Should We Worry About China’s Slowdown? (Sept 2015)

17th September 2015

Should we worry about China’s slowdown?

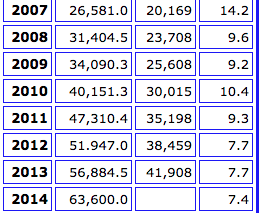

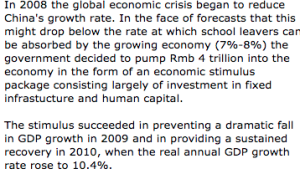

China is struggling to achieve it’s economic growth forecast of 7% for 2015 (see Table of GDP at constant prices (col 1), GDP per capita (col 2), and Chinese growth rates (col 3)). It is a far cry from the heady days when China achieved year on year growth of 10%. The question is. should we worry?

The OECD report released today, September 17th 2015, warns that the global economy is stagnating. Although its  forecast for the UK growth rate for 2015 remains unchanged at 2.4% , it also predicts that a Chinese slump could take £4.6bn out of the world economy over the next two years. How can this happen?

forecast for the UK growth rate for 2015 remains unchanged at 2.4% , it also predicts that a Chinese slump could take £4.6bn out of the world economy over the next two years. How can this happen?

The circular flow of income is our Macro Core Concept 1. Just as there is a flow of money around the UK economy in the form of injections of money (consumer spending for example) and withdrawals (imports for example) so there is a giant circular flow happening in the world economy.

As China grows, it demands more UK imports (an injection of export earning s into the British economy). And China lends money to the USA by purchasing US bonds, reflecting in a capital account  flow to the USA. Even the humble Chinese student studying in the UK represents an inflow of export earnings across exchange rates into the UK banking system.

flow to the USA. Even the humble Chinese student studying in the UK represents an inflow of export earnings across exchange rates into the UK banking system.

So if China slows down, what happens? Effectively it is injecting less money into the world economy and also it has less money to lend to the world. This net withdrawal, relative to previous forecast, is represented by that OECD figure of £4.6bn.

A multiplier effect will result – lower Chinese injections mean lower growth rates for the rest of the world as Chinese contributions to the world economic growth decline. Just as there is a Uk multiplier (whose value is around 2) so there is a world economic multiplier.

So why is this going to have negligible effect on UK growth rates? Well, China is not a big source of UK exports.

Imports of goods and services from China have grown from £11.3 billion in 2004 to £37.7 billion in 2014. Exports have grown at a slower rate, from £4.0 billion to £18.2 billion, and accounted for just 3.6% of UK exports. Because imports have grown at faster rate than exports, the UK’s trade deficit with China has also grown. Our trade deficit stood at £19.5 billion in 2014, the second highest behind Germany. So if China slows down this net deficit might get smaller – in other words, the net withdrawal from UK circular flow could actually be less. Likelihood is it will actually increase because, although 7% is a lower growth rate, it is still positive and three times that of the UK.

Traditionally we trade with Europe and the USA as the first two major blocks, and other countries form lesser contributions to our export markets. This is partly a damning comment on our cultural heritage –we don’t tend to learn mandarin or think in terms of China as a key market. All this should change, and hopefully will do as schools embrace mandarin. A recent Government Report comments:

“Part of the reason the UK underperforms in China is because China’s import demand is not well aligned with the UK’s sectors of comparative advantage. The more China rebalances, the greater the share of the market the UK could capture. Significant rebalancing could add up to £20bn to UK exports by 2020 – 90% of which comes from 4 sectors: cars, pharmaceuticals, financial & business services. Arguably it is these sectors where HMG should focus its lobbying effort – to open them up. The other reason the UK underperforms in China is because UK businesses are not doing as well as they are in other countries. Matching the UK’s performance in other markets could add up to £60bn to UK exports. 58% of these gains are concentrated in six sectors: machinery, business services, transportation services, precision instruments, insurance and organic chemicals. Arguably it is these sectors where HMG should focus its effort on encouraging UK businesses to engage”.

In the mean time, our relatively poor export record has ensured that shocks administered to the world economy by China have relatively little impact on the UK.

Peter Baron

Manging Editor peped.org

0 Comments