Article: What Are Bank Reserve Assets For?

25th September 2015

source IMF

THE PURPOSE OF RESERVE REQUIREMENTS (RRs)

A. Prudential

RRs ensure that banks hold a certain proportion of high quality, liquid assets. In the days of the gold standard, banks might hold gold—either directly or with another bank— 8 as backing for deposits received or notes issued,4 but reserves cover could only be partial if banks were to conduct any lending business funded by deposits. This structure of partial reserve cover is sometimes referred to as “fractional banking”—banks held reserve assets equivalent to a fraction of their liabilities—particularly short–term liabilities, where outflows could happen most rapidly and liquidity cover was therefore most important.

Initially the level of reserve cover was voluntary, but over time these reserves were centralized in central banks, which mandated the level of reserve coverage required. In the United States, from early in the 19th century until 1863 when the National Bank Act was introduced (setting RRs for banks), many banks held reserves—typically, gold or its equivalent—informally with other commercial banks in return for an agreement by that bank to accept their banknotes.5 Individuals would be more willing to use notes issued by Bank A if they knew that issuance was backed (if only partially) by reserves, and that at least some other banks would accept those notes; and Bank B would clearly be more willing to accept Bank A’s notes if they had some reliable backing.

This is similar to ideas discussed by Bagehot in Lombard Street (1863), where he suggests that banks should hold more than enough reserves—essentially, gold or balances at the central bank—to meet likely short–run demand.6 12. Short–run demand—a net drain on the banking system’s reserves—could come from two sources: the need to make payments abroad, or a domestic panic. In the case of an international drain, foreign currency (or gold) is needed, and interest rates may be increased to reverse the drain. In the case of a domestic drain, central bank lending of domestic reserve money is required. In the post gold standard world, domestic currency reserves are only likely to be able to cover domestic liquidity needs. Reserves to cover international needs belong to the sphere of foreign exchange reserves management, where different policy issues arise.

6 “A good banker will have accumulated in ordinary times the reserve he is to make use of in extraordinary times.”

At the time he was writing, the Bank of England was de facto the reserve bank (it held gold reserves for the banking system as a whole), but de jure was a private bank with no legislative authority over the system.

The fractional reserve approach gave added confidence to the use of private sector money (such as notes issued by commercial banks). It was bolstered by the banks’ ability, over time, to resort to borrowing from the central bank. Until the 20th century, this was largely informal (Bagehot complains in ‘Lombard Street’ of the importance of such a role in the United Kingdom being entrusted to the Bank of England without any parliamentary authority or government guidance). In the United States, the creation in 1913 of the Federal Reserve Bank system meant that a reliable central bank could lend “reserves” (here meaning: central bank balances, which could if necessary be converted into gold) to member banks. This form of support is primarily related to liquidity, as it would allow commercial banks, up to a point, to cope with a bank run.

But it also has elements of solvency, since the reserves held by the commercial banks with the central bank should be of the highest credit quality. But the prudential and ‘safety net’ benefits are in most cases now covered— more effectively—by a combination of supervision and regulation (with appropriate capital adequacy and liquidity requirements), deposit insurance, and standing credit facilities provided by the central bank. Moreover, as discussed below, the prudential role of reserves is substantially weakened where reserve averaging is permitted.

In 2010, over 80 percent of central banks permitted at least some element of reserve averaging. Where the prudential (liquidity and solvency) goals of RR can be met more effectively and efficiently with other approaches, the prudential role of RR may be outdated. Central bank balances will still likely form part of the liquidity management of commercial banks, but a standardized administrative requirement on all banks is not obviously the best way to promote this. Supervisors would certainly be expected to count central bank balances as highly liquid assets, and would expect banks—particularly those with important business in the large value payment system of the country—to hold a certain level of central bank balances. But other assets would also likely be included, such as short– term government securities.

B. Monetary Control

The uses of RRs for monetary control are normally described in terms of two channels: the money multiplier, and the impact of RR on interest rate spreads. The money multiplier and control of credit growth 18. The money multiplier approach assumes that banks increase their loan portfolios until constrained by reserve requirements, on the assumption that the supply of reserves is constrained.

If a minimum fraction of commercial bank borrowing needs to be covered by reserves (gold), then the availability of reserves (gold) must necessarily limit bank borrowing, and thereby its capacity to lend.8 (Credit funded by non–reservable liabilities would not be so constrained.) Under a currency board system (or the gold—or other specie—standard), reserve money creation is constrained by the requirement that it be backed by specified assets. Central bank purchase of foreign exchange or gold provides an external backing to reserve money; the purchase of government securities may also provide backing, but is closer to secured lending.

If reserve creation is constrained, a higher reserve requirement would then necessarily force a reduction in lending, while a lower requirement would permit an increase. But this description does not reflect modern central banking practice.Once “reserves” comes to mean “balances at the central bank,” the central bank can easily accommodate any increase in the demand for reserves—provided banks hold adequate collateral—since it can create them.

Using control over reserve money to guide credit growth in a fiat money system is in practice an indirect means of using interest rates. Instead of restricting the availability of reserve money completely – an action that could provoke fails in the payment system – central banks in many countries restricted the amount of reserves which could be funded at or around the policy interest rate. Assume for instance that a central bank estimates the market to be short of 100 in reserve balances. It could lend 100 via its OMO at market rates (assuming that market rates are in line with the policy target). Or if it wanted market rates to rise, it could lend only via OMO at market rates, forcing banks to fund the remaining 50 via the standing credit facility. If banks had to borrow larger amounts at the higher standing credit facility rate (the Discount, or Lombard, or Bank Rate) their overall cost of funding would rise, and this would be passed on to customers.However, in recent years central banks have increasingly adjusted the policy rate explicitly rather than expecting the market to infer it from the balance of reserves supplied between OMO and a standing credit facility, and taken an accommodative approach to reserve money supply (so that the expectation is that the standing credit facility will almost never be used).

This allows a distinction to be made between the monetary policy stance and reserve money (or liquidity) management.  The discussion applies also to situations of a structural surplus of reserve balances. The central bank could aim to drain the surplus via OMO, at or around the targeted market rate and change the announced rate if a change in policy stance was required; or drain only part of the surplus via OMO, leaving the remainder to be remunerated at the interest on excess reserves/standing deposit facility rate. The result would be that market interest rates would be expected to fall below the policy rate.

The discussion applies also to situations of a structural surplus of reserve balances. The central bank could aim to drain the surplus via OMO, at or around the targeted market rate and change the announced rate if a change in policy stance was required; or drain only part of the surplus via OMO, leaving the remainder to be remunerated at the interest on excess reserves/standing deposit facility rate. The result would be that market interest rates would be expected to fall below the policy rate.

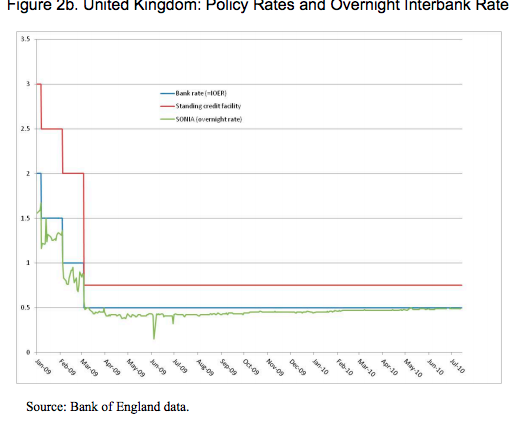

In the United Kingdom and the United States at present, the Interest on excess reserves IOER rate has become the key policy rate: all reserve balances are remunerated at a single rate, and there are no short–term OMO. Figures 2.a and 2.b below indicate that IOER will not necessarily set a floor to targeted money market rates, if these are not pure interbank rates.

In the United Kingdom, the effective sterling overnight rate (SONIA), like the US FFR, is not a pure interbank rate; but Sterling overnight LIBOR and the highest transaction rate in the SONIA data have been around 5bp above the IOER rate.

0 Comments