Handout: Unemployment

15th September 2015

Unemployment

WHAT IS UNEMPLOYMENT?

Unemployment is a subject about which feelings run high, and it has always been a major political issue. The non‑use of land and capital carries what seems a wasteful opportunity cost but the non‑use of labour ‑ or people ‑ increases the social security burden and carries additional human costs in poverty, social decline and psychological damage. Work is a fundamental human need and for many people it is an important source of their identity and self‑respect

| The Great Depression

As the British economy followed the USA into a dramatic downward spiral, so unemployment soared. By 1932 twenty‑three per cent of the working population were without a job. In the regions of heavy industry the rate was thirty eight per cent and locally up to seventy‑five per cent. Factories closed and stood empty, ships rusted in estuaries and farmers left crops to rot in the fields. National income fell and social hardship became acute. This is the paradox of a slump. People are in great need, and wish to work. Natural and man‑made resources are ready and available. And yet nothing happens. The wheels of business simply fail to turn. The reason is lack of demand. Resources will not be employed unless there is a demand for their output at a price that sufficiently exceeds their costs. When this condition is not met, unemployment is the result. |

An increasing level of demand from the circular flow of income draws resources into employment. The higher the level of aggregate demand, the higher the proportion of the labour force that will be employed. Thus demand is the motor of employment.

In the 1960s when the economy was working at or near capacity, about 300 000 people remained unemployed. It is now clear that the current equivalent figure is around 1.6 m. If demand were to be increased. Further (e.g., in 1988 at the peak of a boom) then inflation (and the trade deficit) would rise very sharply indeed, with unacceptable consequences. The reasons for this change are complex, but possible factors include:

- employers tending to reward their permanent ‘core’ staff above the market rate to ensure loyalty and motivation. Workers out¬side the ‘core’ are employed casually or not at all

- the effective ‘dismissal’ of the long term unemployed from the labour market, so that the active labour market only operates above a certain base level of unemployment

- bottlenecks in the economy, meaning that as demand increas¬es, some industries reach full employment long before others. Rising inflation then quickly forces the government to curb demand.

- lack of training leads to inadequate skills among the workforce so discouraging investment and preventing workers from filling the vacancies that exist.

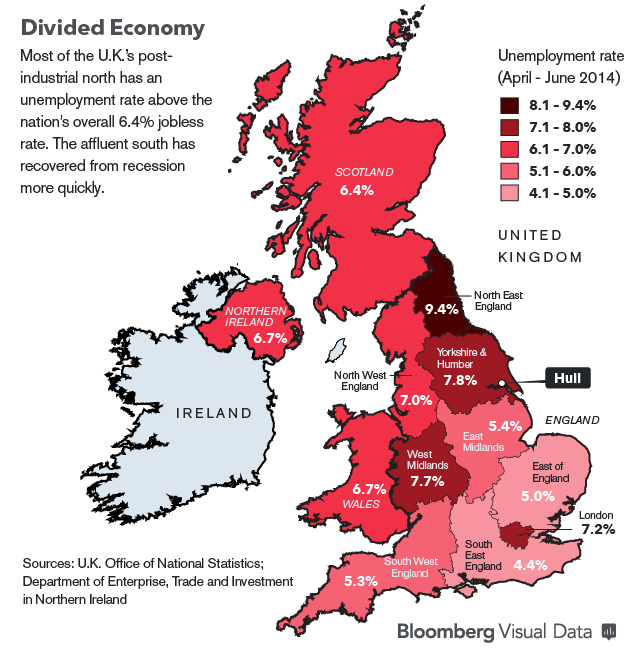

Unemployment statistics are usually presented both as a national average and on a regional basis. Regional unemployment rates are affected by:

- level of demand in specific industries

- local levels of aggregate demand

- technological developments affecting particular jobs or processes

- trade union influences

- ‘going rate’ for local wages.

Economists classify unemployment in a range of types:

- cyclical unemployment

- frictional unemployment

- structural unemployment

- regional unemployment

- technological unemployment

- seasonal unemployment

- residual unemployment

Government Policies

Measures to prevent or reduce unemployment can include:

- increased public spending

- reduce tax and interest rates

- improve training

- regional policy

- assist labour market efficiency

Effect on the Business

The level of employment directly affects all firms and has particular importance for the personnel function:

- labour turnover

- recruitment of staff

- pay and benefits

- industrial relations

- the personnel department.

Draw up a two column table. Head one column ‘high unemployment’ and the other ‘low unemployment. Use the table to summarize the situation of firms under the different circumstances.

Examine the data below and answer the question below.

Why has unemployment been persistently higher in the north west than in the South East?

Summary and comment

- before 1980 governments attempted to maintain’full employment’ by influencing the level of demand. As this proved increasingly to cause inflation, policy shifted to the ‘supply side’, with more emphasis on freer labour markets, increased training and reduced trade union power

- the rapid shrinkage of the public sector has tended to make market forces more widespread in setting employment levels

- the greatest source of new jobs is in the small firms sector, but this can be vulnerable to recession

- high regional rates of unemployment have been essentially structural as traditional heavy industries have declined. This problem may be less acute in the future, as much adjustment has now taken place

- a balanced and diversified local economy has been most effective in resisting recent rises in unemployment. An area is vulnerable when it depends heavily on one industry or one employer

- the rapid expansion of service industry in the 1980s created much new employment, but it is clear that many jobs in consumer services can disappear during an economic downturn

0 Comments