Should Railways be Renationalised?

2nd October 2015

Should railways be renationalised?

The Labour Party wants it, the Conservatives disagree: Patrick McCloughlin, Conservative Minister, celebrated the twentieth anniversary of the privatisation of British Rail (1993) with a speech which heralded “20 years of rising investment and 20 years of extraordinary growth on our railway”:

“As a junior transport minister in the 1980s, I remember British Rail. Underinvestment in tracks and trains. Poor reliability. Managers whose good ideas were too often stifled by a lack of cash and an ageing network in a declining industry. For most of the time since the Second World War rail traffic has been falling. Since privatisation, journeys have doubled. The network is roughly the same size as 15 years ago. But there are 4000 more services a day. This is the success of privatisation”.

But is this rather starry-eyed view justified? What would be the economic effects of renationalisation?

Partial privatisation

Rail was privatised in two stages. In 1993 Railtrack was created to run the network. Now called Network Rail, this is nominally a ‘private’ company which depended on government guarantees to underwrite its bonds at a lower interest rate. Network Rail has also received significant direct state subsidies. In Dec 2013 network rail was officially reclassified as a “Central Government Body’ and now raises loans directly from the Treasury. Current subsidies run at £4bn a year, up from £2.75 bn in 1989 (at constant prices).

From 1997, the train operators were split into 25 franchises and companies bid for a five year licence. Rolling stock was leased from a separate firm. Since then there have been continual complaints about overcrowded trains, poor service punctuality and underinvestment in track (such as the long over due electrification of the west coast line).

The flaws in the Railtrack business model were exposed by a succession of fatal rail accidents at Southall in 1997, Ladbroke Grove in 1999, Hatfield in 2000, and Potter’s Bar in 2002. Subsequent official inquiries exposed serious underinvestment in track and signalling, and an outsourcing strategy which raised the costs of new investment projects by 2–3 times the levels paid by British Rail.

Contestable market

The franchise operators exist in what economists call a contestable market. They are effectively granted a short – term monopoly in the hope that, with few barriers to entry and zero sunk costs (the investment burden is taken by the track operator Network Rail), companies will fear the possibility of new entrants grabbing their franchise, either due to poor quality of service or arguments about ticket pricing. Two franchisees failed in quick succession: Great North Eastern Railways in 2007, and National Express East Coast in 2009 after making what proved to be excessively optimistic estimates of the revenues they would receive and the franchise payments they could thereby afford.

Demand and supply

Despite the deficiencies train usage has soared. In 1995-6, trains carried 761m passengers which by 2013-14 had risen to 1.58bn. Demand had doubled. But the supply of trains and track has not doubled. The result is overcrowded trains, limited by length of platforms to the carriages they can operate, poor reliability and continued postponement of major new investment. The HS2 high speed track will grind slowly to fruition (if after public protests, it ever happens at all).

Renationalisation

So the privatised rail industry is arguably not a pure form of privatisation but an attempt to bring elements of the theory of contestable markets to generate efficiency improvements. Large-scale private investment has not been forthcoming. According to KPMG, the train operators generate between them around £300m profit or 3% of turnover – exactly the same as in 1997 under state ownership.

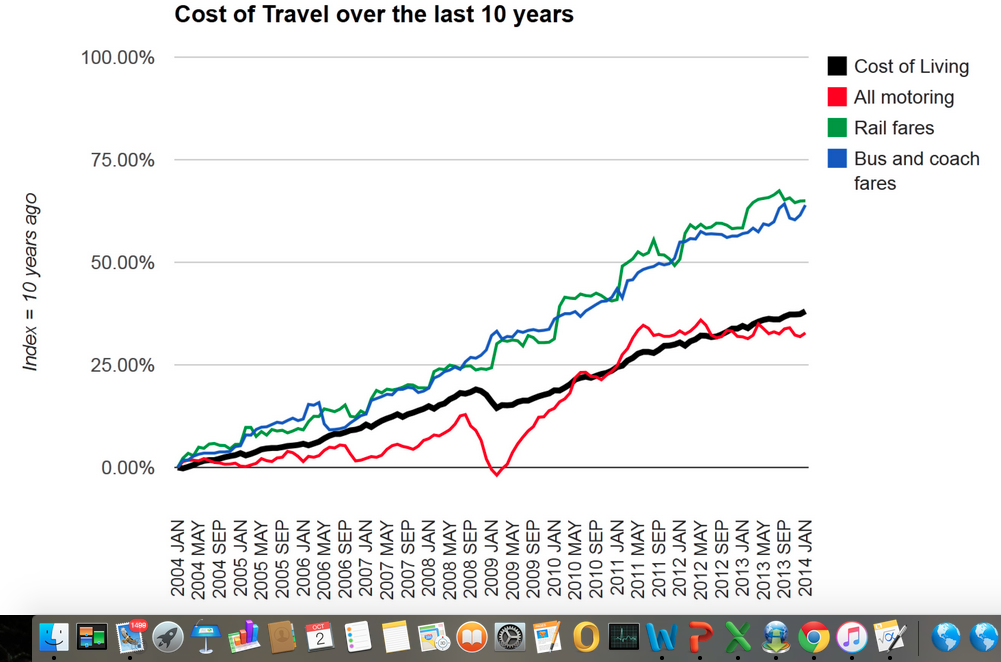

However, fares have outstripped inflation (see below). Surprisingly, in real terms, rail has also outstripped the cost of motoring. Depending on the method of  accounting, operators are accused of making much larger returns than declared. The issue is complex: as a bidder for a franchise you have to declare how much money you intend to make. If you make more than this, the Treasury takes 80% of the surplus. Too little, and the Government produces a subsidy. This is hardly free market economics as we know it – more like whistling into the wind and hoping the figures turn out right.

accounting, operators are accused of making much larger returns than declared. The issue is complex: as a bidder for a franchise you have to declare how much money you intend to make. If you make more than this, the Treasury takes 80% of the surplus. Too little, and the Government produces a subsidy. This is hardly free market economics as we know it – more like whistling into the wind and hoping the figures turn out right.

Would nationalisation make any difference? Well it would cost something – the loss of franchise revenue, but what happened next would depend on the quality of management and industrial relations. Management under British Rail was accused of being poor – it is an X-efficiency gain that managers in the private sector have greater incentive to manage effectively and efficiently. And strikes were often seen to be against the Government in the nationalised regime – because a Government can, after all, it is reasoned, afford to pay.

Chris Blackhurst concludes in the Independent (1.10.15): “if renationalisation reinstalls a cadre of managers who can beat up suppliers and produce the best deal for passengers, all will be well”. Perhaps that’s optimistic: we have still to find the right compromise between competition and monopoly within the UK rail services in way that delivers true efficiency gains and improvements in quality of service.

0 Comments