Current Account Deficit: 2014-15

5th September 2015

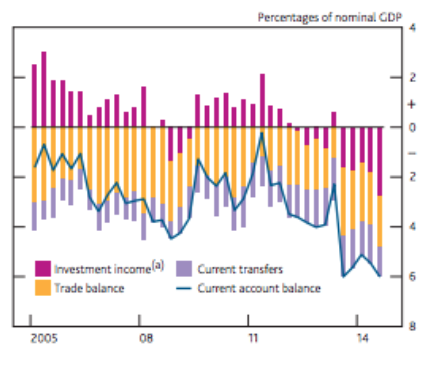

In 2014 Q3 the current account deficit, representing the difference between Export and Import values (X-M) in the Aggregate Demand (AD) equation, equalled its record of 6% of GDP. For example, in 2014Q3 our balance of trade in goods was a deficit of £32bn, offset by a surplus on services of £23bn. The effect on UK growth therefore remains negative to the tune of £9bn for that quarter. Import growth continues year on year whilst export growth has been stagnant since 2010. This is due to three factors:

1. The weakness of the world economy particularly in the eurozone means that unless there is a marked improvement in UK competitiveness, UK demand for European imports outstrip European demand for UK X.

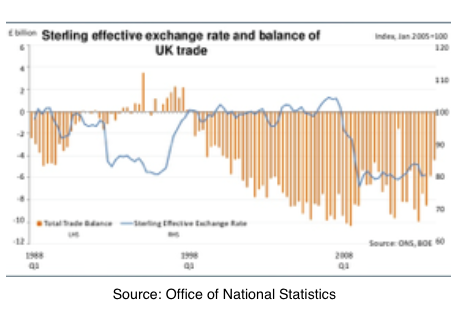

2. UK effective exchange rate (EER) appreciated 11% from March 2013 to February 2015. This a trade- weighted index which reflects the movement in the exchange rates of our trading partners. EU countries form 70%, and the US, 17%

of the index. Sterling continues to strengthen against the euro, so that in euro which almost reached parity in 2010, traded at the beginning of March 2015 at 73.0 – a weakening of the euro of 27%. This means UK imports are ceteris paribus cheaper, and UK exports more expensive, potentially affecting our trade balance with Europe. The ceteris paribu assumption is important – there are many factors affecting the price of imports (such as commodity prices worldwide, or the inflation rate in another country).

3. Investment income – the money we earn on our overseas investments – has declined sharply in 2014.

The UK is expected to arrest the decline in export market share that was a feature of the pre-crisis decade, which means the negative contribution of (X-M) to GDP growth will be lower in future years. The recovery of productivity growth should boost export competitiveness via its effect on unit labour costs, a key measure of cost competitiveness of UK exports. In addition, relative growth rates in emerging economies are expected to slow, reducing the export market share taken away from mature economies like the UK.

Does the current account deficit matter?

The current and capital accounts of the balance of payments must equal zero, in other words, every pound that flows out due to our trade imbalance must be matched by a corresponding inflow of investment money on capital account. For example, the Chinese current account surplus has been used to buy US bonds, and China now holds 7.2% of total US debt. China is, by this process of capital outflows, finding a way of bringing current account and capital into equality.

The UK has experienced a current account deficit since 1984, and Australia since 1974. Similarly, the USA during its period of C19th development imported financial capital to make up for shortfall in domestic savings. This was ploughed into capital stock (Investment) which yielded higher future growth rates as the US production possibility frontier shifted outwards year after year. Consequently, the US was able to run a current account surplus and invest abroad through capital outflows during much of the C20th.

Following the abolition of exchange controls in 1979 (which limited financial movements abroad) the UK has relied on overseas inflows of money to fund this deficit – inflows into UK assets such as Government bonds or property. One argument goes like this: the current account doesn’t matter as long as it can be financed by capital inflows at an acceptable rate of interest. And interest rates remain at historic lows.

But a counter-argument might be this: the free movement of capital distorts the price of UK assets. Just look at what foreign investment in London property has done to London house prices and you can see that it has a profound supply-side effect in reducing the ability of the labour market to move house to where the jobs are. It also reinforces the long-run deindustrialisation of Britain by causing the exchange rate to be higher than it otherwise would be. As a result our economy becomes unbalanced – relying on consumer spending to drive growth.

So is the deficit a problem? In the short term, no, as long as it can be financed by attracting foreign investment. But in the long-run, quite possibly, as long term structural problems become exaggerated.

0 Comments