise, returning a favour, promoting the good of others. These obligations are intuitively certain and are of a general sort, and according to Ross, we remain certain that they are obligations even when, in extreme circumstances such as I mentioned above, we are compelled to break them.

“The moral order expressed in these propositions is just as much part of the fundamental nature of the universe…as the spatial structure expressed in geometry” (W.D.Ross, 1930:29)

Ross therefore gives us a way out of moral dilemmas, and we might call this a multilevel approach. Level 1 is “follow the prima facie duty” and level 2 is “make a judgement when two duties conflict”. His is a deontological approach, but if you followed the above argument, Ross is not an absolutist, as you can break a promise in some circumstances.

Ross was also an intuitionist who argued for moral feelings which were innate to all of us. This brief discussion of his views reminds us again that there are three basic ways of establishing the “good”: by consequences, rules and feelings (see the introduction to ethics handout).

Strengths and weaknesses of Utilitarianism

Strengths

- Simplicity, as it gives a clear basis for making policy decisions and is still instrumental in framing laws on ethical issues, such as the Abortion Act 1967 and the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008.

- Equality, as “everyone to count as one, and no-one as more than one” (Bentham). The happiness of the individual is of equal weight irrespective of wealth, status or education.

- Benevolence, as it seeks to promote concern for the happiness of others and the happiness of society generally, which as Mill pointed out, is selfless moral stance. Mill argues that utilitarianism is based on a “general sympathy” we have for one another (sympathy is, of course, a moral virtue).

Weaknesses

- Lack of integrity: it suffers, as Bernard Williams points out, from being an instrumental, means to an end philosophy, which fails to take into account moral character and the importance of integrity (being true to one’s own beliefs).

- Injustice: it suffers from the possibility of immoral outcomes, where a person or groups of people(Jews or negroes) become scapegoats for the happiness of the majority. So moral fanatics such as Stalin or Hitler or the lynch mob in the southern states could claim they were acting to maximize happiness.

- Calculation problems: utilitarianism requires constant calculations, but who do we include, and how do we know exactly what the outcomes of our action will be?

Lawrence Hinman of the University of San Diego concludes that:

“Utilitarianism is most appropriate for policy decisions, as long as a strong notion of fundamental human rights guarantees that it will not violate the rights of small minorities“. Lawrence Hinman

Maybe it was this sort of conclusion which Mill was groping towards when he wrote his seemingly contradictory essays On Liberty and Utilitarianism.

Peter Baron October 2008, revised 2015

Level 1 reading (PMB)

J.S. Mill Utilitarianism (Project Guttenburg, on this site and used with permission)

J.C.C. Smart and Bernard Williams (1985) Utilitarianism: For and Against (Cambridge: cambridge University Press)

W.D. Ross (1930) The Right and the Good (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Peter Singer (1993) Practical Ethics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Martha Nussbaum Mill Between Aristotle and Bentham

http://www.utilitarian.net/jsmill/about/20040322.htm

Bentham’s philosophy from the journal Utilisme is discussed by Didier Hagbe:

http://didierhagbe.canalblog.com/archives/jeremy_bentham/index.html

A full list of articles based around Bernard Williams’ obejctions to utilitarianism, are found here:

http://www.philosophy.utah.edu/Faculty/millgram/wms/wmsrdngs.html

Level 2 reading consequentialism (Bristol University website)

Consequentialism is a theory which has its origins in Hume, but was subsequently developed as a distinctive theory by Bentham and Mill. It defines the right in terms of the good impartially conceived, most commonly in terms of maximising the good. Consequentialists have offered different accounts of the good: pleasure (hedonism), desire-satisfaction, or an objective-list account. Act-consequentialists insist that the right act is that which maximises the good, while rule-consequentialists insist that the right act is that which conforms to a rule which maximises the good. Consequentialism has been the object of numerous criticisms, such as: the theory cannot account for justice and rights (i.e., fails to accommodate agent-centred restrictions); it is too demanding (i.e., it fails to accommodate agent-centred options); it violates the integrity of agents; and it gives a skewed account of moral reasoning and human psychology. More recently many consequentialists have sought to develop indirect consequentialism in an attempt to deal with many of these problems.

Glover, J. (ed.), Utilitarianism and its Critics

Kagan, S. The Limits of Morality

Lyons, D. Forms and Limits of Utilitarianism

Mill, J.S. Utilitarianism

Parfit, D. Reasons and Persons

Scheffler, S. (ed.), Consequentialism and its Critics

Scheffler, S. The Rejection of Consequentialism

Sen, A. and B. Williams (eds.), Utilitarianism and Beyond

Slote, M. Common Sense Morality and Consequentialism

Smart, J.C.C. and B. Williams, Utilitarianism: For and Against

One abuse of the principle of equality was the patronage system operated by the Whig party which ensured that a very few people controlled the majority of the House of Commons’ seats. Leslie Stephen comments:

Meanwhile the Whigs were conveniently blind to another side of the question. If the king could buy, it was because there were plenty of people both able and willing to sell. Bubb Dodington, a typical example of the old system, had five or six seats at his disposal: subject only to the necessity of throwing a few pounds to the ‘venal wretches’ who went through the form of voting, and by dealing in what he calls this ‘merchantable ware’ he managed by lifelong efforts to wriggle into a peerage. The Dodingtons, that is, sold because they bought. The ‘venal wretches’ were the lucky franchise-holders in rotten boroughs. The ‘Friends of the People'(2*) in 1793 made the often-repeated statement that 154 individuals returned 307 members, that is, a majority of the house. In Cornwall, again, 21 boroughs with 453 electors controlled by about 15 individuals returned 42 members,(3*) or, with the two county members, only one member less than Scotland; and the Scottish members were elected by close corporations in boroughs and by the great families in counties. No wonder if the House of Commons seemed at times to be little more than an exchange for the traffic between the proprietors of votes and the proprietors of offices and pensions.

http://www.efm.bris.ac.uk/het/bentham/stephen1.htm

Bentham supported animal rights and equality for all irrespective of colour or creed.

The day has been, I am sad to say in many places it is not yet past, in which the greater part of the species, under the denomination of slaves, have been treated by the law exactly upon the same footing, as, in England for example, the inferior races of animals are still. The day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been witholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may one day come to be recognised that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog, is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month, old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? (Bentham, Jeremy.Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, second edition, 1823, chapter 17, footnote.)

0 Comments