Handout: International Trade and Exchange Rates

14th September 2015

Building from the Core Concept: From The Circular Flow to a Theory of Exchange Rates

We have so far built a basic model of how a macroeconomy works: the circular flow model and it’s measures of performance. We have also examined two theories about how government, firm, and household decisions about spending and production affect the real economy while making some simplistic assumptions about the financial markets. We then added money to the mix. Specifically, we studied the financial sector and how central banks, in particular, can affect our macroeconomic performance.

Our studies so far have left out one very important piece of the macroeconomy: the rest-of-the-world (ROW). So far we have focused on government, domestic firms, domestic households, banks, and the central bank. In short, we have studied what economists call a closed economy. But all economies are subject to globalisation, the trend towards increased international trade and capital flows. We will begin the last part of this course, Part IV, by examining the relationship between the macroeconomy and the rest of the world, focusing on accounting for the money flows and looking at the effects of exchange rates.

There’s more to open economy issues, but our focus has tended to be on the U.S. or the UK. The U.S. is less affected by these interactions with ROW than most nations (such as the UK which trades half its total with Europe). This is because the import/export sector of the U.S. economy is smaller relative to the total economy than most nations.

In this handout, then, our objective is to describe the process by which exchange rates are determined and the macroeconomic impact of changes in exchange rates.

Accounting for Transactions with the Rest-of-the-World

In the circular flow of goods and services, there are four types of transactions with the rest-of-the-world (ROW):

- Imports (M)

- Exports (X)

- Capital Inflows

- Capital Outflows

These transactions create flows of money as the buyers pay and the sellers receive payment. Two of these flows, Exports and Capital Inflows, represent money coming into the domestic economy from foreigners. So where did the foreigners get the money to pay for the goods (exports) they bought or to pay for the bonds, stocks, or businesses they purchased (capital inflows)? The money to pay for these two monetary in-flows comes from the other flows. The other two flows, Imports and Capital Outflows, consist of money moving from the domestic economy to foreigners to pay for foreign goods (imports) or to pay for foreign bonds, stocks, or assets purchased.

We are focusing an situations here where all of an economy’s money originates from within that economy. For example, the only source of new U.S. dollars is from either the central bank or banks in the U.S. After all, money is created by the central bank allowing banks to make loans or by the central bank printing and putting currency into circulation. We are not studying here a situation where a nation’s economy is a different, smaller entity than the origin of the money they use. In practical terms, that means we are studying the flows of money internationally that originate in nations like the U.S., U.K., Canada, Japan, Australia, Brazil, China, and others. What we are not studying is the flows of money for a nation that is part of a larger “currency union” such as the EuroZone. So what we are studying doesn’t necessarily apply in the same ways to nations like Germany, France, Greece, Italy, Ireland, etc. Those nations have the supply of money (Euros) governed by the European Central Bank – an entity outside their economy. For the UK, of course, which declined toe neter the euro in xxxx the situation s similar tot the US – the Uk controls its own currency supply of pounds.

Given that all money must originate in the domestic economy, and given that the currency is largely useless outside of the economy, this means that ultimately, the flow of money out of the economy equals the flow of money back into the economy. We call this relationship the balance of payments. This means that for any given year, the total outflows must equal the total inflows. In other words:

Capital Outflows + Imports = Capital Inflows + Exports

We can re-arrange this equation to the following (notice the minus signs):

Capital Outflows – Capital Inflows = Exports – Imports.

We have names for each side of this equation: the left hand side is called the Capital Account balance and the right hand side, the Current Account balance. It’s called ‘current’ since it involves items, goods and services, that were produced or intended to be consumed in the current time period. Capital accounts deal with items that are primarily financial assets or debts (assets – gilts, treasury bills, bank loans; debts – bank borrowing, etc).

Because the balance of payments itself is always in balance, then this means that current account balance must equal capital account balance. So, let’s suppose a nation is running deficit in its current account. This means that “exports – imports” is a negative, much like the U.S. has done for nearly 4 decades. In other words, imports are greater than exports. So, on balance, money is leaving the country with a current account deficit. The money must find it’s way back to the economy. If foreigners are not buying our exports with the money they earn from selling us imports, then they must return the money in the form of capital inflows. See the tutorial for more detail.

What’s in the Flows?

Exports and imports are relatively easily understood items. We’re all familiar with foreign-made products that we’ve purchased. For example, when an American buys a Japanese-built car or a Chinese-made toy, that’s an import. When people in other countries buy copies of Microsoft Windows, Boeing airliners, or corn grown in Iowa, they are buying our exports. (find out what the top ten exporting industries in the U.S. are here).

But the current account includes more than just goods like these. There is a large and lively international trade in services, also. There are also significant payments for things like copyright or patent royalties which are called income receipts. Finally, there are also transactions called unilateral transfers. Unilateral transfers are essentially international gifts. A person or entity in one nation simply sends money to somebody else in another nation. Sometimes these unilateral transfers are organised charity (remember those TV commercials urging you to donate to support a famine vicitm?), or they are government grant programmes. Most often unilateral transfers are monies sent “home” by recent immigrant workers.

Capital flows are a bit more complex. The biggest volume of international capital flows are simply bank deposits and government bonds. When someone in Japan purchases a new UK government bond (sometimes called gilts), they are loaning money to the UK. government – it is a capital inflow. If some foreigner, suppose an extremely rich person, wishes to keep their financial wealth safe, they may well choose to keep it on deposit with a UK bank. When they make that deposit, it’s a capital inflow to the UK. Capital flows can also take the form of “foreign direct investment”, for FDI. FDI is when a foreigner buys or builds a business in another country. For example, when Nissan, a Japanese company, builds a factory in the Sunderland, UK, it’s FDI, a capital inflow. When General Motors, a U.S. company, builds a factory or invests in a partnership with a Chinese car maker, it’s FDI, a capital outflow from the U.S. When foreign central banks increase their holdings of U.S. or UK currency, it is also considered a capital inflow into the U.S or into the UK.

What Causes Capital or Current Account Deficits/Surpluses?

A deficit in the current account will be matched by a surplus in the capital account, and vice-versa. So which one “causes” the other? Does the U.S. receive a surplus capital inflow because it chooses to buy more imports than exports? Or do we buy end up running a current account deficit (buy more imports) because we attract so much capital from overseas? Economists disagree. The reality is probably best described as the two are simultaneously determined. Current and capital account balances are driven partly by real economic factors: comparative advantage in producing goods, real productivity and resources available for production, and the opportunities for investment and growth. But there are also other significant short-term factors: interest rates, inflation, government budget deficits, national savings rates, currency exchange rates, and fear of economic/political uncertainty worldwide.

Currencies and Foreign Exchange Rates

Each nation creates and manages it’s own currency — its money (except for those who have joined a currency union like the Eurozone). The Federal Reserve System is ultimately responsible for how much U.S. money is available and circulating in the economy. With the UK the Bank of England performs the same role. Within an economy, this money is adequate for all transactions. Buyers pay with it and sellers accept it. But when we introduce international trade, we also introduce a difference in monies and the possibility that people will want to buy one currency with units of another currency (convert currency).

Let’s suppose an American and a German decide to trade. To be specific, the American wants to buy a car from Mercedes-Benz of Germany. The American has US dollars available to spend. But Daimler, the German company that makes the Mercedes, ultimately needs Euros, not dollars (they use the Euro in Germany). Daimler pays it’s suppliers in Euros. It pays it’s employees in Euros. And it wants it’s profits in Euros. The solution is to sell the car to the American and accept payment in US dollars. Then Daimler takes the US dollars and converts it to Euros in the international currency markets.

This “currency conversion” is done in a market for currency called the foreign exchange markets, often called “forex” for short. In the foreign exchange markets, Daimler wants to “sell” the US dollars it now possesses to someone in return for Euros. It needs someone who has Euros that they want to use to buy dollars. Once this foreign exchange transaction is made, then Daimler will have the Euros it originally wanted and it can pay it’s suppliers, employees, and shareholders. The rate at which the US dollars were traded for Euros is called the foreign exchange rate, or currency conversion rate. The tutorial has a section on reading tables of foreign exchange rates.

Why Foreign Exchange Rates Are Important

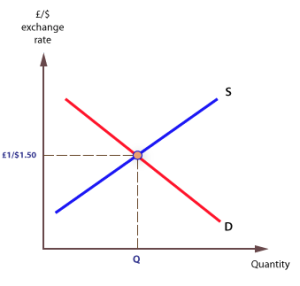

The rate at which two currencies exchange is of critical importance in determining international trade patterns, and tehre is a demand and supply curve for currency just as if it was a product (see diagram below). Let’s  suppose a British manufacturer is selling their product in Britain for £55. At £52 , the firm makes a reasonable profit and can afford to do the business. Now they look at possibly exporting the product to the U.S. In the U.S., let’s suppose that a competitive U.S.-made product is selling for $100 USD. Can the British manufacturer afford to export to the U.S. and compete at the $100 U.S. price? Will U.S. customers be willing pay enough for the British product? The answer depends on the exchange rate. Suppose the exchange rate is $1USD will trade for £0.50 . At this exchange rate, the British company could sell at the “market price” in the U.S. and receive $100 for each unit they sell.

suppose a British manufacturer is selling their product in Britain for £55. At £52 , the firm makes a reasonable profit and can afford to do the business. Now they look at possibly exporting the product to the U.S. In the U.S., let’s suppose that a competitive U.S.-made product is selling for $100 USD. Can the British manufacturer afford to export to the U.S. and compete at the $100 U.S. price? Will U.S. customers be willing pay enough for the British product? The answer depends on the exchange rate. Suppose the exchange rate is $1USD will trade for £0.50 . At this exchange rate, the British company could sell at the “market price” in the U.S. and receive $100 for each unit they sell.

Then they convert the US dollars into Pounds in the foreign exchange markets. At the $1.00USD = £0.50 exchange rate, the $100 US dollars becomes £50 . It’s not enough for company to make a profit. But suppose, the exchange rate changed to $1.00USD = £0.55 . At the new exchange rate, the US market price of $100 gets converted into £55 . Not only would the British firm be able to sell in the U.S. at this exchange rate, they would actually make more profit on their US sales than they would on British sales. Of course, instead of making “extra” profit on their U.S. sales, at the $1.00USD = £0.55 exchange rate, the British firm could price their product at the $94.55 US dollars in the U.S. At this price the British firm would convert the $94.55 USD into £52 , the amount they were looking for, but they would also undercut the price of their U.S.-based competitors. As you can see, the volume of imports and exports a country has can easily be affected by the exchange rates between currencies.

The same holds true for consumers. Suppose you have $3000 USD to spend on a vacation (assuming you are in the US). Where will your money go the farthest? It depends on exchange rates. Let’s suppose that you researched and figured out that $3000 would buy you a decent vacation in Paris next summer (France, not Kentucky!). You save your money all year-long and when summer arrives, you’ve saved up your $3000. But suppose the interim while you were saving up for the vacation, the US dollar weakened. This means that the exchange rate of US dollars into Euros changed so that each US dollar buys fewer Euros and it takes more dollars to buy each Euro. Your $3000 won’t buy you the vacation in Paris. On the other hand, someone in France may well have found that the vacation to Disney World in Florida just became cheaper. International trade and capital flows depend on exchange rates.

How Are Foreign Exchange Rates Determined?

There are different ways of determining exchange rates. Each is a matter of policy and choice by the currency-officials of each nation.

One method used in the past was the gold standard. Each nation defined a fixed value of their currency in gold. Since each nation’s currency was pegged to a fixed amount of gold, the effect was to set a fixed exchange rate between currencies. The gold standard ruled international trade and currency transactions in the 19th and early 20th century. Despite the claims of some politicians today who wish a return to a gold standard, the gold standard was highly problematic from a macroeconomic perspective. A gold standard largely eliminates the ability of the central bank to manage monetary policy effectively, including interest rates. A gold standard forces a nation to tie the quantity of money in the economy, the growth of the money supply, and interest rates to the ability of a few scarce gold mines in the world to produce gold. There is no reason why the growth of gold supply will match what the economy needs or wants to maintain full employment. The history of the late 19th century and early 20th century confirms this. Today, virtually no nation has gold standard, but many currency traders still look at the price of gold bullion as an important trends indicator.

The second method is one of fixed exchange rates without using gold. Typically some particularly strong currency that is very widely used is set as the “reserve” currency. Other nations then “peg” the value of their currencies to this particular reserve currency. In the global financial system set-up after World War II at a conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in 1946, the US dollar was established as the reserve currency to which other nations would peg or fix their currency exchange rates. In a fixed system like this, the central bank of a nation must be willing to buy or sell it’s currency as necessary in order to maintain the proper exchange rate. This type of system also requires that the rest of the world have enormous confidence in the stability and value of the reserve currency.

In the post-World War II environment, the strength of the US economy and confidence in the Federal Reserve allowed the world to use the dollar as a reserve currency. To maintain such confidence, the US maintained that it would convert the US dollar into gold for foreign traders & central banks, if requested (US citizens were not allowed to convert dollars into gold). This system ended in 1972 when the US abandoned it’s commitment to convert dollars into gold. Today, there are still some nations in the world, particularly in smaller or developing nations, that continue to maintain a fixed rate to the US dollar.

In the 1970’s the world (or at least the major developed countries) attempted to move to a “floating rate regime”. In other words, exchange rates are set by market forces, supply-and-demand, in foreign exchange markets. If, on any given day the supply of dollars that people want to convert into Euros exceeds the demand for dollars by people who want to pay with Euros, then the dollar weakens — each Euro will bring a larger number of dollars and each dollar will bring fewer Euros. If the supply and demand are reversed, then the dollar strengthens and the Euro weakens.

In the long-run, a flexible market-driven system of floating exchange rates is superior – it will automatically balance out changes in economic conditions, inflations, interest rates, etc between countries. A flexible, floating exchange rate system also allows each nation to conduct the macroeconomic fiscal and monetary policies that best fit the needs of that nation. Fixed rate systems are policy “straight-jackets”. But, in the short-run a system of floating exchange rates set in open markets can be disruptive. Exchange rates can suddenly move and move dramatically, disrupting firms’ and consumer’s plans. The floating rate system is also susceptible to excessive speculation which can drive exchange rates away from what they should be in the short-run. For this reason, the real system the world uses today is called a “managed float” system. In general, exchange rates are set by market forces, but central banks often enter the market in order to slow or even reverse rate changes.

What’s A Good Exchange Rate?

Some people make a big deal about which currency has the larger number. For example, for years when the Canadian dollar was trading at a rate where 1.00 CAD would bring much less than 1.00 USD (at times as low as 1 USD = 0.67 CND), many Canadians made fun of their own money, calling it “monopoly money” or “toy currency”. In fact, the actual numbers are largely irrelevant. For instance, $1.00 US dollar buys approximately 114 Japanese yen. The 1.00 to 114 ratio itself is meaningless. It simply means the US has a currency that uses fractional amounts ( such as 25 cents, which is 0.25 dollars) in it’s economy, while Japan chooses to only use whole units of it’s currency.

The “right” exchange rate in an economic sense is the one where the same product produced from the same materials, but sold in different countries, would yield the same amount of money no matter which currency it was converted into. This is called “purchasing power parity”. But what really matters is what the actual exchange rate is, not a theoretical number. And what matters most, is changes in that rate.

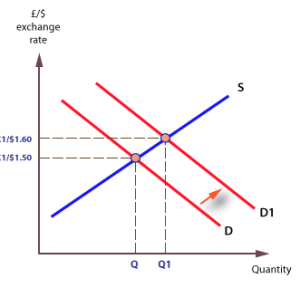

When exchange rates change, one of the currencies is described as “strengthening” or “appreciating”. The other currency  gets “weaker” or “depreciates”. A stronger currency is one which will buy more units of the other currency than it did in the past, causing the demand for that currency to shift to the right (see diagram, D1 to D2). So for example, in 2003, the US dollar would buy approximately 1.50 Canadian dollars. We can re-state this in terms of the Canadian dollar. Each Canadian dollar would buy approximately $0.66 US dollars in 2003. Since 2003, the exchange rate has changed dramatically. In the fall of 2007, four years later, the two currencies reached “parity”, meaning they traded at 1-for-1. So in Fall 2007, one US dollar would only buy 1.00 Canadian dollar. Each US dollar was now buying fewer Canadian dollars. The US dollar had weakened. Of course from the Canadian perspective, each Canadian dollar would only buy 0.67 USD in 2003, but each Canadian dollar would buy 1.00 USD in 2007. The Canadian dollar had strengthened or “risen against the dollar”.

gets “weaker” or “depreciates”. A stronger currency is one which will buy more units of the other currency than it did in the past, causing the demand for that currency to shift to the right (see diagram, D1 to D2). So for example, in 2003, the US dollar would buy approximately 1.50 Canadian dollars. We can re-state this in terms of the Canadian dollar. Each Canadian dollar would buy approximately $0.66 US dollars in 2003. Since 2003, the exchange rate has changed dramatically. In the fall of 2007, four years later, the two currencies reached “parity”, meaning they traded at 1-for-1. So in Fall 2007, one US dollar would only buy 1.00 Canadian dollar. Each US dollar was now buying fewer Canadian dollars. The US dollar had weakened. Of course from the Canadian perspective, each Canadian dollar would only buy 0.67 USD in 2003, but each Canadian dollar would buy 1.00 USD in 2007. The Canadian dollar had strengthened or “risen against the dollar”.

Winners and Losers in Exchange Rate Changes

Changes in exchange rates affect people differently, depending upon whether they are selling exports, buying imports, or travelling outside the country. In short, the following table summarizes who, in general, benefits and who is hurt by the changing value of a currency. This table is described in terms of Americans, foreigners, and the US dollar. But the same analysis holds for any currency – just substitute the other currency for dollar and replace “Americans’ with the people or firms of the nation that has the other currency.

| If Dollar Strengthens | If Dollar Weakens | |

| Will benefit (lower costs or more profits) |

|

|

| Will be hurt (higher costs or lesser profits) |

|

|

Why Exchange Rates and Balance of Payments Matters in Macroeconomics

The reason that exchange rates and the balance of payments matter is because they affect economic performance and policy-making. The current account is, in effect, the net exports part of GDP. It’s the (X-M) term in GDP = C+I+G+(X-M). When exchange rates change, it affects the level of imports and exports as you can see from seeing who “wins” and who “loses” in the above table. So changing exchange rates can affect GDP and the growth of GDP. The level of GDP of course, also affects employment. That’s three of our four macroeconomic goals right there.

The balance of payments and exchange rates also affect monetary policy too. For example, changes or unbalanced capital flows will affect the quantity of money and interest rates in the economy, thereby affecting monetary policy. In fact, that is part of what the US has been doing approximately 30 years. The US has run persistent current account deficits – meaning imports have been greater than exports. We have routinely purchased more goods from foreigners than we produce and sell to them. We have paid for these goods with US dollars. The Federal Reserve over this same time period has allowed (encouraged?) M1 to grow at faster than our growth of real GDP.

How does a U.S. current account (trade) deficit become a capital surplus?

The persistent and large U.S. current account deficit often gains a lot of attention. In particular the trade deficit with China and Japan often is targeted (we also have a very large deficit with Germany). Sometimes the corporations and banks in those nations that have a trade deficit with the U.S. send the money back directly as capital investments in the U.S. More often, though, the route back to the U.S. is more circuitous. A key is the fact that oil is priced internationally in U.S. dollars. This has been the practice for at least 4 decades. It means that any nation that needs to buy (import) oil, such as China, Germany, or Japan, must buy that oil and pay for it with U.S. dollars. The sellers of oil, such as Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Norway, Malaysia, etc, will only deliver oil in return for U.S. dollars. That means that Japan and China for example, must figure out how to get their hands on sufficient US dollars to buy oil. How can they get U.S. dollars? Sell competitively priced goods to the U.S. and get paid in dollars. Then don’t buy U.S. goods – in other words, run a trade deficit.

But what happens to the dollars? Let’s take China for example. The US gets goods and China gets dollars. They use the dollars to buy oil from Saudi Arabia. The Saudis then have the dollars. What do the Saudis do with the dollars? Invest them in U.S. bank accounts and financial investments. The money has gone full circle and the trade deficit has turned into a capital surplus for the U.S.

Final note: The pattern of oil-exporting countries accepting only US dollars has a long history, but there have been a small number of exceptions. Starting in 2001, Iraq began to sell some oil for Euros. That practice ended in April 2003 when the U.S. occupation began. Today, Venezuela accepts dollars for cash payments, but Venezuela will also negotiate barter deals with other Latin American countries. For example, it once bartered oil to Cuba in return for the services of a large number of medical doctors for a year. Finally, today, Iran has established a futures exchange for oil denominated in Euros and is widely believed to be doing deals in the last few years for other currencies. The reader is left to decide for themselves what pattern exists among these non-dollar oil sellers, because that begins to move us from economics into politics.

Jim Luke, Lansing College

0 Comments