Financing the Fiscal Deficit

26th October 2015

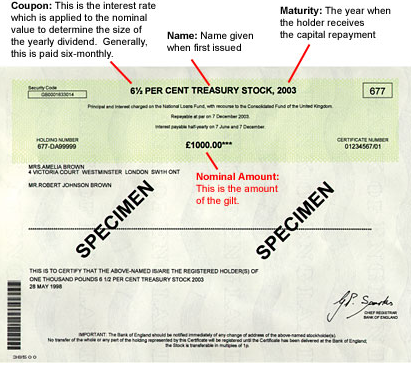

On October 20th the Government held a bond or gilt-edged stock auction. By this method it finances the Government deficit, forecast to be £69.5bn this year. Only what made this unusual was the length of term: it was £4bn of 50 year debt being auctioned at 2% interest rate (or yield). And secondly, it was unusual because most of the take-up in the auction was by pension fund managers buying financial assets to cover their future pension liabilities.

The bond auction coincided with Chancellor Osbourne’s tabling a Commons motion to commit the Government to fiscal surpluses ‘when conditions permit’.

The Charter sets out:

- a target for a surplus on public sector net borrowing in 2019-20 of £10bn, and a supplementary target for public sector net debt to fall as a share of GDP in each year from 2015-16 to 2019-20

- a target, once a surplus is achieved in 2019-20, to run a surplus each subsequent year as long as the economy remains in normal times

These targets will apply as long as the economy is not hit by a significant negative shock that reduces real GDP growth to less than 1% (on a rolling 4 quarter-on-4 quarter basis). If the OBR judge that the economy has been hit by a shock, the surplus rule will be suspended.

This is seen by the Government as a test of fiscal prudence. After all, future deficits need to be financed just as our deficit this year needs to be financed. Surpluses don’t need financing – they are used to pay off the national debt and reduce it’s overall level from its present level of £69.5bn (summer budget forecast, 2015, for fiscal year 2015-16). Deficits add to national debt – surpluses reduce it, and the national debt is simply the sum of all past deficits.

Except there may be a problem with the government logic here. The market- comprising those who buy the government’s assets, the bonds it sells like these fifty year bonds in October, is only requiring a 2% yield over time. And fifty years is a very long time. This is as low as the old War Loan the Government sold to finance the second world war, which were patriotically snapped up at 1.75% yield. Then we bought them out of a sense of national duty. Now the pension funds are buying them because they are confident inflation will not accelerate in the next fifty years, and because its seen to be safe as governments don’t go broke. And so a 2% yield is seen as a good bet. Financing national debt has never been easier or cheaper.

When someone buys a bond there are actually two factors to consider, the market yield and the market price. Imagine I buy  a 2% bond – if I wish to earn £2, then the price (and the face value on issue) of the bond is £100. £100 is the amount I will get back at redemption date in 50 years. But suppose interest rates go down to 1%. Then to yield the same £2 I will need to buy £200 worth of new bonds. As interest rates halve (2% to 1%) the price of the existing bonds, those issued last year when the yield was higher, doubles. And this law applies to all existing bonds, because they are being bought and sold in competition with new issues.

a 2% bond – if I wish to earn £2, then the price (and the face value on issue) of the bond is £100. £100 is the amount I will get back at redemption date in 50 years. But suppose interest rates go down to 1%. Then to yield the same £2 I will need to buy £200 worth of new bonds. As interest rates halve (2% to 1%) the price of the existing bonds, those issued last year when the yield was higher, doubles. And this law applies to all existing bonds, because they are being bought and sold in competition with new issues.

In 2008 bonds yielded 5%, and in 2013, 3.5%. So if I had bought a bond in 2008 the market value of my bond would have more than doubled as interest rates have halved from 5% to 2%. Not only would my return be good (5% on my initial outlay of money) but should I choose to sell my £100 bond, I would get £200 for it (or slightly more). From this we get a law: bond yields and prices are inversely related (they move in opposite directions).

In 2015-16 the government needs to raise £127bn by new debt issues, both to finance this year’s deficit and replace government stock that is being redeemed (whose expiry date has arrived). £25bn of this will be what is called ‘syndicated” – bought by fund managers. They are confident in the long term outlook of Britain’s economy, otherwise they wouldn’t risk pension fund money in this way.

0 Comments