Macroeconomic Core Concept 2: Aggregate Demand

17th September 2015

The Idea of Aggregate Demand

Aggregate Demand is the sum of all components of expenditure in the economy. Relating this to Macroeconomic Core Concept 1, the circular flow, we can say it is the sum of household expenditure, company expenditure and Government expenditure flows. In an open economy, we can add the influence of net exports, (X – M). In the analysis below, we introduce the Keynesian 45 degree line which represent a set of equilibrium points where expenditure equals output. Keynes was interested in the dynamics of a movement of national income upwards (recovery) or downwards (recession) which can be explained by this simple model. The Keynesian multiplier, introduced by Macroeconomic Core Concept 3, explains how the dynamics of changes in national income occur.

Keynes recognised that the total quantity demanded of an economy’s output was the sum of four types of spending: consumer expenditure (C) , planned investment spending (I), government spending (G), and net exports (X – M).

He argued that equilibrium would occur in the economy when total quantity of output supplied (aggregate output produced, Y, below) equals quantity of output demanded (E), that is, when Y = E.

But the sum of these components could add up to an output smaller than the economy is capable of producing, resulting in less than full employment. There could, in other words, be permanent underemployment equilibrium which could persist over time. This was indeed the experience of the great depression of 1929-1936. Keynes identified the cause as a deficiency of aggregate spending, which could be made good by public works (G).

Aggregate expenditure

Aggregate Demand or aggregate expenditure has four components that together make up the AD equation.

- Consumer Spending. This comprises two-thirds of aggregate expenditure and is particularly sensitive to the cost of borrowing – the interest rate level which is currently at an all time low.

- Investment spending. Keynes believed that investment spending was a prime cause of the business cycle or fluctuations in real GDP, because investment comprises expenditure on capital stock plus inventories. Inventories, or unsold stock, rise sharply in an economic downturn and a exaggerate any movement in aggregate expenditure.

- Government Spending. Governments engage in both capital spending (on roads or hospitals) and current spending, on goods, services and wages.

- Net trade or exports minus imports (X-M). Both goods and services are traded across exchange rates and if net exports are positive, contribute a positive element to aggregate spending.

Equilibrium in the closed economy

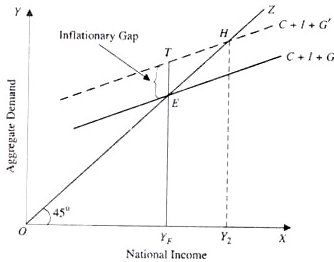

The 45 degree line below represents a set of equilibrium points where Aggregate sending equals aggregate output (or real GDP) ina closed economy where aggregate demand is given as:

Y = C + I + G

Any point to the left of the intersection of aggregate demand with the 45 degree line represent points of disequilibrium – where economic activity will be either expanding or contracting.

Any attempt to expand beyond full employment (OYF) will open up an inflationary gap.

Now, aggregate demand YFT is greater than aggregate demand YFE which is required to maintain the equilibrium at OYF. Thus with the level of aggregate demand (C + I + G’), which is obtained by adding expenditure ET to the aggregate demand curve C + I + G, the level of nation income would be greater than OYF.

Since OYF is full-employment level of national income, actual production cannot increase beyond this level, so we predict there would be rise in prices, which would raise the money value of OYF production. The amount by which aggregate demand exceeds the level of full employment national income is called an inflationary gap due to the upward pressure on domestic prices which results.

The excess of aggregate demand or inflationary gap is equal to ET. The aggregate demand curve C + I + G’ intersects the 45° line (OZ line) at H, so that equilibrium level of national income would be OY2.

There is no difference between OYF and OY2 in terms of real income or actual production; only as a result of a rise in price level, national income has increased from OYF to OY2 only in money terms. The inflationary gap represents excess demand in relation to aggregate production or supply of output, which produces demand-pull inflation.

J.M. Keynes in his “General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money” did not discuss the concept of inflationary gaps because he was seeking to explain the state of depression and deflation. During the Second World War when inflation rose, Keynes applied his macroeconomic analysis to explain inflation and put forward the concept of an inflationary gap.

Deflationary Gap

The concept of deflationary gap explains how unemployment and economic depression occur. According to the Keynesian theory of income and employment, equilibrium at the level of full- employment is established when aggregate demand (C + I + G) is equal to national income at the level of full-employment.

This happens when investment and government demand is equal to the level of savings (or consumer spending shortfall) at full-employment level of national income. If aggregate demand is less than the full-employment level of national income, the deficiency of aggregate demand causes a fall in real GDP.

Unemployed resources will result.

A Diagrammatic Representation

The equilibrium level of income and employment below would be established at OYF, (see below) when aggregate demand is equal to YFE (which is equal to national income OYF). But in the real world if aggregate demand is less than the full-employment level of income OYF (less than YFE), then a deficiency of aggregate demand drives real GDP downwards.

When the aggregate demand curve is C + I+ G’ (the dotted line) there will be a deflationary gap equal to EK. The aggregate demand curve C + I + G’ (dotted) cuts the 45° line at point Q which produces OY0 level of national income. This is therefore the new equilibrium where Y = E, given by the 45 degree line.

The deflationary gap represents the difference between the actual aggregate demand and the aggregate demand which is required to establish the equilibrium at full-employment level of income (OYf below).

Due to the deflationary gap EK, the level of national income and employment will fall. The fall in national income and employment will not only be equal to the deflationary gap EK but it will be much greater than this. This decline in national income is determined by the value of the multiplier discussed in Macroeconomic Core Concept 3.

As a result of this shortfall in aggregate demand, argued Keynes, involuntary unemployment in the economy persists. The depression of 1929-33 was caused by the emergence of a deflationary gap, or by a general (and seemingly persistent) deficiency in aggregate demand. He called on Governments to make that deficiency good by public works programmes – a call heeded in the US by President Roosevelt’s New Deal and ultimately solved in the UK by the coming of the second World War.

0 Comments