Handout: Fat Cats, Fat Pay Packets

9th September 2015

Fat Cats, Fat Pay Packets

Increasingly the boardroom has become the focus for criticism because critics have argued that directors are motivated by self-interest. Executive pay has become the focus for public criticism and the image of the Fat Cat has become inextricably linked with the boardroom. The privatised utility companies have been accused of X-inefficiency and Organisational slack, as service providers have allowed costs to rise because of their preferred status as natural monopolies. Since these firms have few or no competitors they do not have to worry about keeping costs to a minimum and are able to exploit this position in order to increase the remuneration of senior managers through pay, share options and perks.

In 2013, the average Chief Executive earnt £4.5 m in 2013. L’Oreal adverts carry the slogan, ‘because your worth it,’ are UK Chief Eexcutives really this level of pay? To put Chief Executive pay in perspective, £4.5 m is more than 160 times the pay of the average Briton; a 5% increase on 2012.

High levels of pay for senior managers may fuel resentment amongst, workers who have experienced an extended period of low pay awards or even pay freezes.

Evidence suggests that the level of pay awards given to Chief Executives is also causing concern amongst business leaders. A poll conducted amongst members of the Institute of Directors revealed the over half of those surveyed were unhappy about rate of growth of executive pay. He consensus was that excessive pay packets for senior executives was eroding public trust in the UK’s largest companies

Curbing boardroom pay

A number of approaches could be used. One option would be to try to regulate executive pay. The difficulty with this is that rules tend to be inflexible ad individuals will try to find loopholes.

Directors do have a legal duty to act in the best interests of shareholders. If they fail to do so, then they could be sued. Legal action against Directors is a rather draconian measure and would potentially be very expensive.

AGMs have become a focus for rows over pay, with individual shareholders challenging proposed pay awards and bonus schemes. The problem with objecting to pay at AGM’s is that the share in most large companies are concentrated in the hands of a small number of large institutional investors (pension funds, banks, insurance companies and mutual funds). These large funds are often reluctant to make a stand on executive pay. Occasionally,

Prem Sikka (University of Essex) has made a radical proposal, with the suggestion that employees and customers should be given the opportunity to vote on executive remuneration.

Activist shareholders have succeeded in curbing excessive awards and few bosses do bow to public pressure. In 2014 for example, the gas company BG Group amended is proposed pay package for new chief executive Helge Lund when shareholders revolted over a proposed £12m upfront share bonus.

In another instance Ross McEwan, the boss of state-owned Royal Bank of Scotland announced in February 2015, that he would hand back £1m of a share award. This is the second time that he has chosen to forego part of his pay award. His decision reflects public concern at the large pay awards being given to executives of banks bailed out with taxpayers money during the last financial crisis.

Not all executives have been as sensitive to public pressure as Ross McEwan. Sir Martin Sorrel, head of Wire and Plastic Products Plc (despite its name he company is the largest advertising company by revenue in the world) rejected any criticism of a £36m share plan payout arguing that the cmpany’s market value had risen by £10bn over the plan’s five-year period, and the award was entirely justified

Prem Sikka, professor of accounting at the University of Essex, believes a wider group of people should have a say on pay, not just directors on “remuneration committees”. It is difficult to see how such a measure would gain support

Accelerating pay

The growth in executive pay can be traced back to the privatisation of state-owned monoplies during the 1980’s. When the companies were sold off the existing senior executive were given a significant increase in pay, even though it was the same individual doing the job. For example, Robert Evans who was Chairman of British Gas was given a pay award which was 10x the rate of inflation.

Concern about ‘fat cats’

The government commissioned the Greenbury report in 1995. The aim of the report was to produce a code of practice. The report recommended that companies should appoint a group of directors to set pay on the basis of “professional advice”. The report had two consequences:

Directors appointed to remuneration committees tended to overpay, on the principle that shareholders would not appreciate a committee who saved a few thousand pounds but in doing so prompted the resignation of an able Chief Executive who left the company because he could earn more elsewhere.

The second consequence of the Greenbury Report was that it increased the importance of the role of Pay Consultants, who tended to advise that in a global talent market, it was necessary to offer higher salaries and bonuses in order to attract the very best managers from around the world to fill the top jobs in UK.

The consequence of changes brought about by the Greenbury committee was an upward pressure on salary levels, and as one executives pay was raised in one industrial sector, then pay of bosses in similar companies tended to leapfrog over the last award set, creating a wage spiral.

Long-term incentives

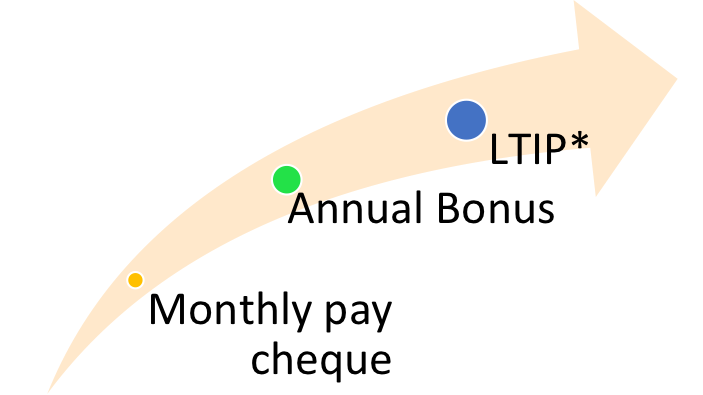

In recent years, pay awards have become more than just a process of setting salaries for senior executives. Pay awards are now made up of:

Soaring pay awards

Soaring pay awards

*LTIPs – are usually paid in cash and shares and are triggered when longer-term performance targets are met.The Soaring Level of executive pay

An LTIP is a bonus based upon long term targets (typically 3-5 years). LTIPs are often paid at least partly in shares.

The argument in favour of LTIPs is that they may focus a CEO’s mind on the long-term health of a company.

Critics argue that LTIPS may encourage managers to engage in short termism which may lead to aggressive accounting measures (window dressing) and cost cutting.

The effect of adding bonuses and LTIPs on top of basic salaries can be significant. The average bonus can double executive pay. An LTIP can increase executive pay 6x.

One of the problems of spiralling pay awards for Chief Executives is that it can also trigger wage inflation.

Premiership Footballers

Senior Executives may justify their pay awards by pointing to their short terms of office. They have more in common with Premier League Footballers than top Premier managers such as Alex Ferguson. Like Premier League footballers their time in the top flight is comparatively short. The boss of a FTSE 100 company only stays in post for an average of four years. As their time at the top is so short they need to maximise their earnings while they can. It can also be argued that salaries reflect the market value of what managers are worth, and managers like other economic goods are a scarce commodity.

‘because your worth it’

Chief Executives will use the, ‘because I am worth it’ argument to justify their pay packages. One writer on motivation commented that the only measure of their own importance that Chief Executives have is their pay packet. Chief Executives need large pay packets as a way of reflecting their importance to the company they lead and to their shareholders. In other words, the size of the pay packet is an indication of how much senior executives are ‘loved’ by the organisation.

Tasks

- Examine the role of a remuneration committee?

- Evaluate the arguments that Executive pay is justified on the grounds of ‘scarcity?’

0 Comments