Handout: Money and Banking

14th September 2015

Money and Banking

In the previous handout we discussed how banks operate and how money is created. Most of us use banks as a place to keep our money safe, to borrow more money, and to facilitate transactions with other people through checks and debit cards. But what do banks do when they need a place to keep their cash safe, or need a source to borrow from, or want someone to help facilitate transactions? Historically commercial banks have often used other commercial banks for these needs. But as banking evolved and expanded in the 19th and early 20th centuries showed that banks needed something more. With a disturbing frequency, banking crises would develop where banks were either afraid to lend to each other or they failed in large numbers. When the banks failed, innocent regular deposit customers lost money. As these “banking panics” would spread, business loans became hard to get forcing otherwise healthy businesses and industries to curtail production and lay off workers. Depressions ensued. What was needed was a combination of both regulation of banks so that they didn’t take excessive risks and a bank that could and would always lend to the banks themselves, even in crisis times. They needed a banker’s bank.They needed a bank that has commercial banks for customers. They needed what we now call a central bank.

Here we consider central banking. In the U.S. the central bank is The Federal Reserve System, in the UK, the Bank of England. The Federal Reserve System is usually referred to by economists, bankers, and businesspeople as simply The Fed, even though The Fed is not really a part of the U.S. federal government. There’s a close relationship between them, but legally The Fed (The Federal Reserve Bank) is independent of the federal government. In this unit, then, our objective is to: Describe and define the functions and policy tools of The Federal Reserve System.

Textbooks provide a very lightweight discussion of The Federal Reserve System. Therefore, it’s worth researching carefully the role of the central bank, be it the Fed or the Bank of England.

Why We Need Central Banks (or something like them)

In the last handout we discussed how banks operate and how money is created. The invention and evolution of money is  one of the most important (and powerful) developments in all economic history. Money enables trade and specialization, which raise living standards. But the existence of money creates new problems, such as safe-keeping it and borrowing. Banks evolved over the past several hundred years as a solution to these problems. The growth of banking was most dramatic in the 18th and 19th century. But while banks solve some economic problems for customers, the banks themselves can run into problems. The greatest problem a fractional-reserve bank can encounter is a bank run. If deposit customers panic and attempt to withdraw an unexpectedly large amount of funds suddenly, the bank won’t have enough cash reserves to make good on the withdrawal requests. The bank will fail. When banks fail, the remaining depositors lose their deposits completely. [note: modern depositors are insured against bank failure by FDIC to protect deposits up to $100,000].

one of the most important (and powerful) developments in all economic history. Money enables trade and specialization, which raise living standards. But the existence of money creates new problems, such as safe-keeping it and borrowing. Banks evolved over the past several hundred years as a solution to these problems. The growth of banking was most dramatic in the 18th and 19th century. But while banks solve some economic problems for customers, the banks themselves can run into problems. The greatest problem a fractional-reserve bank can encounter is a bank run. If deposit customers panic and attempt to withdraw an unexpectedly large amount of funds suddenly, the bank won’t have enough cash reserves to make good on the withdrawal requests. The bank will fail. When banks fail, the remaining depositors lose their deposits completely. [note: modern depositors are insured against bank failure by FDIC to protect deposits up to $100,000].

Bank runs aren’t the only problem banks face. Another more basic problem is “what to use for money?” Historically, gold, silver, and government-issued coins were the most common monies. But metals are cumbersome and difficult to use. So eventually people began trading and using the paper receipts they got when they made a deposit at the bank. These receipts were quite fancy (to prevent counterfeiting) and issued by the bank itself. These paper receipts, properly called bank notes, were the original paper money. They were actually receipts that could be taken to the issuing bank and redeemed for gold, silver, or coins. For example, consider this image of a $5 dollar bill likely to be seen in Michigan in the early 1900’s:

At first glance, it looks like any ordinary $5 dollar bill. It has Abraham LIncoln on the front and the Lincoln Memorial on the back. It’s green. But look closer. It says that the “First National Bank of Sault Ste Marie will pay to the bearer five dollars” and it’s labeled “National Currency” at the top. The bank issued this note itself a common early practice.(for more examples see: http://www.banknotes.com/us.htm)

Historically, paper money proved quite popular. After all, who wants to carry all that gold or coins around when you can use a few scraps of paper. Eventually each commercial bank issued it’s own bank notes or paper money. This brought a new problem since not everybody would accept just any bank’s notes. Eventually governments moved to control the issuance of paper money. What we call currency was born.

Government control or standardization of the issuance of paper money created new problems. In particular, a problem of controlling the quantity of money arose. The problem was how to ensure that banks actually had enough reserves (cash) on-hand to pay withdrawal demands and to make sure that the quantity of money wasn’t growing too fast or too slow. After a series of banking panics in the 19th centuries, most nations moved to create central banks. The U.S. twice attempted to create a permanent central bank between 1788 and 1836. However, after that Congress banned having a central bank. In 1909 we had another of the increasingly frequent banking panics, except this one threatened to take down all of the large New York city and Wall Street banks. Following this crisis, Congress created The Federal Reserve System in 1913, our version of a central bank.

Central banks solve a wide range of problems. They can regulate the creation of the new money that banks create when they make loans. They regulate commercial banks to ensure banks are solvent, have adequate reserves,and are not taking excessive risks. They facilitate transactions between different banks and help to clear checks. They provide a mechanism to exchange one nation’s currency into another nation’s currency (foreign exchange), which facilitates international trade. They replace worn-out and used coins and currency (ever wonder what happened to that dollar bill you tore and taped together?). Central banks are useful, particularly to commercial banks. Central banks also have the potential to be useful to the nation and the larger economy through monetary policy, if the leaders of the central bank choose to do so.

Because central banks have the powers to provide these services, they also have enormous economic power and  influence. In short, central banks can influence the money supply, the general level of interest rates (especially short-term rates and rates on government bonds), and how fast commercial banks create new money in an economy. Through interest rates, they usually have enormous influence on how much investment spending happens in the economy and how much consumer spending occurs, meaning the can influence real GDP. Although the central bank doesn’t directly set most interest rates, their decisions on the one interest they can set (discount rate), they can strongly influence all other rates either up or down. This means central banks have enormous power to influence (not control) the growth of GDP.

influence. In short, central banks can influence the money supply, the general level of interest rates (especially short-term rates and rates on government bonds), and how fast commercial banks create new money in an economy. Through interest rates, they usually have enormous influence on how much investment spending happens in the economy and how much consumer spending occurs, meaning the can influence real GDP. Although the central bank doesn’t directly set most interest rates, their decisions on the one interest they can set (discount rate), they can strongly influence all other rates either up or down. This means central banks have enormous power to influence (not control) the growth of GDP.

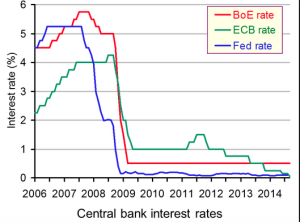

In today’s modern economies central bank monetary policies are at least as important, if not more important, than government fiscal policies in determining whether we achieve our macroeconomic goals. In the period since the late 1970’s when pure Keynesian fiscal policy began to fall out of favour with policy-makers, central banks assumed even greater importance. In most of the industrialised, developed economies of the world, it has been central banks (The Fed, Bank of England, EuroBank, Bank of Japan, etc) that have done most of the “heavy lifting” in managing policy to achieve macroeconomics goals, with Keynesian fiscal policy often being considered as a second-option in case monetary policy failed such as it did in 2008-09,

You should read the Wikipedia article on Central Banks now (another copy of this link is listed with the Reading Guide).

The Federal Reserve System and the Bank of England

The Federal Reserve System is an extremely powerful institution. The comments of just one member of the Board of Governors can cause traders and investors on the stock exchanges to push stock prices up or down the same day. And that’s just when The Fed talks. When The Fed acts, markets and the entire economy respond. Our aim in this unit and the next unit is to understand how and why The Fed is so important and how it affects the economy. Right now your focus should be on how The Fed is organised and what it’s powers are. In the next unit we will explore how The Fed’s actions affect the economy through what’s called monetary policy. Now would be good time to read the Wikipedia article on The Federal Reserve System (another copy of this link is listed with the Reading Guide) and the text book readings.

The Fed, the Money Supply, and Banks: Creating New Money By Making Loans

Understanding the process by which banks create more money (add to M1) is absolutely essential. I will not discuss it here, though. You should pay very close attention to your textbook about this process. As you understand the process by which banks determine their required and excess reserves, and then are able to loan out the excess reserves, you will gain an insight into how powerful The Fed is. You will also learn what The Fed’s major powers, as with the Bank of England in the UK, are:

- setting required reserve ratio

- setting discount rate for loans to banks

- open market operations (such as quantitative easing QE)

- foreign exchange operations

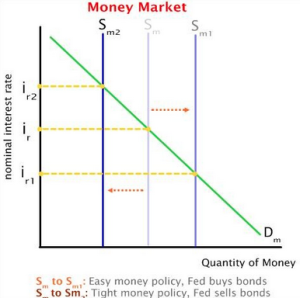

Of these powers, the most important is open market operations. One way the central bank does this is by altering the supply of money by buying or selling gilt-edged stock. If the Fed or Bank of England buys gilts, this increases the amount banks can lend and leads to a shift outwards in the supply of money (diagram below). Ceteris paribus, lower interest rates result. The ability of central bank to set the required reserve  ratio is probably the most obvious way that The Fed can control how banks create new money. However, The Fed rarely uses this policy. Changes in required reserve ratios may only happen a couple times during the course of an entire recession-expansion cycle. In the most recent cycles, required reserve ratios have been left untouched as The Fed prefers to use other tools. It’s interesting that in some countries such as Canada and Australia, there is no precise required reserve ratios. Banks in those countries are simply legally required to always have “enough reserves”.

ratio is probably the most obvious way that The Fed can control how banks create new money. However, The Fed rarely uses this policy. Changes in required reserve ratios may only happen a couple times during the course of an entire recession-expansion cycle. In the most recent cycles, required reserve ratios have been left untouched as The Fed prefers to use other tools. It’s interesting that in some countries such as Canada and Australia, there is no precise required reserve ratios. Banks in those countries are simply legally required to always have “enough reserves”.

The most notorious power of The Fed is the ability to set the discount rate on loans it makes to banks. Commercial banks, when they want or need more reserves immediately, will borrow (issue securities or re-po agreements) from either other banks or from The Fed. If they borrow from other U.S. banks, they are borrowing in a competitive market and get charged an interest rate called “fed funds rate”. In the United Kingdom, the interest rate charged on these kinds of inter-bank loans is called the LIBOR (London Interbank Rate). If, however, a bank borrows more reserves from The Fed itself instead of another commercial bank, it pays an interest rate called the “discount rate”. The discount rate is arbitrarily set by The Fed as part of its policy mix. Typically changes in the discount rate are tied to Fed announcements of changes in it’s target for the Fed Funds rate.

The Fed doesn’t directly control the Fed Funds rate. The Fed Funds rate is determined by supply and demand of funds between banks. But since The Fed can supply more funds (reserves) to banks, it can influence the Fed Funds rate. Changes in the Discount Rate and in The Fed’s targets for what it thinks Fed Funds rate should be get the most publicity in the popular media. But economically, changes in these two interest rates aren’t the most significant powers of The Fed. They mostly get the publicity they do because they are easy to understand, make good media sound bites, and they provide a clue as to what The Fed is currently thinking. For a clearer definition of what Fed Funds are, see this short Wikipedia article.

The Fed cannot directly “set” or “determine” interest rates such as the prime rate, mortgage rates, auto loan rates or credit card rates. The Fed has some influence over these rates since The Fed does set or limit the rates banks pay on loans that the banks take. Obviously, if a bank borrows from The Fed at 4% and then loans that money out to the bank’s customers in the form of a mortgage or auto loan, the bank will want to charge a rate higher than the 4% The Fed charged the bank. But if The Fed lowers that rate, there is no reason other than competition from other banks why the bank would lower it’s mortgage or auto loan rates. No matter how many news reporters or mortgage company spokespeople say that “The Fed lowered (or raised) mortgage rates”, it simply isn’t true.

The most powerful tool The Fed has is open market operations. The Fed uses this tool on a daily basis. Everyday The Fed will enter the public bond market to either buy or sell government bonds from commercial banks. If commercial banks have a lot of reserves on hand, the banks can make a lot of loans and create a lot of new money. If The Fed thinks commercial banks have too much reserves on hand, it will make very attractive offers to sell bonds and securities to those banks. The banks pay for these securities and bonds with cash – their reserves. Thus The Fed can sell bonds and reduce bank reserves, which reduces the ability to create M1. The reverse is also true. If The Fed wants banks to make more loans and create more M1, it can provide an increase in reserves to the banks. The Fed will make very attractive offers to buy bonds and securities that the commercial banks already own. These bonds and securities are actually short-term loans the bank has made to a customer. If The Fed buys these bonds and pays cash to the banks. The cash goes into bank reserves and enables the creation of new loans and new M1.

What all of these powers have in common is the ability to increase or decrease bank reserves. This ability to increase or decrease reserves in a fractional reserve banking system is what gives central banks so much power. The currency with the largest circulation in the world is the U.S. dollar. Since, The Federal Reserve System can increase or decrease the reserves of banks that loan U.S. dollars, it is one of the most powerful economic organisations on the planet.

The Money Multiplier

You should pay particular attention to the discussions in the book and elsewhere about the money multiplier. You may have encountered it in the last unit. The money multiplier is a number (a ratio actually) that tells us how much M1 will eventually be created once bank reserves are initially increased. For example, if the multiplier is 8, then that means that for every initial dollar of increase in bank reserves that The Fed creates, the eventual change in M1 will be $8. For this increase in M1 to happen, the original dollar has to be loaned out, then redeposited in a bank to create more reserves, then loaned again, then redeposited, etc. This cycling of loan-deposit-excess reserves eventually declines since each new deposit of a $1 only creates (1-RequiredReserveRatio) dollars of excess reserves. Thus the Required Reserve Ratio governs how fast new bank reserves can be multiplied into M1.

There are really two ways to calculate the money multiplier. One way, is simply: Multiplier = 1/rr, when rr is the Required Reserve Ratio. As you can see, if the Required Reserve Ratio is larger, the multiplier is smaller, and vice-versa. Calculated this way, the multiplier tells us the theoretical maximum (or ultimate) increase in M1 possible if all excess reserves get loaned out and all loans become new deposits. This is the calculation you need to keep in mind for quizzes, worksheets, and test questions.

Of course in real-life, all loans don’t become entirely new deposits. The real life multiplier is a lot lower than the theoretical multiplier we calculate from the required reserve ratio. The real life multiplier is also a lot more variable and unpredictable since it depends on banks’ own decisions. When The Fed increases bank reserves through open market operations, the new reserves don’t always or predictably increase M1 despite the theory. Most importantly, banks don’t always use the excess reserves to create new loans to customers who will spend the money. Sometimes, as in the most recent 2009-2012 period, large banks have used their excess reserves to speculate on commodities or derivatives markets, or in the case of many banks, simply refused to make new loans. To calculate the multiplier that takes into account the actual rate at which reserves are being multiplied today, it is necessary to divide total M1 by total Monetary Base. Since this method depends on actual current data, we will not use it in a quiz.

What’s Next: Monetary Policy

Money in the U.S., like that of most other countries, is no longer backed by gold or any other commodity. It is fiat money (defined as “any money declared by a government to be legal tender. State-issued money which is neither convertible by law to any other thing, nor fixed in value in terms of any objective standard. Intrinsically valueless money used as money because of government decree”). It is the creation of the UK and US banking system through loans. But The Fed or central bank has enormous influence through its ability to manage the discount rate, influence Fed funds rates, and open market operations whereby the central bank buys and sells government gilt-edged stock (also known as government debt). In the next handout we study how these powers come together to form monetary policy and influence the wider economy, including real variables such as GDP growth, investment and the level of exports.

0 Comments