Government options for a Green Policy

A market economy ensures that producers supply goods that consumers want, at a price they are willing to pay. A market economy does not guarantee an outcome which benefits society as a whole. Firms and consumers may not take all external costs into consideration. Firms will only supply good which are less damaging to the environment if they feel that there is a market for that good, or unless they are compelled to do so by legislation.

In an open economy a major issue is whether regulation of industry impairs the international competitiveness of a country. If this is the case then regulation may have an impact on a country’s balance of payments, terms of trade, national income and domestic employment. A major concern for government is how it can control negative externalities with the least harm to its economy.

Pollution may occur during the production process, but it may also occur during the consumption, use or disposal of goods. Where the government targets pollution arising during the production process it generally leads to an increase in production costs. This in turn is likely to have a knock on product prices because of the higher costs incurred by the producer. Higher prices passed on to the consumer might result in a loss of international competitiveness.

One strategy to reduce pollution is to pay polluters not to pollute,. Those affected by pollution could pay the polluter to reduce production. This principle was adopted under the Kyoto Protocol. Under Article 11 of the Treaty developed countries agreed to provide financial assistance to developing countries to support measures to reduce greenhouse emissions.

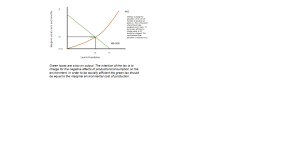

A second strategy which government could adopt would be to levy environmental charges. These charges could either be imposed on firms or on consumers. Producers could be charged emission charges based on the level of their emissions. Emission charges could be imposed on households for disposal of waste. In order to achieve social efficiency the optimum level of environmental use would be at the point where marginal social costs and benefits were equal. If no charges were imposed for the pollution the marginal private costs would be zero. Firms would continue to produce until point e1 was reached.

A third approach to pollution would be to impose taxes on the output/consumption of a good where external environmental costs are generated.

The alternative to charging for pollution is to charge for consumption where pollution occurs. These taxes are frequently referred to as ‘green taxes.’

Green Taxes

Green taxes have become increasingly popular with governments if not with consumers. Green taxes have the advantage over regulations to control pollution, because the level of tax can be adjusted to reflect the amount of pollution. High levels of pollution will incur high levels of tax. The effect of green taxes is to increase the price of goods. In order to achieve a socially efficient output, the rate of tax should be equal to the marginal cost.

One of the problems of imposing green taxes is the amount of information needed. In order to impose green taxes on producers the government would need to know:

- The firm’s existing and planned level of output

The level of pollution generated by this level of output

The extent to which their has been a long term accumulation

The government may also seek to curb pollution by offering incentives which encourage consumers or producers to reduce pollution. A range of government initiatives exist encouraging consumers to replace existing bulbs with low energy bulbs, or to insulate lofts and replace hating boilers in order to improve energy efficiency. The level of subsidy paid should be equal to the marginal external benefit.

It is often argued that the polluter should pay the full cost of pollution. Often this is not the case. Green taxes and subsidies are not a perfect solution. If government imposes a tax on producers it is likely that the producer will try to pass some of the tax burden onto consumers. The ability of the producer to do this is dependent upon the price elasticity of demand.

One of the dilemmas of employing taxes to reduce pollution is that it may have a disproportionate effect on the poorest in society. Taxes on gas and electricity consumption are regressive. This is because the poorest in society will spend a greater proportion of their income on heating and lighting.

When considering the effectiveness of taxation, it is worth considering what should be done with the tax revenue. Tax income could be used to subsidise green alternatives. The government has chosen not to direct the majority of green tax revenues this way. Instead these taxes have been used as an additional source of revenue.

The recent downturn in the UK economy has caused the government to reflect upon its policy of imposing taxes fuel. It has delayed the introduction of tax increases on fuel in order to try and boost the economy. Just because it is the ‘right’ thing to do, does not mean that the government will always do it, particularly if the changes are likely to affect popularity or harm the economy.

There are other alternatives to imposing taxes on producers and consumers. Instead government could seek to introduce voluntary agreements (VA’s) in an effort to encourage firms to reduce pollution. VA’s may be formal agreements with legally binding contracts or may be informal.

Firms may chose to enter into VA’s because they see a commercial benefit. If firms believe that they are likely to gain sales or improve their public image they may be willing to enter into this form of agreement.

Firms often find VA’s more acceptable than regulation because they have the opportunity to negotiate such arrangements to suit their own particular circumstances and incorporate them into their planning. This may allow firms to adapt processes gradually achieving improvements at a lower cost than if changes were dictated by legislation.

Whether VA’s are effective or not depends to a large extent on how tightly the measures were drawn up; the rigour with which government inspectors monitor compliance and the temptation fr firms to bend the terms of agreements so that they can avoid having to reduce emissions by as much as was originally intended.

Public attitudes can determine the environmental consequences of their actions. People do not always act out of self interest. They may also act for the public good. If public god and self interest can be married together then, all the better. Consumers have become increasingly ‘green’ buying environmentally friendly washing up liquids, conditioners and energy efficient electrical goods.

Education has a role to play in encouraging consumers to buy environmentally friendly goods even if they are more expensive. The government has invested heavily in a number of environmental campaigns in order to promote recycling and increase energy efficiency. Educating customers can exert pressure on manufacturers to modify products through market forces. Increasing demand for environmentally friendly products and falling demand for more harmful products may encourage firms to reallocate resources.

The problem of global warming

The output of greenhouse gases is high in the developing world. This places the European Union and other developed countries in a quandary. Reducing emissions of greenhouse gases is expensive but will create benefits. The problem is that there is no incentive for the European Union to act alone. The costs for the European Union would be high but the benefits would be minimal if the member countries acted alone. Other countries outside European Union would benefit from the action of the European Union to limit pollution without incurring any of the costs. In order to ensure widespread compliance with environmental initiatives international treaties could be negotiated. In order for these treaties to be effective there must be incentives for those countries signing the agreement. Various attempts have been made including the climate convention (1994) which sought to limit the output of greenhouse gases by 60 countries. This convention required countries to return to 1990 emission levels by 2000. To achieve this, high energy taxes were needed in order to encourage a substitution effect towards cleaner fuels. Without substantial taxes there is little incentive to adopt more expensive energy sources. However, many countries remain resistant to energy taxes.

Tradeable Permits

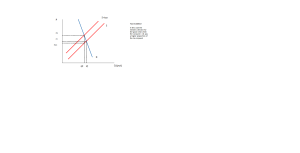

Tradeable permits have grown in popularity. Tradable permits seek to combine market incentives with command and control measures. Maximum permitted levels of pollution are set for each firm. The firm is then given a permit to produce pollution up to that level. If the firm is efficient and produces less pollution then it can gain a credit which can be sold to less efficient producers who exceed their permitted levels. The command and control system determines the overall level of pollution and the market mechanism will distribute the right to pollute.

This system of tradeable permits can operate on an international level with countries trading quotas. The system can be used not only to control emissions from factories but also to allocate fish stocks in order to prevent the depletion of fish stocks.

The principal advantage of tradeable permits is that they put in place upper limits for pollution and can ensure a gradual reduction of overall pollution limits. Governments can set the overall limit for allowable discharge according to the ability of the environment to absorb pollution. The market allows the reduction in pollution to be achieved at the lowest possible cost.

Overall limits are often based on the current levels of pollution. Reductions are achieved by requiring firms to reduce emissions by a given percentage. The big drawback to this approach is that efficient firms who are already using the most efficient production methods may be penalised. This is because the may have less scope to make further improvements. Cuts may also be more expensive to achieve.

There are other concerns about tradeable permits. The imposition of tradeable permits may lead to production being concentrated in certain countries as producers buy up emission quotas from other countries.

Landfill

In an effort to reduce landfill waste in England and Wales by two-thirds, the Government has launched a public consultation on a system of tradeable landfill permits. It is intended that the scheme will ensure that the UK complies with European Union rules which require the amount of biodegradable municipal waste being consigned to landfill to be cut to 35% of 1995 levels.

Waste disposal authorities would be able to hold or trade in the permits. The scheme would allow any authorities investing in recycling to sell permits that they no longer require to authorities who remain reliant on landfill.

Landfill is becoming increasingly scarce. At the same time household waste is increasing by 3% every year. There is clearly a need for decisive action. According to the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR), the proposed system would provide certainty in meeting European Union targets, would be easy to administer, whilst allowing for consistency and accountability.

Task

Examine the likely impact of introducing tradeable landfill permits on business costs and international competitiveness