Before the financial crisis unemployment in Spain was a recurring problem. An inclination to borrow helped stimulate demand and create downward pressure on unemployment. Job creation was also helped by a sustained construction boom. Unemployment in 2007 was just 8%. The rate unemployment rate remains stubbornly above 20%.

Across Europe it is young people who have been badly hit by the economic downturn. The number of 15-24 year olds who are underemployed in the OECD is higher than at any time since the organisation began collecting data in 1976.

Youth unemployment has not been helped by poor growth and the adoption of austerity programmes by major industrial nations. Many European countries have also cut back on stimulus measures intended to create a job stimulus increasing the possibility of unemployment rates rising across Europe.

In the past, young jobless have often been the first to lose their jobs but some of the first to secure employment as economies recover. However, this business cycle has seen a sluggish recovery and job creation has been sluggish. Analysts argue that in some countries there has been a rigging of the labour market in favour of those in work and against young job seekers.

Youth unemployment in Spain currently stands at 55%. This unemployment rate is the second highest rate in the European Union. Only Greece has a higher rate of youth unemployment rate. One quarter of all Spaniards aged between 18 and 29 is a NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training). This is one of the highest rates in the developed world. In all, 1.7 million Spaniards under the age of 30 are unemployed. Nearly 900,000 of those out of work are already classed as long-term unemployed.

There is little chance of these unemployment figures improving dramatically in the short-term. The Spanish economy is no longer in recession and the number of unemployed has fallen from an all-time high in 2013. Graduates who have completed their University course over the last few years face an uncertain future. Jobs for newly qualified graduates remain in short supply. This group are likely to experience what economists refer to as ‘scarring.’ Scarring occurs when young workers fail to find work early on and even if they do find work eventually and join the labour market, they will never catch up with the earnings and career prospects that they might have achieved.

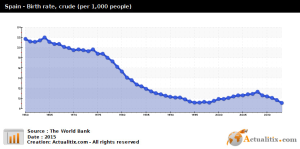

There are other costs associated with youth unemployment is Spain, apart from no money and no career. The youth in Spain are effectively barred from the housing market and are consigned to living with family members. The long term implication for Spain is a demographic dip. If young people cannot find a job and cannot afford a home of their own, then they are likely to delay starting a family. The difficult financial circumstances mean that the youth of Spain are likely to be consigned to long term financial dependence on their families and a deep sense of financial insecurity.

Young and unemployed

Half of all young spaniards under the age of 30 are living at home with their parents. Those who have paid into the social security system may receive a few hundred euros in unemployment benefits. Most survive on handouts from their parents, effectively having to subsist on pocket money. If they are really lucky they may be able to obtain part-time or temporary work in bars or other low paid service sector jobs.

Graduates have found it extremely difficult to find employment. A 26 year old who spent five years training to be a nurse has never had a job in the career she trained for. Since completing her degree she has had to make do with part time temporary jobs. Of the 100 trainee nurses who trained with her only two have found employment as nurses.

Youth unemployment brings with it direct costs. Benefit payments are increased. Unemployment means lost tax revenues and wasted productive capacity.

The indirect costs of unemployment include emigration. The most ambitious and well qualified young people may well look abroad for improved employment opportunities. Young people are more likely to emigrate than older workers with dependents. Another indirect cost of youth unemployment is a higher incidence of crime. Researchers have identified a causal link between youth unemployment and higher rates of crime, including robbery, car theft, burglary, drug offences and criminal damage to property.