EU Support is Slipping Away

30th November 2015

EU Support Slipping Away

Uk electors seem far less likely to support an enlarged EU – with migration taking centre stage as an issue.

The European Union vote, likely to be in June or September 2016, presents one of the greatest political and economic issues we have faced for some years. Evidence suggests that support for the EU is slipping away – of an average of polls from 1977, 53% supported UK membership. The highest poll rating was in In June 2015, at an all-time peak of 75%. Since then support has fallen far and fast: In November the split was 52% for and 48% against. Ian Stewart of Deloitte’s sums up the conclusions of two economists – David Bowers and Richard Mylles, on how the debate has shifted since the referendum of 1975, when 67.2% of voters supported membership.

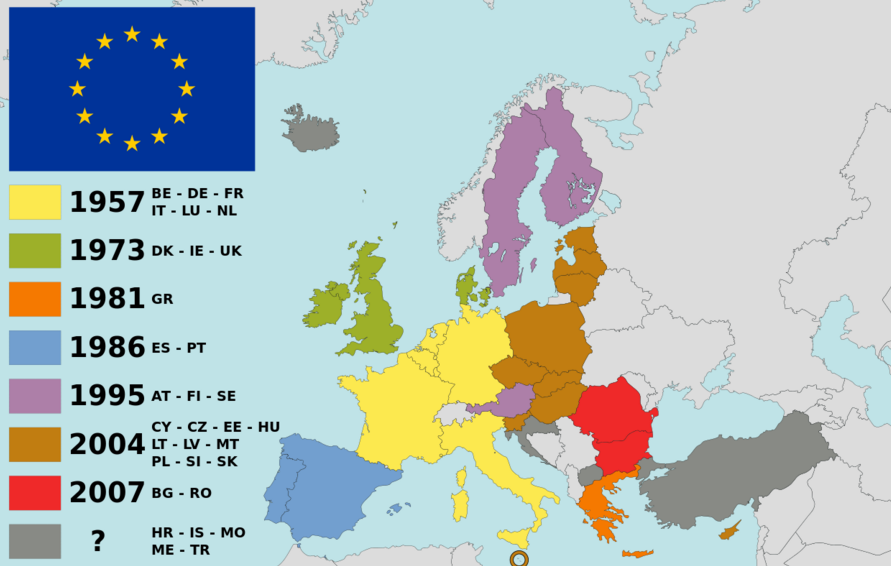

“Bowers and Mylles point out that in 1975 the debate was about membership of a trading bloc, the Common Market. For sure, the commitment to “ever closer union” was in the Treaty of Rome, but in 1975 few in the UK, especially in the yes campaign, paid much attention to it. Since then the EU has grown from 9 to 28 members, expanded into Central and Eastern Europe, created the Single Currency and acquired more characteristics of a federal union.

A 2016 or 2017 EU referendum seems likely to have a more political flavour than the 1975 vote, with a focus on the benefits and costs to the UK of a more ambitious, integrated, federal-like Union. This may well prove a tougher sell for the yes campaign than the trade and economic arguments that won the day in 1975.

In 1975 the UK economy was in a shambles, slipping into the role of sick man of Europe. In the previous three years the UK had endured a recession, double digit inflation, endemic industrial unrest and the imposition of a three-day working week to save scarce energy supplies. British voters in 1975 looked enviously to the prosperity and stability of Germany.

Today the UK is seeing growth of 2%, while the euro area grapples with the migration crisis, sluggish activity and the difficulties of building a durable monetary union. On a relative basis the performance of the UK economy looks, for now at least, pretty good. The burning platform of UK economic failure which helped win the 1975 referendum is absent.

The salience of migration in the Europe debate today marks another difference from1975. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 established the right of people to live and work anywhere in the EU, but as Bowers and Mylles observe, it was EU enlargement into Central and Eastern Europe in 2004 that caused immigration into the UK to rise markedly, pushing migration up the list of UK voter concerns. More recent migration from North Africa and the Middle East, and the growing problems facing the Schengen nations, have added new concerns. Migration levels in 2015 are already at all time highs of 336,000.

The final factor cited by Bowers and Mylles was the enthusiasm of the majority of the press for the Common Market in 1975. The press gave the then Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, largely uncritical coverage of his negotiations for a “better deal” in Britain’s relationship with the Community. (Historians tend to the view that Wilson actually achieved little in his negotiations with the Community; but he deftly turned meagre result into a public relations triumph). The lone dissenting voice in a general mood of press enthusiasm for the EEC was the Communist Morning Star. This time round it seems likely that a number of major papers will take a euro sceptic line. And it is inconceivable that the media will be as uncritical in its assessment of the Prime Minister’s current negotiation with the EU as it was in 1975.

The bookies odds and the polls suggest that the most likely outcome is that the UK will vote to remain in the EU.

But that is clearly not assured – and it’s certain to be a closer run thing than the landslide yes vote in 1975”.

0 Comments