Extract: Two Misconceptions about Money Creation

25th September 2015

The vast majority of money held by the public takes the form of bank deposits. But where the stock of bank deposits comes from is often misunderstood. One common misconception is that banks act simply as intermediaries, lending out the deposits that savers place with them. In this view deposits are typically ‘created’ by the saving decisions of households, and banks then ‘lend out’ those existing deposits to borrowers, for example to companies looking to finance investment or individuals wanting to purchase houses.

In fact, when households choose to save more money in bank accounts, those deposits come simply at the expense of deposits that would have otherwise gone to companies in payment for goods and services. Saving does not by itself increase the deposits or ‘funds available’ for banks to lend. Indeed, viewing banks simply as intermediaries ignores the fact that, in reality in the modern economy, commercial banks are the creators of deposit money.

Rather than banks lending out deposits that are placed with them, the act of lending creates deposits — the reverse of the sequence typically described in textbooks.(3) Another common misconception is that the central bank determines the quantity of loans and deposits in the economy by controlling the quantity of central bank money — the so-called ‘money multiplier’ approach. In that view, central banks implement monetary policy by choosing a quantity of reserves. And, because there is assumed to be a constant ratio of broad money to base money, these reserves are then ‘multiplied up’ to a much greater change in bank loans and deposits.

For the theory to hold, the amount of reserves must be a binding constraint on lending, and the central bank must directly determine the amount of reserves. While the money multiplier theory can be a useful way of introducing money and banking in economic textbooks, it is not an accurate description of how money is created in reality. Rather than controlling the quantity of reserves, central banks today typically implement monetary policy by setting the price of reserves — that is, interest rates.

In reality, neither are reserves a binding constraint on lending, nor does the central bank fix the amount of reserves that are available. As with the relationship between deposits and loans, the relationship between reserves and loans typically operates in the reverse way to that described in some economics textbooks. Banks first decide how much to lend depending on the profitable lending opportunities available to them — which will, crucially, depend on the interest rate set by the Bank of England. It is these lending decisions that determine how many bank deposits are created by the banking system. The amount of bank deposits in turn influences how much central bank money banks want to hold in reserve (to meet withdrawals by the public, make payments to other banks, or meet regulatory liquidity requirements), which is then, in normal times, supplied on demand by the Bank of England. The rest of this article discusses these practices in more detail.

Money creation in reality

Lending creates deposits — broad money determination at the aggregate level As explained in ‘Money in the modern economy: an introduction’, broad money is a measure of the total amount of money held by households and companies in the economy. Broad money is made up of bank deposits — which are essentially IOUs from commercial banks to households and companies — and currency — mostly IOUs from the central bank.

Of the two types of broad money, bank deposits make up the vast majority — 97% of the amount currently in circulation.  And in the modern economy, those bank deposits are mostly created by commercial banks themselves Commercial banks create money, in the form of bank deposits, by making new loans. When a bank makes a loan, for example to someone taking out a mortgage to buy a house, it does not typically do so by giving them thousands of pounds worth of banknotes. Instead, it credits their bank account with a bank deposit of the size of the mortgage.

And in the modern economy, those bank deposits are mostly created by commercial banks themselves Commercial banks create money, in the form of bank deposits, by making new loans. When a bank makes a loan, for example to someone taking out a mortgage to buy a house, it does not typically do so by giving them thousands of pounds worth of banknotes. Instead, it credits their bank account with a bank deposit of the size of the mortgage.

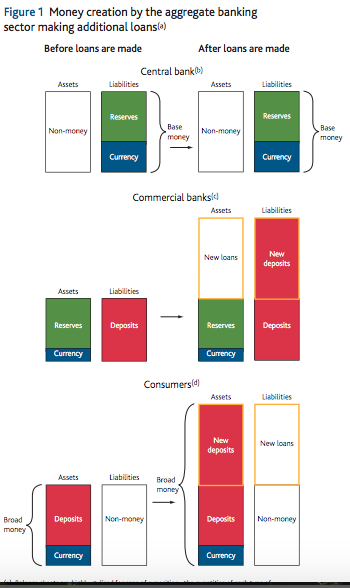

At that moment, new money is created. For this reason, some economists have referred to bank deposits as ‘fountain pen money’, created at the stroke of bankers’ pens when they approve loans. This process is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows how new lending affects the balance sheets of different sectors of the economy (similar balance sheet diagrams are introduced in ‘Money in the modern economy: an introduction’). As shown in the third row of Figure 1, the new deposits increase the assets of the consumer (here taken to represent households and companies) — the extra red bars — and the new loan increases their liabilities — the extra white bars. New broad money has been created. Similarly, both sides of the commercial banking sector’s balance sheet increase as new money and loans are created.

It is important to note that although the simplified diagram of Figure 1 shows the amount of new money created as being identical to the amount of new lending, in practice there will be several factors that may subsequently cause the amount of deposits to be different from the amount of lending. These are discussed in detail in the next section. While new broad money has been created on the consumer’s balance sheet, the first row of Figure 1 shows that this is without — in the first instance, at least — any change in the amount of central bank money or ‘base money’. As discussed earlier, the higher stock of deposits may mean that banks want, or are required, to hold more central bank money in order to meet withdrawals by the public or make payments to other banks.

And reserves are, in normal times, supplied ‘on demand’ by the Bank of England to commercial banks in exchange for other assets on their balance sheets. In no way does the aggregate quantity of reserves directly constrain the amount of bank lending or deposit creation. This description of money creation contrasts with the notion that banks can only lend out pre-existing money, outlined in the previous section. Bank deposits are simply a record of how much the bank itself owes its customers. So they are a liability of the bank, not an asset that could be lent out. A related misconception is that banks can lend out their reserves. Reserves can only be lent between banks, since consumers do not have access to reserves accounts at the Bank of England

0 Comments